Background

Approximately 700 women die each year from pregnancy-related complications in the United States. About one in three maternal deaths happen between one week and one year postpartum. Most of these deaths are preventable, and closing the gaps in access to quality care can help.1 Postpartum healthcare occurs during the first six weeks after childbirth and examines various aspects of maternal health, including physical, mental, and emotional.2 Many women experience various physical discomforts, including increased rates of fatigue,3 increased backaches and headaches,4 sleep disorders, and bowel disorders.3 Becoming a mother can sometimes provoke mental and emotional distress, often becoming too severe and resulting in postpartum depression.5 The lack of postpartum follow-up can sometimes leave many diseases undiagnosed, often leading to postpartum death. Postpartum death can also occur due to severe bleeding, high blood pressure, infection, and cardiomyopathy.

Postpartum visits allow healthcare providers to screen for maternal emotional health, facilitate breastfeeding, monitor the newborn’s growth and overall health, counsel women about family planning, and refer mother and baby to additional services.6 These visits become critical in maintaining maternal and neonatal health. This review aims to assess the prevalence of postpartum care and identify the demographics of the women who miss their postpartum checkups in Utah.

Methods

We used 2012-2020 data for women for the Utah Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) via the IBIS-PH interactive query system to investigate postpartum care in Utah. PRAMS is an ongoing, population-based surveillance project coordinated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Utah is one of 47 states that collect PRAMS data annually with the intent to monitor maternal and child health indicators. Each month, approximately 200 new mothers are randomly selected for participation using Utah birth certificates. Data is collected by following a protocol developed by the CDC that utilizes mail and telephone questionnaires, and approximately 60% of randomly-selected new mothers respond to the surveys. The responses are weighted to represent all women who have live births in Utah.7

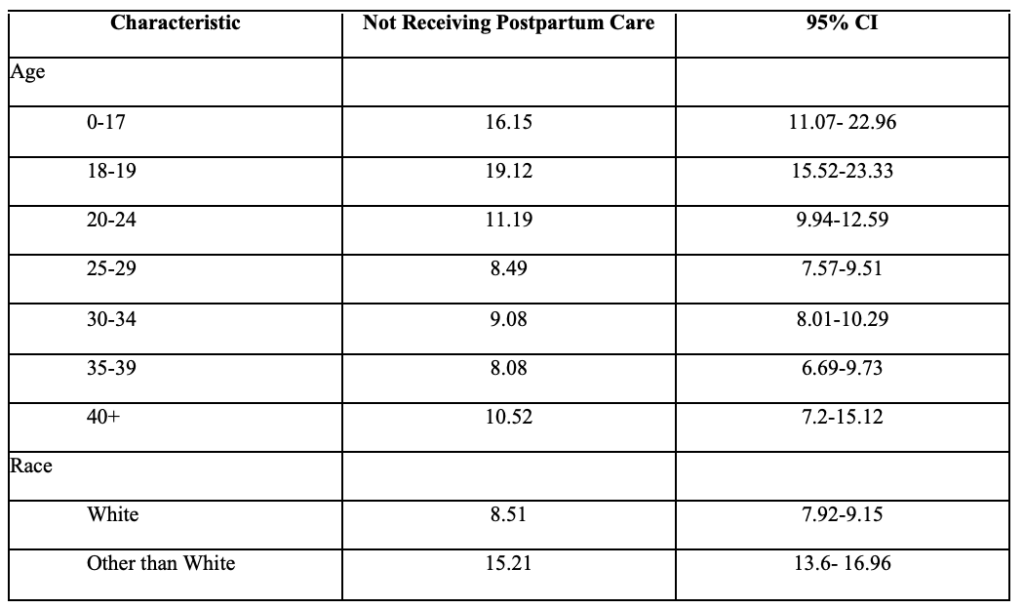

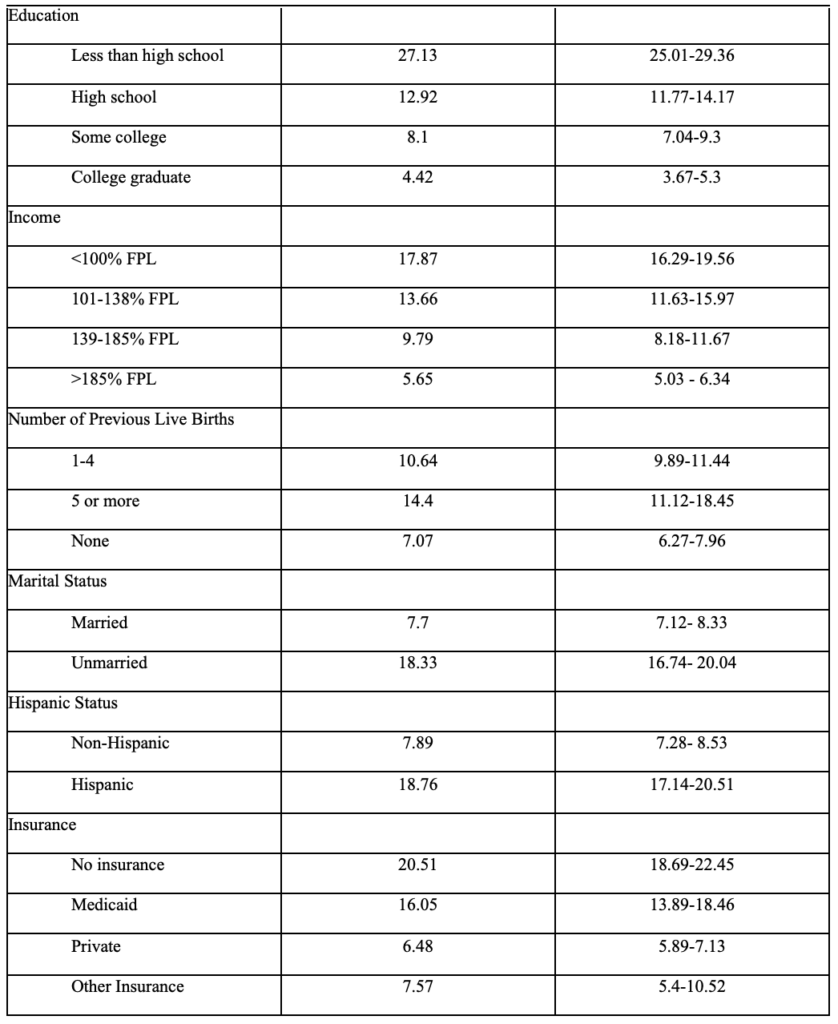

Missed postpartum appointments served as the outcome of interest. This outcome was assessed via the question, “Since your new baby was born, have you had a postpartum checkup for yourself?” The response to this question was binary (yes/no). The demographics available to us through the PRAMS data were age, race, education, income, previous live births, marital status, ethnicity, and insurance status. Age was separated into 7 different categories: 0-17, 18-19, 20-24, 25-29, 30-34, 35-39, 40+). Parity was divided into three categories: no prior live births, 1-4 prior live births, and 5+ live births. Race was dichotomized into White and non-White participants, and education was divided into less than high school, high school, some college, or college graduate. Prevalence of missed checkups and 95% confidence intervals were reported. The data reported through IBIS-PH considered weighted stratified sampling used by PRAMS.

Results

12,814 women, with a yearly range of 1,232 to 1,698, participated in UT-PRAMS from 2012 to 2020. Out of these women, in 2020, 11.14% (CI 9.4 -13.16%) of women did not attend their postpartum checkups. The rate of women without a postpartum check had declined steadily from 10.22% in 2014 to 7.97% in 2019. The 2020 rate of 11.14% is the highest recorded (Table 1).

Figure 1 shows the prevalence of not receiving postpartum care among non-White women in Utah is much higher than White women. It ranges from 9.65% in 2016 (CI 5.1% – 15.4%) to 21.19% in 2014 (16.11% – 27.35) of women identifying as non-White not receiving postpartum care. In 2020, 9.78% of White mothers (CI 8.0 – 11.9%) did not have a postpartum checkup compared to 19.04% of non-White mothers (CI 13.52 – 26.14%).

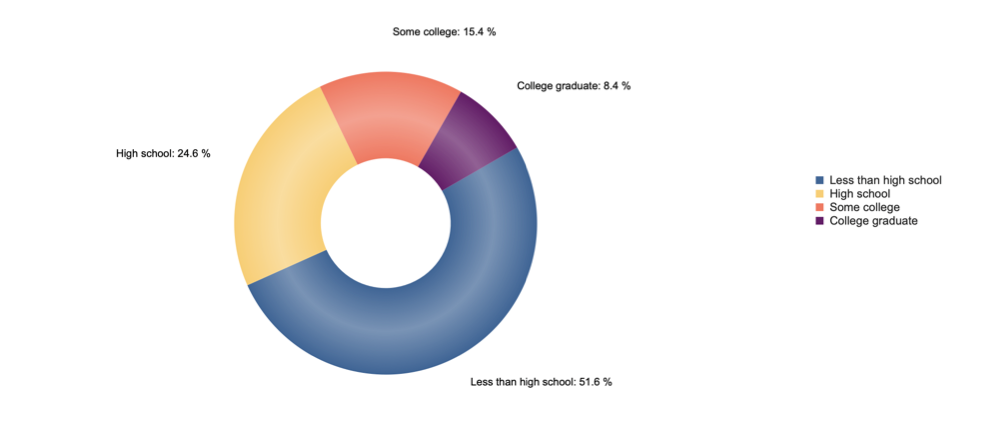

Women who did not receive postpartum care tended to have lower education levels (Figure 3). Between 2012 and 2020, women with less than a high school education contributed to 51.6% of those who did not receive postpartum care. In 2020, 34.03% of mothers with less than high school education, 13.8% with high school education, 10.92% with some college, and 5.55% with college degrees did not have a postpartum visit. Table 2 shows the prevalence of missed postpartum checkups based on the demographics provided by IBIS-PH.

Conclusion

The data snapshot of Utah PRAMS from 2012-2020 reveals increases in postpartum care for multiple demographic categories between 2012 and 2019 until a decrease in 2020. In general, women who did not receive postpartum care were younger, less educated, unmarried, underinsured, lower-income, and have more children than women who receive postpartum care. This review examined the demographics of women who were more likely to miss a postpartum checkup. Determining these demographics can help target future interventions to increase postpartum care. The social determinants of health, such as age, race, insurance type, education, and income, play a significant role in whether a woman will attend her postpartum checkup, as previous studies have shown.8, 9 Postpartum care touches on all seven health domains while emphasizing physical, social, and emotional health.

Women under 20 years old were less likely to attend postpartum checkups, as shown in our data snapshot and other studies.10 Wilcox et al. suggests that rates of postpartum depression are higher among adolescents.8 Still, because these women are more likely to miss their checkups, providers are less likely to identify and treat the symptoms. Others mention that postpartum depression does not occur immediately after discharge, so rapid screening becomes ineffective and long-term postpartum care is necessary.11 Sober et al. examined adolescent pregnancies and found that two-thirds of the teens felt they became pregnant ‘too soon.’12 Creating programs emphasizing family planning and contraceptive usage can help delay unwanted childbearing in adolescents.

Barriers to postpartum-care access play a role in postpartum checkup appearances. Women with Medicaid or without insurance, and those who live below the federal poverty level, are less likely to attend postpartum checkups. Currently, Utah Medicaid participants only have up to 60 days of postpartum coverage, which would not be sufficient to be able to diagnose and treat particular mental, physical, or emotional distresses.13 Our findings correspond with national data on other states that have not approved Medicaid expansion. These individuals are less likely to gain access to a provider, or paying for a checkup may be a low priority.14 Mothers may prioritize purchasing essentials for their infants instead of postpartum healthcare. States with Medicaid expansion had increased usage of postpartum services, such as preventive, contraceptive, and mental health services.15, 16 Policy changes that include more women covered by governmental healthcare assistance can help increase postpartum checkup attendance.

Policy Implementations and Interventions

Federal legislation serves as the primary catalyst for improved maternal health outcomes, including postpartum checkup attendance.17 One legislative change would be to include state Medicaid coverage of birth center deliveries, as only 30 state Medicaid programs cover these costs.18, 19 Strengthening these birth centers can improve access to maternal care for low-income women and ease the burden on hospital systems. Changing economic incentives, such as lowering the reimbursement for unnecessary cesarean sections and increasing midwives’ compensation, can also improve maternal health outcomes. Financial adjustments can also include increasing coverage for home births and lactation consultants.20, 21

Community interventions play an equally important function in improving postpartum checkup attendance. Establishing bilingual partners and doula programs have improved postpartum care rates and the quality of care.22, 23 These programs target minority, low-income groups to receive quality care. Other interventions include providing postpartum care information packets and lists of community resources to pregnant women; studies conducted by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services found that 100 percent of women who received these packets attended their postpartum care appointments.23 Some women do not attend postpartum appointments due to further barriers, such as lack of transportation. To combat these barriers, healthcare teams could make home visits to screen for postpartum depression, educate the mothers, and conduct a postpartum assessment.23, 24

Limitations

The standardized approach of PRAMS’ data comparison across multiple states and years increases the breadth and depth of the data collected. Information is collected on demographics, preconception, pregnancy, and postpartum on health-related behaviors, attitudes, and outcomes. However, limitations of our study also arise from the data collected through PRAMS. PRAMS data are self-reported and may be subject to social desirability and recall biases. Additionally, some of the variables are limited in the data they report. For example, parity is only defined as no live births, 1-4 live births, or 5+ live births. PRAMS also lacks information about pregnancy complications and delivery type, which may play a significant role in care. There are other factors that PRAMS does not address, like available transportation to the doctor and distance to a healthcare facility.

Conclusion

In this data snapshot, sociodemographic factors were highly associated with missing a postpartum checkup. Because these checkups help examine women’s mental and physical health, interventions focused on improving attendance of postpartum checkups can substantially increase the health of new mothers and neonates. Finding new ways to create accessible and affordable healthcare can also increase the attendance of these appointments. Interventions that educate the public, especially underserved populations, about the necessities of postpartum care could also improve attendance.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy-related deaths. Accessed March 17, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/maternal-deaths/index.html

2. Polk S, Edwardson J, Lawson S, et al. Bridging the Postpartum Gap: A Randomized Controlled Trial to Improve Postpartum Visit Attendance Among Low-Income Women with Limited English Proficiency. Womens Health Rep (New Rochelle). 2021;2(1):381-388. doi:10.1089/whr.2020.0123

3. Ansara D, Cohen MM, Gallop R, Kung R, Schei B. Predictors of women’s physical health problems after childbirth. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. Jun 2005;26(2):115-25. doi:10.1080/01443610400023064

4. Saurel-Cubizolles MJ, Romito P, Lelong N, Ancel PY. Women’s health after childbirth: a longitudinal study in France and Italy. Bjog. Oct 2000;107(10):1202-9. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb11608.x

5. Cheng CY, Fowles ER, Walker LO. Continuing education module: postpartum maternal health care in the United States: a critical review. J Perinat Educ. Summer 2006;15(3):34-42. doi:10.1624/105812406×119002

6. Maternal Health Task Force. Postnatal Care. Accessed March 15, 2022. https://www.mhtf.org/topics/postnatal-care/

7. PRAMS U. Maternal and Infant Health Program. Accessed 2022, March 15. https://mihp.utah.gov/pregnancy-and-risk-assessment

8. Wilcox A, Levi EE, Garrett JM. Predictors of Non-Attendance to the Postpartum Follow-up Visit. Matern Child Health J. Nov 2016;20(Suppl 1):22-27. doi:10.1007/s10995-016-2184-9

9. Henderson V, Stumbras K, Caskey R, Haider S, Rankin K, Handler A. Understanding Factors Associated with Postpartum Visit Attendance and Contraception Choices: Listening to Low-Income Postpartum Women and Health Care Providers. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2016/11/01 2016;20(1):132-143. doi:10.1007/s10995-016-2044-7

10. Nunes AP, Phipps MG. Postpartum Depression in Adolescent and Adult Mothers: Comparing Prenatal Risk Factors and Predictive Models. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2013/08/01 2013;17(6):1071-1079. doi:10.1007/s10995-012-1089-5

11. Sit DK, Wisner KL. Identification of postpartum depression. Clin Obstet Gynecol. Sep 2009;52(3):456-68. doi:10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181b5a57c

12. Sober S, Shea JA, Shaber AG, Whittaker PG, Schreiber CA. Postpartum adolescents’ contraceptive counselling preferences. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. Apr 2017;22(2):83-87. doi:10.1080/13625187.2016.1269161

13. Eckert E. Preserving the Momentum to Extend Postpartum Medicaid Coverage. Womens Health Issues. Nov-Dec 2020;30(6):401-404. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2020.07.006

14. Johnston EM, McMorrow S, Caraveo CA, Dubay L. Post-ACA, More Than One-Third Of Women With Prenatal Medicaid Remained Uninsured Before Or After Pregnancy. Health Affairs. 2021;40(4):571-578. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01678

15. Wang X, Pengetnze YM, Eckert E, Keever G, Chowdhry V. Extending Postpartum Medicaid Beyond 60 Days Improves Care Access and Uncovers Unmet Needs in a Texas Medicaid Health Maintenance Organization. Brief Research Report. Frontiers in Public Health. 2022-May-03 2022;10doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.841832

16. Kumar N, Quinlan M. Making the Case for Expanding Medicaid Coverage to 12 Months Postpartum [23M]. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2020;135:140S-141S. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000664800.77848.f9

17. Khanal P, McGinnis T, Zephyrin L. Tracking State Policies to Improve Maternal Health Outcomes. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2020/tracking-state-policies-improve-maternal-health-outcomes

18. Ranji U, Salganicoff A, Stewart AM, Cox MA, Doamekpor L. State Medicaid coverage of perinatal services: Summary of state survey findings. 2009;

19. Howell E, Palmer A, Benatar S, Garrett B. Potential Medicaid cost savings from maternity care based at a freestanding birth center. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2014;4(3)doi:10.5600/mmrr.004.03.a06

20. Courtot B, Hill I, Cross-Barnet C, Markell J. Midwifery and Birth Centers Under State Medicaid Programs: Current Limits to Beneficiary Access to a High-Value Model of Care. Milbank Q. Dec 2020;98(4):1091-1113. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.12473

21. Hill I, Benatar S, Courtot B, et al. Strong Start for Mothers and Newborns Evaluation. 2016

22. Marsiglia FF, Bermudez-Parsai M, Coonrod D. Familias Sanas: an intervention designed to increase rates of postpartum visits among Latinas. J Health Care Poor Underserved. Aug 2010;21(3 Suppl):119-31. doi:10.1353/hpu.0.0355

23. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Resources on Strategies to Improve Postpartum Care Among Medicaid and CHIP Populations. 2015.

24. Tabb KM, Bentley B, Pineros Leano M, et al. Home Visiting as an Equitable Intervention for Perinatal Depression: A Scoping Review. Review. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2022-March-18 2022;13doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.826673

Citation

Shaaban M, Turner E, & Myrer R. (2022). Postpartum Checkups in Utah: An Analysis of 2012-2020 Utah Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) Data. Utah Women’s Health Review. doi: 10.26054/0d-38dn-fjaf