The emotional health and wellness needs of women vary throughout their lifespan. Symptoms related to and diagnoses of anxiety and depression are core components of mental health. In this article, we will focus on anxiety and depression among women during adolescence, the childbearing and reproductive years, and the perimenopausal, menopausal and postmenopausal period. Understanding how the presentation of anxiety and depression can differ throughout a women’s life is critical for directing women and their providers to evidence-based resources and treatment options necessary for minimizing burden and stigma and maximizing mental health.

Children and Adolescents

Introduction

Child and adolescent mental health refers to children and adolescents’ emotional, psychological, and social well-being. It encompasses many factors contributing to a child’s overall mental state and behavior, including emotions, thoughts, and interactions with others. Childhood and adolescence are critical times for rapid brain development and also involve various factors that can influence a child’s mental health, such as genetic predispositions, in-utero exposures, family dynamics, societal influences, traumatic experiences, and environmental stresses. These developmental stages provide critical periods for prevention, early detection, and intervention.

A landmark study documented the profound impact of adverse childhood experiences on later adult health outcomes1, and subsequent research has clarified that this lifelong effect is due to significant changes in the nervous, endocrine, and immune systems from prolonged exposure to the stress response2. In short, health across the lifespan is impacted by early childhood experiences.

Depression & Anxiety

As we consider depression in biological females, it is essential to consider the prevalence and timeline of depression in children and adolescents. In childhood, the diagnosis of depressive disorder is uncommon in both genders (estimated to be between 0.5% and 2.5%)3. Comparatively, depression and anxiety prevalence rates increase significantly in adolescents with lifetime prevalence of these conditions through adolescence estimated to be 15.9% and 38%, respectively.4 The incidence of new female cases of depression is approximately twice that of males during adolescence.5

Gender differences in vulnerability to depression in adolescence have been widely investigated.6-10 Adolescent females have a higher incidence of major depressive disorder and a more chronic course than males when followed up at 30 years of age.11 A younger age of onset has been found to be the strongest predictor of severity in the course of depression in females.11 This suggests that there is a more substantial long-term impact of childhood depression in females than males.11

Female adolescents are in crisis. Nearly 57% of girls reported feeling persistently sad or hopeless in 2021, up from 36% in 2011 and the highest levels seen in the past decade.12 The reasons for the significant increase need to be clarified. Social media? School shootings? Change in parenting style? Climate change? No one knows for sure, and it is likely multifactorial. One of the factors to consider is the trend of female puberty beginning at earlier ages. Scientists are still trying to parse out why puberty is happening earlier. In the 1800s, girls began their periods around age 16; in the 1900s, it was around age 15; and in 2020, the average age was 11.13

Anxiety among adolescents has become a prominent and concerning issue in recent years, drawing significant attention from mental health experts and educators alike. The adolescent stage, characterized by rapid physical, emotional, and social changes, often becomes a breeding ground for various forms of anxiety. This period marks a critical developmental phase where young individuals navigate increasing pressures related to academics, social interactions, identity formation, and future uncertainties. Similar to depression, the prevalence of any anxiety disorder among adolescents is known to be higher in females (38.0%) than males (26.1%).4

Suicide

In recent years, there has been a rise in the suicide rate among adolescents, particularly among females. The most recent and comprehensive data is from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS)14, a CDC study conducted every other year that surveys thousands of high school-age children from public and private schools from grades 9 to 12 across all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia.

According to the CDC YRBSS, suicide is the 11th leading cause of death overall in the United States and the third among U.S. high school students from the ages of 14 to 18, which accounts for one-fifth of all deaths among this age group. The rate of death by suicide in people aged 10-24 years increased by 57.4% from 2007 to 2018.14 More recently, the number of teenage girls experiencing suicidal thoughts and behaviors increased during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 1).

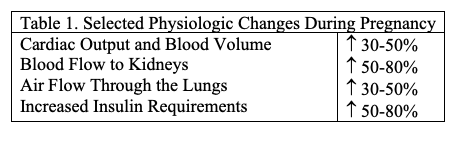

During the pandemic, the percentage of high school female students who seriously considered attempting suicide also rose, from 24.1% in 2019 to 30% in 2021 (Figure 2).12 In addition, differences in the frequency of suicidality are seen by students’ ages, race/ethnicity, and gender identity (Table 1). In 2021, Black female students were nearly 1.5 times more likely than white female students to report having attempted suicide. Additionally, LGBQ+ students reported having attempted suicide more frequently than heterosexual students, according to the CDC. Those identifying as lesbian or gay, bisexual, or questioning were found to have nearly 1.9, 3.3, and 1.5 times higher rates of suicide attempts compared to heterosexual students, respectively.

LGBTQ+

The LGBTQ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer/Questioning) community faces unique challenges that can significantly impact mental health, with depression being a prevalent concern. Members of this community often encounter societal stigma, discrimination, and a lack of understanding, leading to increased vulnerability to mental health issues such as depression. The struggles associated with self-acceptance, familial rejection, and societal pressures can contribute to higher rates of depression among LGBTQ individuals compared to the general population. Understanding these challenges is crucial in providing effective support and fostering a more inclusive and accepting environment for mental health within the LGBTQ community.

A significant amount of evidence exists affirming the mental health challenges common within the LGBTQ community. The Trevor Project’s 2023 US National Survey on the Mental Health of LGBTQ Young People found that over half of trans or nonbinary youth had seriously considered attempting suicide in the previous year.15 About 20% had attempted suicide in the last year, and about 3 in 5 transgender or nonbinary youth who wanted access to care were unable to get it.

Assessment and Treatment

Assessing pediatric depression and anxiety is a complex process that requires a multifaceted approach. Professionals use standardized questionnaires (e.g., Beck Depression Inventory, Patient health Questionnaire-9, Behavior Assessment System for children, Child Behavior Checklist, Hamilton Anxiety Scale) and interviews to gather information about the child’s mood, thoughts, and behaviors. Observing the child’s interactions and social behavior provides valuable insights into their emotional well-being. Furthermore, involving parents, teachers, and caregivers in the assessment process can offer a more comprehensive view of the child’s daily functioning and emotional struggles. It is crucial to consider cultural and environmental factors influencing a child’s experience. Overall, a thorough assessment of child depression and anxiety involves a combination of clinical interviews, behavioral observations, input from multiple sources, and culturally sensitive approaches to diagnose and support the child’s mental health needs accurately.

Treatment of childhood and adolescent depression and anxiety consists of psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, or a combination of these. The American Psychiatric Association and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry recommend that psychotherapy always be a component of treatment for childhood and adolescent depression.16 They recommend psychotherapy as an acceptable treatment option for patients with milder depression and a combination of medication and psychotherapy for those with moderate to severe depression.

Consensus guidelines recommend fluoxetine (Prozac), citalopram (Celexa), and sertraline (Zoloft) as first-line treatments for moderate to severe depression in children and adolescents.17 A Cochrane review found that fluoxetine was the only agent with consistent evidence (from three randomized trials) that it is effective in decreasing depressive symptoms.18 Treatment with fluoxetine alone or in combination with cognitive behaviors therapy (CBT) accelerates the response. Adding CBT to medication enhances its safety. Taking benefits and harms into account, the combined treatment appears superior to monotherapy as a treatment for major depression in adolescents.19

Childbearing and Reproductive Years

Depression and Anxiety

Depression and anxiety disorders represent significant global public health concerns, affecting individuals across the lifespan. In addition to the impact on quality of life and contributions to comorbid health concerns, depression, and anxiety disorders are estimated to cost the U.S. economy more than $300 billion per year in lost productivity, healthcare expenses, and other direct and indirect costs.20 Emerging evidence suggests that the prevalence, presentation, and impact of depression and anxiety may vary between men and women in adulthood. The 12-month prevalence of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders in U.S. adults is approximately 7% and 19%, respectively, with even higher lifetime prevalence. Epidemiological studies indicate that women are about twice as likely to experience both depression and anxiety compared with men and that rates of both disorders have increased in recent decades.4, 21, 22

Symptoms Between Men and Women

Many variables contribute to differences in the frequency and presentation of anxiety and depression between men and women, including biological, psychological, and sociocultural influences. Hormone differences, especially the hormonal fluctuations that occur during the menstrual cycle, perinatal period, and menopause, have been implicated in a higher prevalence of mood disorders among women.23 Women are more likely to report atypical symptoms of depression characterized by feeling excessively tired, increased appetite, and heavy feelings in the body and limbs, called leaden paralysis.24 In contrast, symptoms of emotional distress in men are more likely to present with somatic complaints, such as headaches, digestive issues, and muscle aches.25

Coping Styles

Men and women often have different coping styles in response to stressors, with women tending to internalize stress (symptoms of sadness, worthlessness, and guilt), leading to an increased susceptibility to depression and higher comorbidity with eating disorders. In contrast, men may exhibit externalizing behaviors (symptoms of irritability or anger), contributing to more risk-taking and higher rates of comorbid substance use disorders.26-28 Social expectations, gender roles, and stigma surrounding mental health issues further influence the recognition of emotional distress by shaping how men and women express and seek help, contributing to gender disparities in depression and anxiety.29

Perinatal Mood and Anxiety Disorders

Perinatal mood and anxiety disorders (PMADs; Figure 3) represent a spectrum of mental health conditions affecting women during pregnancy and the postpartum period. The burden of PMADs extends into maternal health outcomes, fetal health and wellbeing, maternal-infant bonding, childhood development, and overall family dynamics. Medical scientists and healthcare professionals are shifting toward the use of terminology that allows for recognition of the broad spectrum of mental illnesses that may occur during the peripartum period.

The term PMADs creates an umbrella that includes disorders of depression, bipolar disorders, anxiety, panic, obsessive-compulsive disorder, trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder, and psychosis. Approximately 1 in 5 women will experience a PMAD during the peripartum period [30]. In addition to the burden of mental health symptoms and impacts on functioning, PMADs contribute to an increased risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, NICU admissions, increased healthcare costs, and severe maternal morbidity and mortality.30 Although women have lower rates of suicide and suicide attempts in the peripartum period compared with the general population, suicide is considered one of the leading causes of maternal mortality in the first 12 months postpartum.31

Treatment Approaches

Treatment approaches for both depressive and anxiety disorders typically involve a combination of psychotherapy, medication, and lifestyle changes (Figure 4). Psychotherapy, such as CBT, is often considered to be the first-line treatment for depression and anxiety. Medication approaches for depression and anxiety are often similar as well, with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) being considered a first-line pharmacologic approach to address imbalances in neurotransmitters in the brain. Lifestyle changes, including regular exercise, a healthy diet, proper sleep, and stress management techniques, such as mindfulness, also play an essential role in symptom management.

The Perimenopausal, Menopausal, and Postmenopausal Period

Transitions

Advancing age and the transitions that often accompany later life, including retirement, financial hardships, increased isolation, deteriorating physical health, worsening medical problems, and death of friends and loved ones, can be risk factors for both depression and anxiety in older adults. Recent cohort studies and systematic reviews indicate that older women have an increased risk of major depression, as well as higher levels of depression and anxiety symptoms than men.32 Untreated depression and anxiety in older adults can lead to worsening symptoms of medical illnesses and memory problems, excess disability, premature institutionalization, more extended hospital stays, and increased mortality, including suicide in the individual, and significant economic costs to individuals, their families, and society in general.

Adults aged 65 and over are the fastest-growing segment of the US population and will continue to experience a “boom” in growth over the next few decades. Current general estimates of depression and anxiety are 20-25% and 14-17%, for ages 65 and older respectively. Prevalence rates are likely underestimated because detection and diagnosis of both depression and anxiety in later life are complicated by medical comorbidity, cognitive decline, and differences in the way older adults report symptoms.33, 34 Additionally, prevalence rates increase in settings such as hospitals and long-term care settings where medical comorbidity and disability are higher.

Stigma and Suicide

Due to stigma about mental health or misconceptions about aging, older adults will more often deny feelings of depression or anxiety when asked directly. Instead, they will more frequently present with vague or nonspecific physical symptoms. Often, depression and anxiety symptoms may be overlooked in the context of multiple or more acute medical problems. However, despite being less likely to report suicidal thoughts spontaneously, older adults are more honest when asked directly. This is clinically significant since older adults, particularly those aged 75 years and older, have among the highest suicide rates (20.3 per 100,000) compared to the general US population (14.5 per 100,000). Among adults aged 55 and older, men maintain consistently higher suicide rates than women as they continue to age. Comparatively, suicide rates in older women tend to decrease with increasing age. Still, suicide rates for men significantly increase with increasing age, reaching nearly 17 times higher in the age 85 and older group compared to women (Figure 5). Hence, older adults must be regularly screened for symptoms of depression and anxiety and asked directly regarding suicidal ideation and behaviors.

Depression

In older adults, depression can present as either a lifelong recurrent illness or as a new onset disorder. Depression in later life is often strongly related to other chronic health conditions. With the gender gap somewhat narrower in later life, particularly those over age 85, rates of depression appear to continue to be higher in older women than in older men and more significant than the two-fold difference seen across the rest of the adult lifespan.35 Depression is also one of the most common causes of pseudodementia, which is a treatable and reversible cause of dementia that should not be missed.

Anxiety disorders in later life are often comorbid with other mood and substance use disorders. Generalized anxiety and specific phobias (often fear of falling) are the more common anxiety disorders in later life. Prevalence rates for anxiety in later life tend to decrease when compared with younger age groups. Still, many of the current screening tools are not validated in the more medically complex older adult population, which may drastically underestimate rates.32 However, trends for higher prevalence rates for anxiety in women compared to men continue to hold into later life.

Treatment Approaches

In older adults, the first approach to the management of depression and anxiety should be to rule out any existing medical condition(s) or medication side effect(s) that may be exacerbating symptoms of depression or anxiety. When considering pharmacological treatment options, SSRIs are considered first-line for both depression and anxiety. Non-pharmacological options include psychotherapy, specifically CBT, with or without the concurrent use of medications. Electroconvulsive therapy can also be a very effective treatment for older adults with severe decompensated depression and multiple medication sensitivities. Clinical depression and anxiety disorders in later life should not be considered a normal part of aging, and successful treatment can dramatically improve outcomes and quality of life.

Conclusion

Throughout life, women need to prioritize self-care, seek support from friends, family, or mental health providers when needed, and practice coping strategies to manage stress and maintain emotional well-being. Across the lifespan, women tend to experience higher rates of depression and anxiety then men and the presentation and symptoms of anxiety and depression differ based on gender. The preferred treatment approaches such as cognitive behavioral therapy and pharmacological treatment options may be consistent across age yet a woman’s response to treatment may differ depending on the timing of the treatment and chronicity of her depression and/or anxiety. Providers are critical in educating women about the symptoms of depression and anxiety and helping with their identification and treatment. Promoting awareness of depression and anxiety, reducing stigma, and preventing suicide in women remains priority areas for improving women’s health across the lifespan.

References

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245-258. doi:10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8

- Danese A, McEwen BS. Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiol Behav. 2012;106(1):29-39. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.08.019

- Lewis AJ, Sae-Koew JH, Toumbourou JW, Rowland B. Gender differences in trajectories of depressive symptoms across childhood and adolescence: A multi-group growth mixture model. J Affect Disord. 2020;260:463-472. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2019.09.027

- Harvard Medical School, (2007). National Comorbidity Survey (NCS). (2017, August 21). Retrieved from https://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/index.php.

- Naninck EF, Lucassen PJ, Bakker J. Sex differences in adolescent depression: do sex hormones determine vulnerability? J Neuroendocrinol. 2011;23(5):383-392. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2826.2011.02125.x

- Makri-Botsari, E. Risk/protective effects on adolescent depression: Role of individual, family and peer factors. Psychological Studies. 2005; 50(1), 50-61.

- Patton GC, Olsson C, Bond L, Toumbourou JW, Carlin JB, Hemphill SA, Catalano RF. Predicting female depression across puberty: a two-nation longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(12):1424-32. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181886ebe. PMID: 18978636; PMCID: PMC2981098..

- Lewis AJ, Kremer P, Douglas K, Toumborou JW, Hameed MA, Patton GC, Williams J. Gender differences in adolescent depression: Differential female susceptibility to stressors affecting family functioning. Australian Journal of Psychology, 2015: 67(3), 131–139. doi:10.1111/ajpy.12086

- Lewis AJ, Rowland B, Tran A, et al. Adolescent depressive symptoms in India, Australia and USA: Exploratory Structural Equation Modelling of cross-national invariance and predictions by gender and age. J Affect Disord. 2017;212:150-159. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.01.020

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus JS. The emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence. Psychol Bull. 1994;115(3):424-443. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.115.3.424

- Essau CA, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Sasagawa S. Gender differences in the developmental course of depression. J Affect Disord. 2010;127(1-3):185-190. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2010.05.016

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Data Summary & Trends Report: 2011-2021. 2023.

- Bellis MA, Downing J, Ashton JR. Adults at 12? Trends in puberty and their public health consequences. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006 Nov;60(11):910-1. doi:10.1136/jech.2006.049379. PMID: 17053275; PMCID: PMC2465479.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Survey: data summary and trends report 2009-2019. US Department of Health and Human Services. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/YRBSDataSummaryTrendsReport2019-508.pdf

- 2023 U.S. National Survey on the Mental health of LGBTQ Young People/ Accessed Mar 29, 2024. https://www.thetrevorproject.org/survey-2023/

- American Psychiatric Association, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. The use of medication in treating childhood and adolescent depression: information for patients and families. http://www.parentsmedguide.org/parentsmedguide.pdf.

- Hughes CW, Emslie GJ, Crismon ML, et al. Texas Children’s Medication Algorithm Project: update from Texas Consensus Conference Panel on Medication Treatment of Childhood Major Depressive Disorder. J Amer Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(6):667-686.

- Hetrick S, Merry S, McKenzie J, Sindahl P, Proctor M. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for depressive disorders in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Jul 18;(3):CD004851. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004851.pub2. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD004851. PMID: 17636776.

- March, JS, et al. The Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS). Archives of General Psychiatry. 01 Oct 2007, 64(10):1132-1143

- Greenberg PE, Fournier AA, Sisitsky T, Simes M, Berman R, Koenigsberg SH, Kessler RC. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2010 and 2018). PharmacoEconomics, 2021:39(6). doi:10.1007/s40273-021-01019-4

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, Rush AJ, Walters EE, Wang PS. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA, 2003:289(23), 3095. doi:10.1001/jama.289.23.3095

- Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, WittchenHU. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 2012:21(3), 169–184. doi:10.1002/mpr.1359

- Albert, P. Why is depression more prevalent in women? Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience, 2012:40(4), 219–221. doi:10.1503/jpn.150205

- Altemus, M., Sarvaiya, N., & Neill Epperson, C. Sex differences in anxiety and depression clinical perspectives. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 2014:35(3), 320–330. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2014.05.004

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Emotion regulation and psychopathology: The role of gender. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 2012:8(1), 161–187. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143109

- Kendler KS, Gatz M, Gardner CO, Pedersen NL. A Swedish national twin study of lifetime major depression. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 2006:163(1), 109–114. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.109

- Kessler, R. Sex and depression in the National Comorbidity Survey I: Lifetime prevalence, chronicity and recurrence. Journal of Affective Disorders, 1993:29(2-3), 85–96. doi:10.1016/0165-0327(93)90026-g

- Addis ME, Mahalik JR. Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. American Psychologist, 2003:58(1), 5–14. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.5

- Ayala NK, Lewkowitz AK, Whelan AR, Miller ES. Perinatal Mental Health Disorders: A Review of Lessons Learned from Obstetric Care Settings. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 2023:19, 427–432. doi:10.2147/ndt.s292734

- McKee K, Admon LK, Winkelman TN, Muzik M, Hall S, Dalton VK, Zivin K. Perinatal mood and anxiety disorders, serious mental illness, and delivery-related health outcomes, United States, 2006–2015. BMC Women’s Health, 2020:20(1). doi:10.1186/s12905-020-00996-6

- Orsolini L, Valchera A, Vecchiotti R, et al. Suicide during perinatal period: Epidemiology, risk factors, and clinical correlates. Frontiers in Psychiatry,2016:7:138. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00138

- Kiely KM, Brady B, Byles J. Gender, mental health, ageing. Maturitas. 2019:129: 76-84.

- Djern JK. Prevalence and predictors of depression in populations of elderly: A review. Acta Psychiatr. Scan. 2006:113: 372-87.

- Fiske A, Wetherell IL, Gatz M. Depression in older adults. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2009;5: 363-389.

- Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Castriolla N, Jenze EJ, Stanley MA, Craske MG. Anxiety disorders in older adults: A comprehensive review. Depression and Anxiety. 2010 Feb;27(2):190-211. doi:10.1002/da.20653. PMID:20099273

Citation

Burris, M, Benson, C, Purganan, K, Wall, D, & Bakian AV. (2024). Depression and Anxiety in Women. Utah Women’s Health Review.