Abstract

Background: With federal abortion protections under threat, it is important to consider how abortion care access will change in certain places and populations if abortion laws revert to states. Abortion policy and access have strong spatial patterns in the US. State-level bans could severely reduce access in vast regions, worsening access in areas with already poor access. This may exacerbate disparities and lead to large-scale impacts on reproductive health. Beyond describing where abortion care may change, we sought to describe which populations could experience the most dramatic impacts if state-level bans are enacted.

Methods: We conducted an ecological and spatial analysisof abortion facilities and county-level populations in the contiguous United States (CONUS). Outcomes were Euclidean distance to abortion care, as well as change in distance after policy changes.

Findings: If states enact abortion bans as expected, 46.7% of the country’s women would see an increase in distance to abortion care. Currently, more than half (62.6%) of all U.S. women live within 10 miles of an abortion clinic, but if state-level abortion bans go into effect, only 40.2% of women would live that close. The median distance would increase from 38.9 miles to 113.5 miles. In particular, women in the Deep South, Midwest, and Intermountain West could have to travel much farther for care. State-level bans may disproportionately impact women of color, those living in poverty, and people with less education.

Interpretation: The impacts of state-level abortion bans will span across racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic demographics, but the effects will be felt disproportionately by Black, Hispanic/Latinx, and impoverished women and those with less education. The changes have potential to exacerbate disparities in maternal healthcare outcomes at a large scale.

Funding: We have no funding sources to disclose.

Introduction

As abortion-restricting legislation has been enacted at the state level, spatial disparities in abortion care access have grown1 — and with the Supreme Court’s expected majority ruling to strike down Roe v. Wade, access to abortion care will likely become substantially worse in large regions of the country.

In the decades since the Roe v. Wade decision, abortion has been the target of numerous legal restrictions.2 By mid-year, 2021 was already the most prolific year for abortion legislation, with 21 state governments enacting restrictive abortion laws.3 In the most extreme case, the Texas legislature prohibited abortion beyond six weeks of gestation with Senate Bill 8 (SB 8), effectively banning most abortions; healthcare providers estimated that 85 to 90% of patients seeking an abortion in Texas were beyond the six-week mark.4

On December 1, 2021, the Supreme Court heard arguments in the case of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, in which the state of Mississippi has asked the court to reverse all prior abortion decisions. This would remove federal protections of the right to abortion before fetal viability, allowing states to establish laws that could restrict abortion completely. While a formal decision is not expected until June 2022, the majority of justices are in favor of reversing or weakening Roe v. Wade.5,6

When abortion access is restricted, women seeking an abortion experience more stress, incur more out-of-pocket expenses, and must travel farther to obtain care.7 Restricting access to abortion services is also associated with adverse maternal and infant health outcomes.7–9 When restrictive legislation was enacted at the state-level in Texas, women of color were disproportionately affected. Average abortion rates progressively decreased as distance to clinics increased, but women of color were less likely to successfully obtain an abortion than White women.10 While disparities in abortion care have previously been documented, the scale and degree of impact on sociodemographic groups with state bans has not been investigated in a published study.11 Herein we quantify how distance to abortion care is expected to change in the US without Roe v. Wade.

Methods

A list of 1,045 abortion clinics was obtained from the Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health (ANSIRH) group’s Abortion Facilities Database. ANSIRH is based at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), and the database is updated periodically. Clinics that have closed (N = 238) or do not provide abortion services (N = 294) were excluded, leaving a total of 739 clinics for analysis.

County-level characteristics were obtained for women aged 15–49 in 3,108 counties in the contiguous US, and these attributes were applied to the county population-weighted centroids. We examined differences in expected increase in distance to care by race (Black, White, American Indian, Asian, Pacific Islander, Multiple Races), ethnicity (Hispanic or Latinx, not Hispanic or Latinx), educational attainment (some high school, high school diploma, some college, college degree), poverty, and rurality. Racial and ethnic composition and population estimates for 2019 were obtained from the US Census Bureau (USCB).12 Poverty, education, and rurality measures were obtained from the USDA Economic Rural Development Society (ERDS), which were based on the 2020 Census and 2015-2019 American Community Survey (ACS).13,14 Of note, ACS measures of educational attainment only describe individuals aged 25 or older.

Twenty-one states have legislation in place that would almost certainly ban abortion if Roe v. Wade were overturned or weakened, and five additional states would be likely to ban abortion without federal protections in place.15 These include most Southern states (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, West Virginia), areas of the Midwest (Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, Wisconsin) and parts of the West (Arizona, Idaho, Montana, Utah, Wyoming).15

Change in distance to abortion clinics was out primary outcome, with a secondary outcome of the amount of change in distance. Using ArcGIS Pro software from the Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI), Euclidean distance to the nearest abortion clinic was calculated in miles for all county centroids.16,17 Clinics in states likely to ban abortion were then removed, and the Euclidean distance was re-calculated. If distance to abortion care increased, that county population was considered to be affected by potential abortion bans. These geographic measures were merged with sociodemographic variables, and the resulting data were analyzed further in R statistical software. Counties were grouped by expected increase in distance to abortion care (no change, ≤50 miles, ≤100 miles, ≤150 miles, ≤300 miles, ≤400 miles, and >400 miles). Distance increments were chosen for interpretability and visualization, with larger increments at greater distances.

Results

More than half (62.6%) of all U.S. women currently live within 10 miles of an abortion clinic, but if state-level abortion bans go into effect, only 39.0 percent of women would live that close. Most counties (N = 1694, 62.0%) would experience an increase in distance to abortion clinics. The median distance to the nearest clinic is currently 38.9 miles, but with bans the typical distance would increase almost three-fold (median: 113.0 miles).

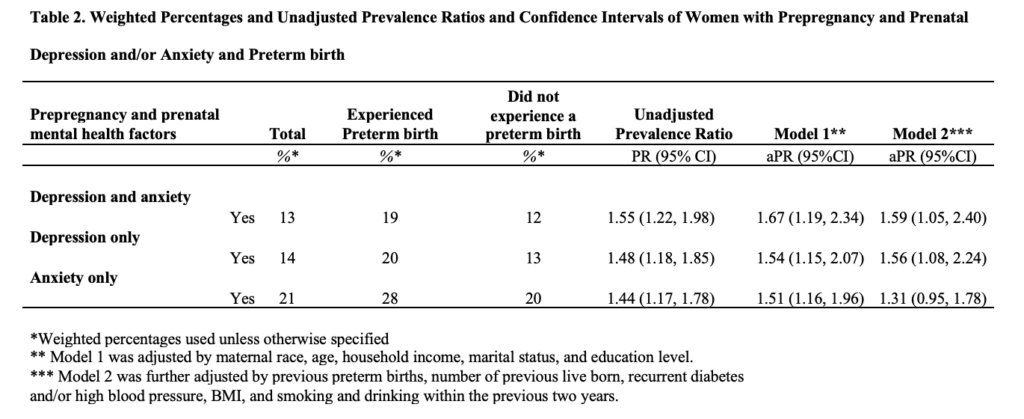

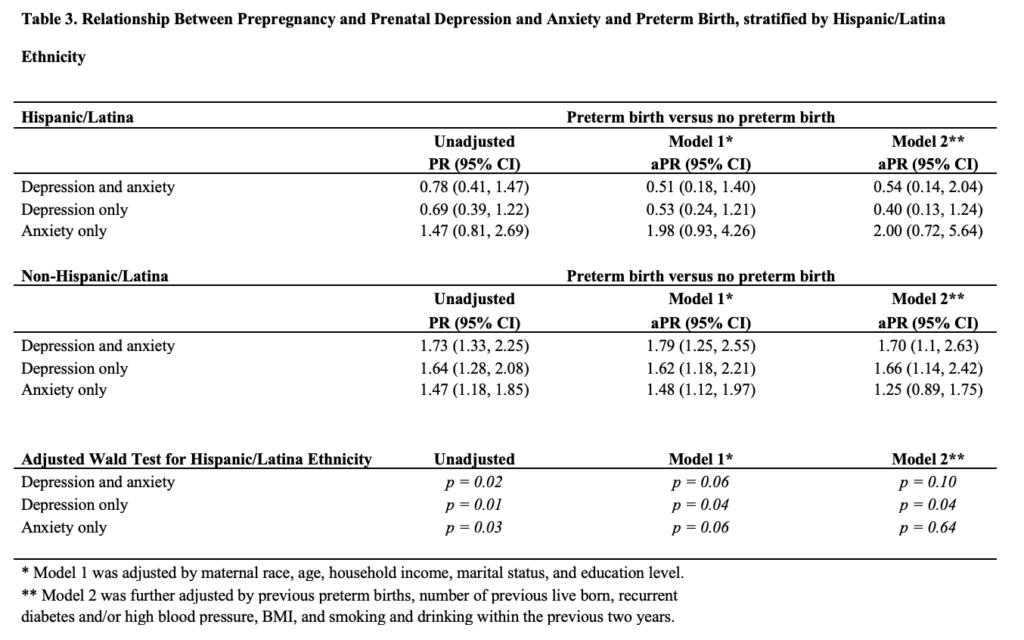

With state-level abortion bans, about 50 million women aged 15–49 (59.5% of this population) would live in counties without a clinic — 1.7-times more than present. As Figure 1 shows, wide swathes of the country would have to travel hundreds of miles for care, including most of the South, portions of the Midwest, and throughout the Intermountain West. Figure 2 illustrates where the change would have the most pronounced impact, with county populations experiencing the greatest change in distance to care. In the top map of Figure 2, dark red areas represent counties with an increase of greater than 100-fold. These are primarily urban counties containing abortion clinics, and populations in these areas would experience the most dramatic impacts. For instance, a typical person in Miami-Dade County, Florida currently needs to travel less than a mile for care — but that distance would increase by 426 miles. The lower map in Figure 2 shows this change in distance in terms of miles. Distance to care would increase by hundreds of miles for the Deep South, with no bordering states providing care. Table 1 shows county-level sociodemographic characteristics by expected change in distance (no change, ≤50 mi, ≤100 mi, ≤150 mi, ≤300 mi, ≤400 mi, >400 mi).

Both rural and urban areas will be impacted if state-level bans are implemented. About 59% of rural counties (N = 1,077) and 66% of urban counties (N = 865) will be affected. Of Both rural and urban areas will be impacted if state-level bans are implemented. About 66% of rural counties (N = 680) and 60% of urban counties (N = 1,014) will be affected. Of the 46 counties that will see an increase of more than 400 miles, 89.1% are also urban. As shown in Figure 2, the relative change in distance to care would increase most dramatically in urban areas, where most clinics are currently located.11 More than 36 million women in urban areas will be impacted to some degree. Relatively small changes (increases of less than 50 miles) will be experienced by more rural areas (56.9%), because most clinics are further from rural populations. Across all groups, 68.7% of women of reproductive age in rural populations would see an increase in distance required to reach an abortion clinic.

Economic measures tend to change as distance to care increases. The most affluent group, with the highest median household income at $60,724, will experience no change in distance to care. Poverty levels (11.1%) are also lowest in this group and highest (14.0%) in the next group, which will experience the smallest impacts (change of ≤50 mi). In unaffected areas, a college degree is the most common educational attainment (24%). In places with relatively minor impacts (change of ≤50 mi), a high school diploma is more common than a college degree (21.9% vs. 16.3%). Areas with the biggest impacts (change of >400 miles) also have the highest proportion of people without a high school diploma at 10.9% and the highest poverty rate (14.9%).

Proportions of Asian people and those of two or more races were highest in areas with no change. In these counties, 12.0% of people are Black. By contrast, counties with the biggest expected impacts are 18.5% Black. This group also has the lowest proportion of White people at 74.3%, although 45.0% of the people in these areas are also Hispanic or Latinx. This area, visualized in the absolute change map of Figure 2, consists of most of the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, encompassing large regions of Texas and Florida, most of Louisiana, and areas of Mississippi and Alabama. It also includes one county in Montana.

About 45 million women of reproductive age (53.5%) will experience no change in distance to abortion care. Roughly 16 million (19.3%) may have to travel up to 150 miles further than they do currently. Combined, 24 million women (29.3%) will see an increase in travel distance greater than 150 miles to obtain care.

It is important to note that, while the degree and relative amount of impact varies across demographic groups, all sociodemographic groups would, on average, see an increase in distance to abortion care on average.

Discussion

Millions of women would be affected by state-level abortion restrictions, and racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in distance to care would be exacerbated. These results represent the worse-case scenario, assuming Roe v. Wade is overturned all 26 states restrict abortion to the point that all clinics close. However, because 12 states (including Utah) have “trigger” bans3 — set to take effect immediately if Roe v. Wade is overturned — some of these impacts are guaranteed to take effect, if the Supreme Court rules in favor of Mississippi.

While distance to abortion care will increase dramatically in some areas, access will be more difficult for some than others. Women with resources enabling them to travel will likely be more successful in obtaining an abortion. However, our results show that distance to abortion care would increase the most for counties whose populations are already the most disadvantaged. This could exacerbate existing healthcare disparities, both geospatial and sociodemographic.19

Across all distance to care, there will be urban and rural populations. Rural areas, which already have disparate access to healthcare, will be positioned even further from abortion care. Some urban areas, despite having concentrated populations and greater demand for health services, would become deserts for abortion care, as shown in Figure 1. Salt Lake City, Utah, for example, has the nearest abortion clinic to some parts of Wyoming, Idaho, and Nevada. Without it, even Salt Lake City residents would need to travel hundreds of miles to reach the nearest clinic, in Colorado. Changes like this could create a complex issue of managing reproductive care for a variety of geographically diverse populations, and meeting this need will likely require a multi-pronged approach.

Given the magnitude of state-level bans, we expect to see a variety of large-scale impacts from state-level bans, particularly if these policies do not increase contraceptive access. Unfortunately, some women will likely be desperate enough to resort to unsafe methods for terminating their pregnancy.8 Poor access to abortion care is associated with poor maternal and infant health, and many groups may experience increases in these impacts.9 With millions more women living farther from care, the clinics that remain open will likely experience higher patient volume. After restrictions were imposed in Texas in 2020, the number of out-of-state abortions increased by more than 600%.20

In some ways, the Supreme Court’s decision could set women’s health back decades — however, America today is not the same as pre-Roe America. Women can easily learn about their options online. They can find providers, connect with advocates, and learn about the dangers of attempting to end their pregnancy without a medical professional. As always with the internet, misinformation will likely spread as well.

Limitations

Because we used areal units, this study is subject to ecological bias. The ability to obtain an abortion likely varies within counties, and beyond this, people with financial means can travel farther distances for care. Furthermore, the demographic composition of counties does not perfectly reflect the populations seeking an abortion.

We used Euclidean distance to approximate travel distance. Calculating Euclidean distance with population-weighted centroids tends to underestimate driving distance to healthcare facilities in both rural and urban areas.19 However, not all women have access to a vehicle, and in regions where women may need to travel hundreds of miles for care, those with financial means may choose to travel by airplane. Because Euclidean distance performs equally well for rural and urban areas and does not assume mode of travel, we preferred this method.

Medication abortions are becoming more widely available, although these may be targeted by state-level policies, as well. These may be sought online, preventing travel, but it will be difficult to predict the scale of medication abortions, particularly when obtained illegally.

The disparities described here only reflect the disparities in distance to care — but this will likely compound with other disparities. As this study was conducted at the county level, we were not able to parse out the intersectionality of these issues, although it is worthy of further investigation.

Conclusion

Millions of women will be impacted if Roe v. Wade is overturned or weakened. State-level abortion bans may exacerbate racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities. Healthcare professionals and patient advocates should prepare to address these disparities and provide for patients as abortion care dynamics evolve.

Acknowledgments

We thank Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health (ANSIRH), University of California, San Francisco, for providing abortion facility data.

Funding: The authors have no conflicts of interest or funding sources to declare.

Data Sharing: County-level data and a data dictionary will be made available to others upon publication (brenna.kelly@hsc.utah.edu). In accordance with ANSIRH’s Abortion Facilities Database Confidentiality Agreement, facility data and identifying information cannot be disclosed.

References

- Policy Surveillance Program. State abortion laws. Updated March 1, 2022. Accessed March 23, 2022. https://lawatlas.org/datasets/abortion-laws

- Berer M. Abortion law and policy around the world: In search of decriminalization. Health and Human Rights 2017; 19.

- Nash E, Guttmacher Institute, Cross L. 26 states are certain or likely to ban abortion without Roe: Here’s which ones and why. Guttmacher Institute. 2021; published online Oct 26.

- White K, Vizcarra E, Palomares L, et al. Initial Impacts of Texas’ Senate Bill 8 on Abortions in Texas and at Out-of-State Facilities. Austin, TX, 2021.

- Totenberg N. Roe v. Wade’s future is in doubt after historic arguments at Supreme Court. National Public Radio. 2021; published online Dec 1.

- Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. Supreme Court of the United States, No. 19-1392 (draft, circulated Feb 10, 2022) Accessed May 3, 2022. https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/21835435/scotus-initial-draft.pdf

- Gerdts C, Fuentes L, Grossman D, et al. Impact of clinic closures on women obtaining abortion services after implementation of a restrictive law in Texas. American Journal of Public Health 2016; 106. DOI:10.2105/AJPH.2016.303134.

- Harris LH, Grossman D. Complications of Unsafe and Self-Managed Abortion. New England Journal of Medicine 2020; 382. DOI:10.1056/nejmra1908412.

- Pabayo R, Ehntholt A, Cook DM, Reynolds M, Muennig P, Liu SY. Laws restricting access to abortion services and infant mortality risk in the United States. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020; 17. DOI:10.3390/ijerph17113773.

- Goyal V, Brooks IHML, Powers DA. Differences in abortion rates by race–ethnicity after implementation of a restrictive Texas law. Contraception 2020; 102. DOI:10.1016/j.contraception.2020.04.008.

- Bearak JM, Burke KL, Jones RK. Disparities and change over time in distance women would need to travel to have an abortion in the USA: a spatial analysis. The Lancet Public Health 2017; 2. DOI:10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30158-5.

- US Census Bureau. 2010-2019 Annual County Resident Population Estimates by Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-counties-detail.html 2020. (Accessed Dec 15, 2021)

- Economic Research Service. Poverty estimates for the U.S., States, and counties, 2019. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/county-level-data-sets/ 2019. (Accessed Dec 10, 2021)

- Economic Research Service. Educational attainment for the U.S., States, and counties, 1970-2019. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/county-level-data-sets/ 2019. (Accessed Dec 10, 2021)

- Nash E, Guttmacher Institute, Naide S. State policy trends at Midyear 2021: Already the worst legislative year ever for U.S. abortion rights. Guttmacher Institute. 2021; published online Oct 28.

- ESRI. ESRI ArcGIS Pro. Redlands, CA, USA. 2021.

- US Census Bureau. Centers of population. https://www.census.gov/geographies/reference-files/time-series/geo/centers-population.html 2020. (Accessed Dec 1, 2021)

- Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing v. 3.6. 1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2019). Scientific Reports 2021; 11.

- Wakefield D v., Carnell M, Dove APH, et al. Location as Destiny: Identifying Geospatial Disparities in Radiation Treatment Interruption by Neighborhood, Race, and Insurance. International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics 2020; 107. DOI:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.03.016.

- White K, Kumar B, Goyal V, Wallace R, Roberts SCM, Grossman D. Changes in abortion in Texas following an executive order ban during the coronavirus pandemic. JAMA – Journal of the American Medical Association. 2021; 325. DOI:10.1001/jama.2020.24096.

Citation

Kelly BC, Brewer SC, Hanson HA. (2022). Disparities in Distance to Abortion Care Under Reversal of Roe v. Wade. Utah Women’s Health Review. doi: 10.26054/0d-4zt7-ts67