Letter from the Editor, Karen Schliep, PhD MSPH, 2023-24

It is with great enthusiasm and deep appreciation that I present to you the 2023/2024 issue of the Utah Women’s Health Review. This issue is a testament to the power of interdisciplinary collaboration, community engagement, and a growing momentum in Utah and beyond to advance women’s health research across the lifespan.

This year’s Review includes a special section led by my esteemed colleagues Drs. Caren Frost and Lisa Gren, who have long championed equity and inclusion in research. Their 2024 Special Issue, featuring eight compelling essays and research articles, challenges us to reimagine what equitable and respectful health care looks like for women of diverse identities and experiences. From innovative community-based methodologies to policy-driven advocacy, this body of work underscores the importance of listening to women’s voices as we shape systems of care.

We also highlight the dynamic conversations and discoveries from three symposia held over the past year. The 2023 symposium Women, Disrupted invited us to consider the environmental, endocrine, emotional, economic, and equity-driven forces that converge to shape women’s health. The conversations that emerged were both sobering and empowering—reminding us that while disruption can signify breakdown, it can also signal opportunity for transformation.

Our 2024 Stillbirth Symposium brought together clinicians, researchers, and families to grapple with one of the most heartbreaking yet under-discussed aspects of reproductive health. The urgency of this work is reflected in the symposium’s call for standardized care pathways, expanded support for bereaved families, and investments in stillbirth prevention and surveillance.

The Women’s Health in the Cross Hairs symposium explored the intersection of politics, policy, and reproductive health, emphasizing the growing need for evidence-informed advocacy in a rapidly shifting national landscape. Panelists drew attention to the unintended consequences of restrictive reproductive health legislation and urged academic institutions to take an active role in protecting women’s bodily autonomy and access to care.

This issue also features a diverse set of original research articles utilizing data from the Utah Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), as well as other state-level and institutional datasets. These studies offer critical insights into maternal mental health, pregnancy complications, occupational exposures, and sex-based differences in clinical care:

- One study examines the nuanced relationship between preconception polycystic ovary syndrome and gestational diabetes, exploring how co-occurring hypertension may influence this association.

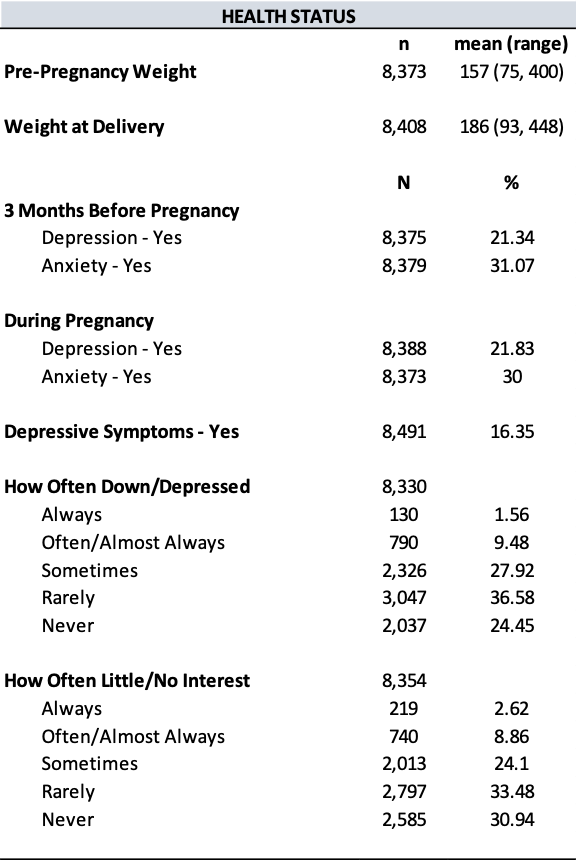

- Another study investigates the link between prenatal depression and anxiety and the risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy—highlighting the growing need for integrated behavioral health screening during prenatal care.

- A third paper assesses whether maternal age modifies the relationship between gestational diabetes and primary C-section delivery, providing implications for age-specific prenatal counseling.

- The occupational health study on Utah nail technicians raises critical questions about workplace exposures and miscarriage risk—an area ripe for public health intervention.

- Additional articles shed light on the role of nurses and integrated behavioral health professionals in addressing rising rates of perinatal depression, and on disparities in pain management practices among college athletes by sex.

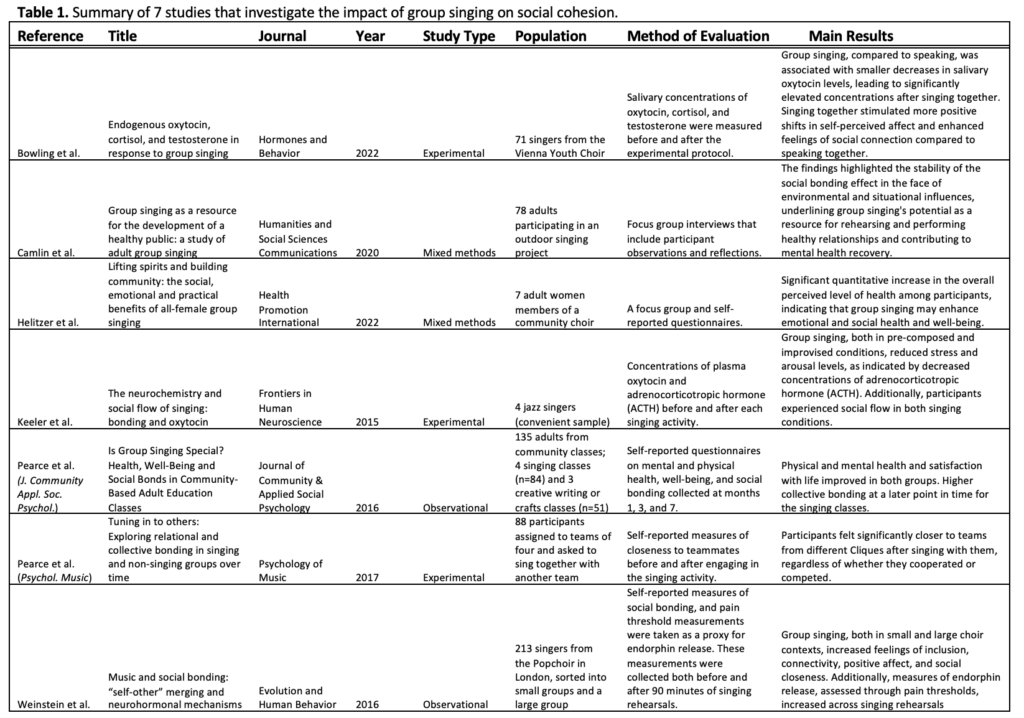

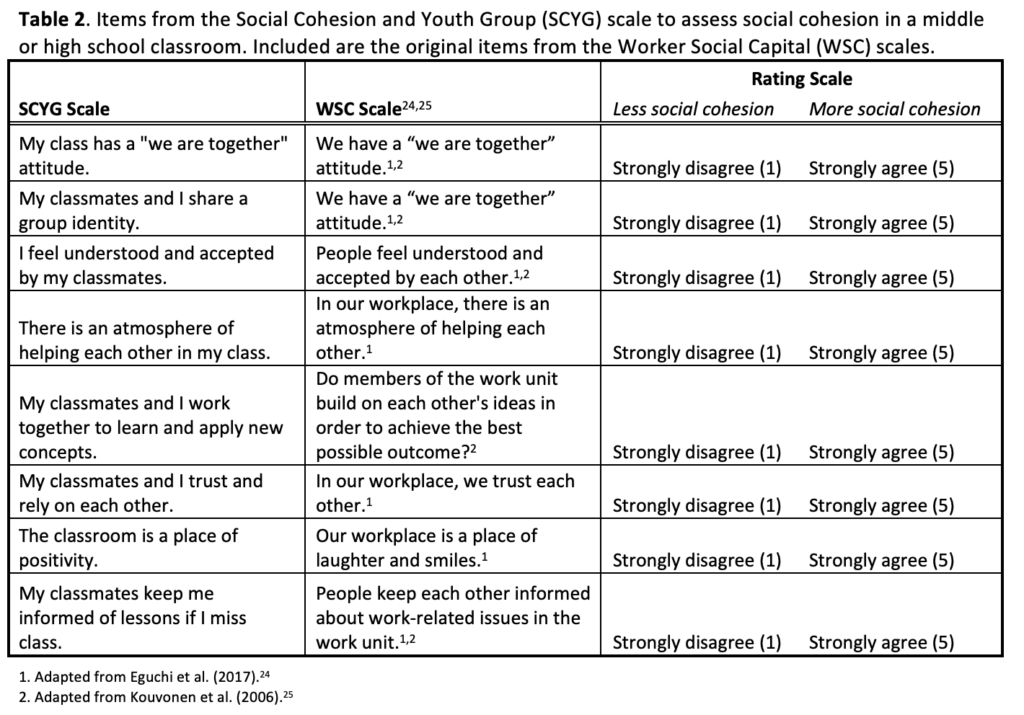

Rounding out the issue are three timely data snapshots designed to catalyze dialogue and action. These brief reports address the role of group singing in fostering youth social cohesion, trends in shared reading to support early childhood literacy, and the barriers that women of color in Utah face in maintaining healthy lifestyles. Each of these snapshots underscores the importance of upstream social determinants in shaping long-term health outcomes.

As Editor-in-Chief, I continue to be inspired by the breadth and depth of work being done across Utah to improve women’s health. This issue reflects our collective commitment to lifting up women’s experiences, challenging structural inequities, and advancing science that informs practice and policy. I extend my deepest gratitude to our editorial team, contributing authors, peer reviewers, and the many community partners whose dedication and insights make this work possible.

Thank you for joining us in this important conversation. I hope the articles in this issue spark new ideas, collaborations, and commitments to improving the health and well-being of all women in Utah and beyond.

Warmly,

Karen C. Schliep, PhD, MSPH

Editor-in-Chief, Utah Women’s Health Review

Does Maternal Age Modify the Association Between Gestational Diabetes and Primary C-section Delivery? A Cross-Sectional Study of Utah PRAMS Data

Abstract

Background: Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is prevalent in expecting mothers and is associated with various adverse maternal and fetal outcomes. Previous studies suggest a relationship between GDM and cesarean section (CS). However, the results of these studies in the context of primary CS and mothers’ age are limited and inconsistent, when other factors are accounted for.

Objective: This study compared primary CS risk between younger (15-34 years) and older (35+) mothers with GDM in Utah.

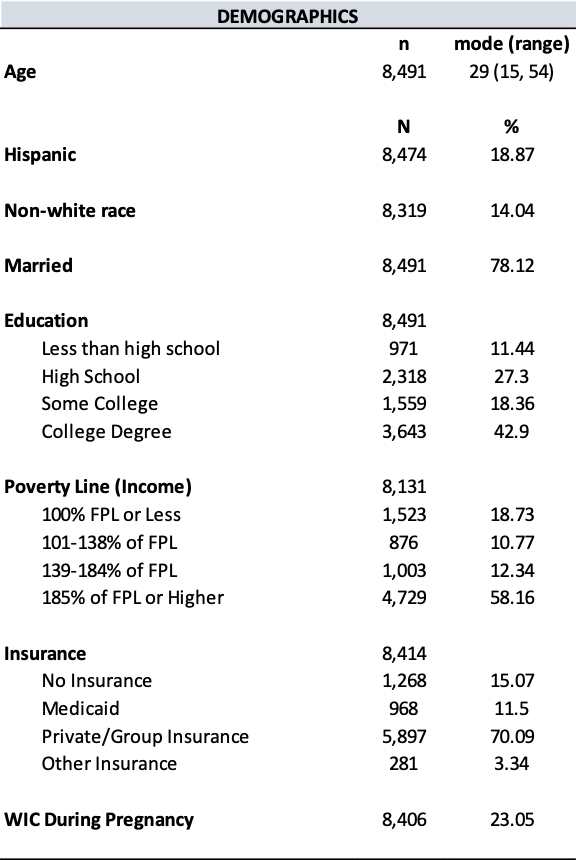

Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional analysis using the Utah Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) phase 8 (2016-2021) survey data. A total of 8,491 responses were available for analysis. We estimated the risk/prevalence ratio (PR) of primary CS in women with GDM using Poisson regression models.

Results: 18.44% of women with GDM also had a primary CS, compared to 10.95% with no GDM. Overall, GDM significantly increased primary CS risk (PR 1.39: 1.13, 1.72). Younger mothers (15-34) with GDM also had a stronger adjusted risk (PR 1.48: 1.15, 1.91), but not older mothers (PR 1.40: 0.95, 2.07).

Conclusion: This study found greater primary CS risk in younger mothers with GDM but not older mothers. Longitudinal studies and interventions focusing on modifiable risk factors in younger Utah mothers are warranted to enhance their health during pregnancy and childbirth. More research is also needed to better understand CS decisions among younger Utah mothers, in particular, those who develop comorbidities such as GDM.

Implications: Culturally and demographically tailored interventions are needed to reduce GDM and associated primary CS risk in this population.

Introduction

Gestational Diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a common complication during pregnancy, affecting more than 14% of pregnancies globally and 9% of pregnancies in the United States (US).1,2 In Utah, around 7.5% of pregnancies are affected by GDM.3 Some identified risk factors for GDM include advanced maternal age, obesity, and type 2 diabetes mellitus.4 Also, expecting mothers with GDM face an increased risk of preeclampsia, premature birth, cesarean section delivery (CS), and cardiovascular disease mortality.5,6

Among the various complications linked to GDM, a major concern is its strong association with CS. In the US, CS is among the most common major surgical procedures performed, accounting for 32.1% of births in 2022.7 In Utah, CS prevalence was 26.3% among low risk mothers with no prior births, in the same year.8 This is noteworthy as CS is also associated with adverse maternal outcomes such as endomyometritis, uterine rupture, and death.9,10

GDM is an independent predictor of CS in multiple previous studies.11–14 However, there are direct contradictions surrounding the context of maternal age in the association between GDM and CS, when other factors are accounted for.13,14 For example, one group found that the risk of CS was only increased in mothers aged 45 years or older.14 Other literature suggests a strong correlation of GDM and CS risk with increased age.13 Currently, there is no research investigating how maternal age may modify this association.

Generally, studies indicate age as a confounder, given that advanced maternal age has historically been linked to higher GDM and CS risks.13 However, recent reports suggest that younger mothers (under 35 years) may also face elevated risks of both conditions.7,15 Also, there are no studies assessing differences between younger and older mothers with GDM in the risk of a first or primary CS; most existing research has focused on total CS, history of CS, or repeat CS,11,13,16 requiring further investigation.

Moreover, to our knowledge, there has been no research examining age differences in primary CS risk within Utah mothers with GDM. To overcome these gaps, we utilized data from the Utah Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) phase 8 survey data, which included 8,491 mothers. We analyzed the data by stratifying mothers with GDM into two groups: younger (15-34 years) and older (35+), to assess their risk of a primary CS.

Methods

Study Design and Population

This study utilized the Utah Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) phase 8 (2016-2021) survey data for analysis. PRAMS is an ongoing population-based survey designed to collect information on maternal behaviors and experiences before, during, and immediately following pregnancy.17 Approximately 200 new mothers are randomly selected monthly for participation using Utah Birth Certificates. All responses are linked to the birth certificate record throughout the data collection process. Responses to the PRAMS survey are also weighted to accurately represent all women given birth in Utah.17 The dataset for the present study included 8,491 women, which reflected an extrapolated population size of 279,355 women in Utah (after weighing) using SAS analytical software package.

Exposure

The primary exposure was GDM, categorized as “Yes” or “No.” The information on GDM status was obtained from the PRAMS dataset which was linked to the infant’s birth certificate record.

Outcome

The outcome of interest was primary CS delivery categorized as “Yes” or “No.” The information on CS delivery was obtained from the PRAMS dataset which was linked to the infant’s birth certificate record.A “yes” for primary CS delivery indicates women with their first CS delivery reported in the birth certificate records, irrespective of the number of previous live births.

Covariates

Covariates used in the study included age (<20, 20-24, 25-34, and 35+ years of age), race (white or non-white), ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic), degree attained (associate’s degree or lower, bachelor’s degrees or higher, and unknown degree), region of residence (urban or rural), body mass index BMI (underweight: <18.5 kg/m2; healthy weight: 18.5-24.9 kg/m2; overweight: 25-29.9 kg/m2; and obese: >30 kg/m2),18 hypertension (yes or no), number of previous live births (0, 1-2, 3-4, and 5 or more), and infant birth weight (grams).

Statistical Analysis

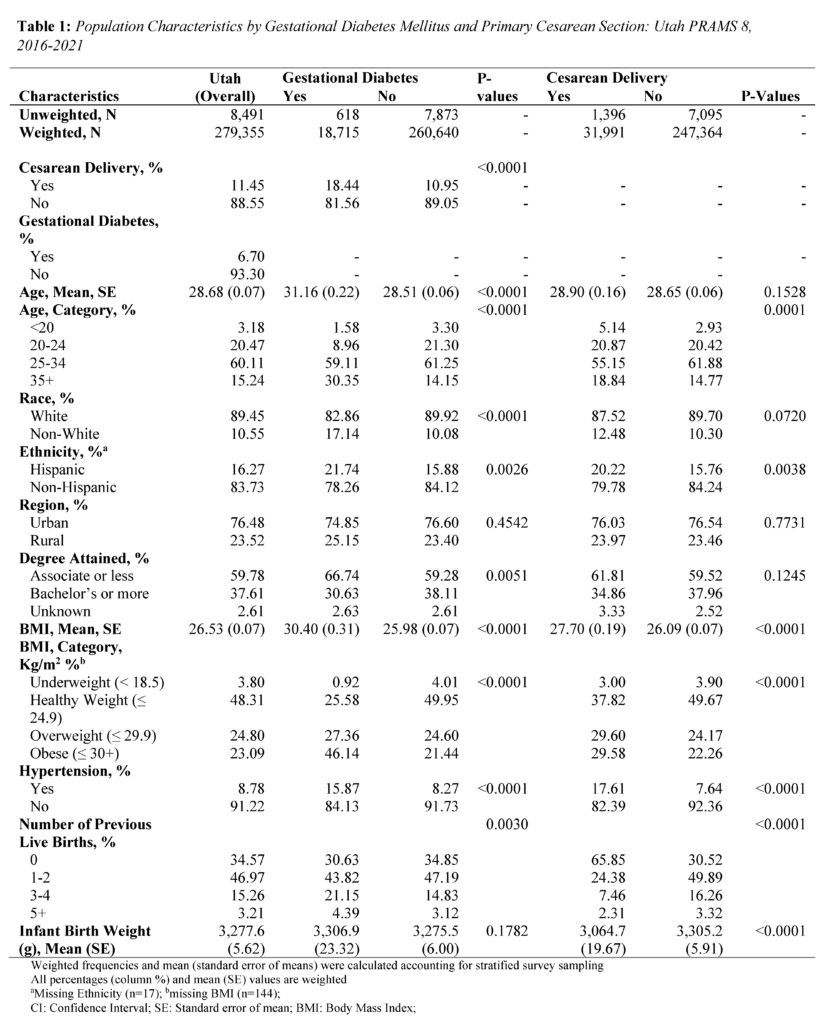

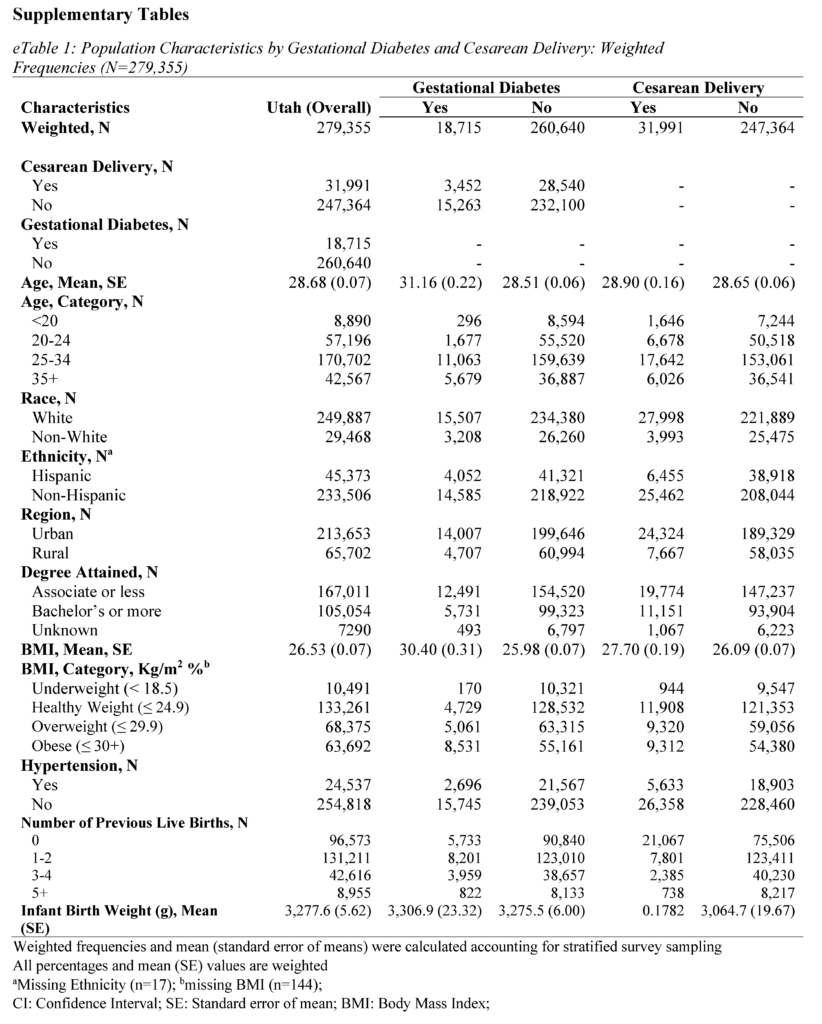

All analyses were conducted using SAS Studio (version 9.4). Sampling weights were applied to the analysis to obtain representative Utah population estimates. The PRAMS weighing methodology was provided by the CDC and Utah Department of Health and Human Services (UDHHS).19 Group differences for sample characteristics were calculated using chi-squared tests for categorical variables and student t-tests for continuous variables. The frequency distributions by GDM and primary CS are presented in Table 1 and eTables 1 and 2 (see Supplementary Materials).

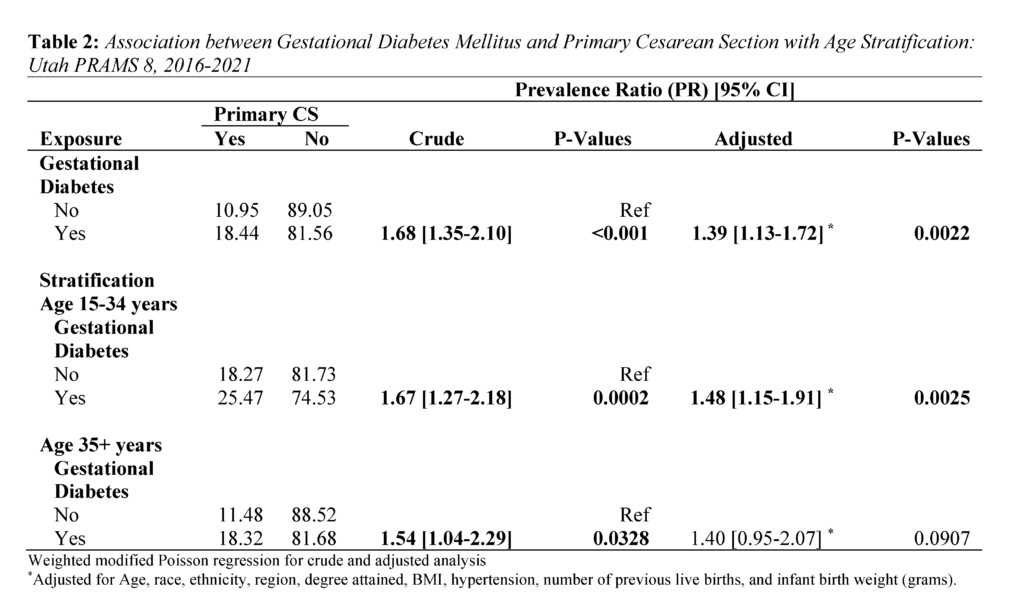

The modified Poisson regression was used to examine weighted crude and adjusted associations between GDM and CS.20 Prevalence Ratio (PR) estimates of the regression analysis are presented in Table 2. The Poisson regression was also used for age-stratified analysis of primary CS risk. Individual estimates for younger (15-34 years) and older mothers (35+) are also in Table 2. Age 35 and older was used as the cutoff point for stratification due to research suggesting 35 years as advanced maternal age.21

Ethics Approval

The collection of the data used in this study was approved by Utah Department of Health and Human Services (UDHHS) institutional review board.

Results

Population Characteristics

The study consisted of 8,491 respondents, reflecting 279,355 women giving birth in Utah after weighting. Mean (standard error) age was 28.68 (0.07) years, 89.45% identified as White race, and 83.73% identified as non-Hispanic ethnicity (Tables 1 and 2). In addition, 76.48% of women in the study lived in an urban setting, and 59.78% held an associate degree or lower.

About 6.70% of mothers in the study were diagnosed with GDM, and 11.45% of mothers had a primary CS. Mothers with GDM were more often older, evidenced by a mean age of 31.16 (standard error; SE = 0.22) years compared to 28.51 (SE = 0.06) years among mothers without GDM (P<.0001) (Table 1). Differences were observed between mothers with GDM and those without GDM in terms of race (P<.0001), ethnicity (P=0.0026), degree attainment (P=0.0051), BMI (P<.0001), comorbidity of hypertension (P<.0001), and number of previous live births (P=0.0030). (Table 1). Mothers with primary CS were more often Hispanic ethnicity (P=0.0038), had a higher BMI (P<.0001), comorbidity of hypertension (P<.0001), no previous live births (P<.0001), and lower infant birth weight (P<.0001).

Regarding the distribution of primary CS by GDM, 18.44% of mothers with GDM had primary CS, while 10.95% of mothers without GDM had a primary CS (P<.0001) (Table 1). Further, among younger mothers (15-34 years) with GDM, 25.47% had a primary CS. In contrast, among older mothers (35+) with GDM, 18.32% had a primary CS (Table 2).

Association between GDM and Primary CS delivery

Overall, GDM was strongly associated with primary CS (Table 2). Mothers with GDM had a 1.39 times higher adjusted risk of primary CS compared to those without GDM (PR 1.39: 1.13, 1.72). In the age stratified analysis, the adjusted risk of primary CS was 1.48 times significantly higher for mothers aged 15-34 (PR 1.48: 1.15, 1.91). In contrast, the adjusted risk for mothers aged 35+ years was (PR 1.40: 0.95, 2.07).

Discussion

Principal Findings

The present study provides a first look at primary CS risk in Utah mothers with GDM. It is unique in that it investigated differences between younger (15-34 years) and older (35+) mothers. We found that Utah mothers with GDM had a significantly higher risk of primary CS, and observed a stronger association in younger mothers (15-34 years).

Interpretation

Our first major finding regarding a higher risk of primary CS in mothers with GDM is consistent with other research.23 For example, the 2024 study by Fresch et al.23 found a 1.34 times higher adjusted risk of primary CS in mothers with GDM (PR 1.34: 1.31, 1.36). Medical conditions like suspected macrosomia, labor arrest, and indeterminate fetal heart rate tracing may make vaginal birth difficult and unsafe, requiring a CS.16,24 Importantly, GDM is a known independent risk factor which can exacerbate the occurrence of these conditions.24–26

In our second major finding, the risk of primary CS in mothers with GDM was higher across age groups but only significant for younger mothers ages 15-34. The estimates for this age group (PR 1.48: 1.15, 1.91) were higher than those of the overall population (PR 1.39: 1.13, 1.72). This result is surprising given that research generally indicates greater GDM and primary CS risk in advanced or older maternal age only.27 It is important to note that existing research has not specifically examined the associations in younger mothers. Instead, these studies have only used younger age as a comparison or reference group in their analyses.23,27 A recent US-based study, however, comparing primary CS prevalence between 2021 and 2022 showed increases for mothers ages 25-29 (21.0% vs 21.1%), 30-34 (33.8% vs 33.9%), 35-39 (26.1% vs 26.4%), and 40+ (33.7% vs 34.0%).7,28 The upward trend in younger mothers is noteworthy and highlights two key considerations. First, the risk of pregnancy complications in this age group may be higher than current estimates indicate. Second, younger expecting mothers may be underrepresented in maternity health research.

Several factors may be contributing to the rising CS rates among younger mothers. Common reasons include fear of labor pain (as a first time mother or following a previous birth), concerns about bodily changes and damage, concerns about their baby’s health, and convenience of scheduling a CS birth.29,30 In Utah, a 2013 PRAMS data report revealed labor challenges indicated by fetal monitor, prolonged labor, and failed labor induction as reasons for CS in mothers reporting a primary CS.31 Given that GDM is associated with many, if not all, of these complications, it is possible that a diagnosis of the condition may heighten fear of a vaginal delivery, particularly among younger expecting mothers, which may result in preference for a CS. We recommend further research be performed to confirm this relationship.

Health Implications

CS intersects with various domains of health. In terms of physical health, CS has associated complications for both the mother and child. CS is a risk factor for common gynecological conditions, including the development of urinary tract infections, gastrointestinal problems, adhesions, pain, infertility, painful menses, and endometriosis in the mother.9,32 Additionally, children born via CS are at increased risk for respiratory tract infections, asthma, and obesity.33

The economic health domain is also impacted. On average, CS is more costly for the patient and for the hospital than vaginal delivery. Across Utah, total CS costs are reported as $8,952.52 for those with insurance and $14,252.80 for those without insurance while vaginal births are reported as $5,951.76 and $10,199.52 with and without insurance, respectively.34 Much of this cost is taken care of by insurance companies. However, these costs do not consider any complications stemming from delivery or care for mother or child. For the social health domain, CS can impact family planning and relationships due to potential complications such as painful intercourse and infertility.9,32,35 In mental and behavioral health, the increased risk of complications and the recovery process resulting from CS can lead to stress, anxiety, and even delayed initiation of breastfeeding.36,37

In 2023, Utah’s CS rate (19.4%) was lower than the average rate across the United States (US, 26.3%) for low-risk women without prior births.8 This trend has remained consistent over time (2013-2023).8 Additionally, Utah has a lower rate of GDM (7.5%) compared to the US (9%), although this difference is small.3 One explanation for this difference is the younger age of mothers at their first birth in Utah compared to the US (25.9 in Utah versus 27.1 years overall in 2020).38

It is critical that the aforementioned issues are addressed to improve maternal and child health outcomes. We recommend the following actions for health systems and population health researchers in Utah. First, the necessity of CS should be carefully considered in the context of each expecting mother. It is equally important that cases of CS in young expecting mothers with GDM are closely reviewed to ensure that decisions for CS follow appropriate clinical guidelines. Second, health systems should provide interdisciplinary team-based care to support young mothers who develop comorbidities (such as GDM) to mitigate fear and worry about their pregnancy. Third, significant outreach is needed to increase awareness about comorbidities during pregnancy and how expecting mothers can protect their health and the health of their baby. Lastly, more work is needed in Utah to ensure that new and expecting younger mothers are represented in maternity health research.

Conclusions

In summary, this study contributes valuable insights into the association between GDM and primary CS in Utah, highlighting the importance of early detection and management of GDM to optimize maternal and infant health outcomes. Longitudinal studies and interventions focusing on modifiable risk factors in younger Utah mothers are warranted to enhance their health during pregnancy and childbirth. More research is also needed to better understand CS decisions among younger Utah mothers, in particular, those who develop comorbidities such as GDM.

Strengths & Limitations

This study had several strengths and limitations. First, our weighted sample was representative of the Utah population (279,355). This enabled more precise estimates and comprehensive evaluation of overall findings. Second, this study was unique as it is the first to examine GDM and the risk of CS within the Utah population. Concerning limitations, since the study utilized Utah population data, the findings may not be generalizable to other areas. Further, the study design was cross-sectional, which introduces temporal ambiguity. As this analysis was done at one point, it cannot establish a cause-and-effect relationship.

Acknowledgements

Data was provided by the Utah Pregnancy Risk Assessment and Monitoring System (PRAMS), a project of the UDHHS, Office of Maternal and Child Health (MCH). No funding was provided for the project. This information or content and conclusions are those of the author and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by UDHHS MCH.

References

1. Wang H, Li N, Chivese T, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Estimation of Global and Regional Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Prevalence for 2021 by International Association of Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group’s Criteria. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183:109050. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109050

2. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. About Gestational Diabetes. Diabetes. Published May 31, 2024. Accessed July 25, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/about/gestational-diabetes.html

3. Utah Department of Health and Human Services. IBIS-PH – Health Indicator Report – Diabetes: gestational diabetes. Accessed July 24, 2024. https://ibis.utah.gov/ibisph-view/indicator/view/DiabGestDiab.html

4. Casagrande SS, Linder B, Cowie CC. Prevalence of gestational diabetes and subsequent Type 2 diabetes among U.S. women. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;141:200-208. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2018.05.010

5. Preda A, Pădureanu V, Moța M, et al. Analysis of Maternal and Neonatal Complications in a Group of Patients with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57(11):1170. doi:10.3390/medicina57111170

6. Wang YX, Mitsunami M, Manson JE, et al. Association of Gestational Diabetes With Subsequent Long-Term Risk of Mortality. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2023;183(11):1204-1213. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.4401

7. Osterman M, Hamilton B, Martin J, Driscoll A. National Vital Statistics Reports Volume 73, Number 2, April 4, 2024. Published online April 4, 2024.

8. Utah Department of Health and Human Services. IBIS-PH – Health Indicator Report – Cesarean delivery among low risk women with no prior births. Accessed July 24, 2024. https://ibis.utah.gov/ibisph-view/indicator/view/CesDel.UT_US.html

9. Quinlan JD, Murphy NJ. Cesarean Delivery: Counseling Issues and Complication Management. afp. 2015;91(3):178-184.

10. Boyle A, Reddy UM, Landy HJ, Huang CC, Driggers RW, Laughon SK. Primary Cesarean Delivery in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(1):33-40. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182952242

11. Gorgal R, Gonçalves E, Barros M, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus: A risk factor for non-elective cesarean section. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 2012;38(1):154-159. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0756.2011.01659.x

12. Song J, Cai R. Interaction between smoking during pregnancy and gestational diabetes mellitus and the risk of cesarean delivery: evidence from the National Vital Statistics System 2019. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2023;36(2):2259048. doi:10.1080/14767058.2023.2259048

13. Akinyemi OA, Weldeslase TA, Odusanya E, et al. Profiles and Outcomes of Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in the United States. Cureus. 2023;15(7):e41360. doi:10.7759/cureus.41360

14. Claramonte Nieto M, Meler Barrabes E, Garcia Martínez S, Gutiérrez Prat M, Serra Zantop B. Impact of aging on obstetric outcomes: defining advanced maternal age in Barcelona. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2019;19(1):342. doi:10.1186/s12884-019-2415-3

15. Shah NS, Wang MC, Freaney PM, et al. Trends in Gestational Diabetes at First Live Birth by Race and Ethnicity in the US, 2011-2019. JAMA. 2021;326(7):660-669. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.7217

16. Caughey AB, Cahill AG, Guise JM, Rouse DJ. Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2014;210(3):179-193. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.01.026

17. Utah Department of Health and Human Services. Utah PRAMS | Maternal and Infant Health Program. Accessed July 25, 2024. https://mihp.utah.gov/pregnancy-and-risk-assessment

18. CDC. Defining Adult Overweight and Obesity. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published June 3, 2022. Accessed September 28, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/basics/adult-defining.html

19. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Data Methodology. Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS). Published May 20, 2024. Accessed July 25, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/prams/php/methodology/index.html

20. Lindquist K. How can I estimate relative risk in SAS using proc genmod for common outcomes in cohort studies? | SAS FAQ. Accessed January 17, 2024. https://stats.oarc.ucla.edu/sas/faq/how-can-i-estimate-relative-risk-in-sas-using-proc-genmod-for-common-outcomes-in-cohort-studies/

21. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Pregnancy at Age 35 Years or Older: ACOG Obstetric Care Consensus No. 11. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2022;140(2):348. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004873

22. Marshall SW. Power for tests of interaction: effect of raising the Type I error rate. Epidemiol Perspect Innov. 2007;4:4. doi:10.1186/1742-5573-4-4

23. Fresch R, Stephens K, DeFranco E. The Combined Influence of Maternal Medical Conditions on the Risk of Primary Cesarean Delivery. AJP Rep. 2024;14(1):e51-e56. doi:10.1055/s-0043-1777996

24. Kc K, Shakya S, Zhang H. Gestational diabetes mellitus and macrosomia: a literature review. Ann Nutr Metab. 2015;66 Suppl 2:14-20. doi:10.1159/000371628

25. Gill P, Henning JM, Carlson K, Van Hook JW. Abnormal Labor. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Accessed July 26, 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459260/

26. Depla AL, De Wit L, Steenhuis TJ, et al. Effect of maternal diabetes on fetal heart function on echocardiography: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2021;57(4):539-550. doi:10.1002/uog.22163

27. Richards MK, Flanagan MR, Littman AJ, Burke AK, Callegari LS. Primary cesarean section and adverse delivery outcomes among women of very advanced maternal age. J Perinatol. 2016;36(4):272-277. doi:10.1038/jp.2015.204

28. Osterman MJK, Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Driscoll AK, Valenzuela CP. Births: Final Data for 2021. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2023;72(1):1-53.

29. Stoll KH, Hauck YL, Downe S, Payne D, Hall WA. Preference for cesarean section in young nulligravid women in eight OECD countries and implications for reproductive health education. Reprod Health. 2017;14:116. doi:10.1186/s12978-017-0354-x

30. Stoll K, Edmonds JK, Hall WA. Fear of Childbirth and Preference for Cesarean Delivery Among Young American Women Before Childbirth: A Survey Study. Birth. 2015;42(3):270-276. doi:10.1111/birt.12178

31. Utah Department of Health and Human Services. Utah Health Status Update: Primary Cesarean Delivery. Published June 2013. Accessed July 26, 2024. https://ibis.utah.gov/ibisph-view/pdf/opha/publication/hsu/2013/1306_CSection.pdf

32. Antoine C, Young BK. Cesarean section one hundred years 1920-2020: the Good, the Bad and the Ugly. J Perinat Med. 2020;49(1):5-16. doi:10.1515/jpm-2020-0305

33. Słabuszewska-Jóźwiak A, Szymański JK, Ciebiera M, Sarecka-Hujar B, Jakiel G. Pediatrics Consequences of Caesarean Section-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):8031. doi:10.3390/ijerph17218031

34. Peter K. Costs of Childbirth by State. PolicyScout. August 17, 2022. Accessed August 15, 2024. https://policyscout.com/health-insurance/learn/costs-childbirth-by-state#

35. Kainu JP, Sarvela J, Tiippana E, Halmesmäki E, Korttila KT. Persistent pain after caesarean section and vaginal birth: a cohort study. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2010;19(1):4-9. doi:10.1016/j.ijoa.2009.03.013

36. Skov SK, Hjorth S, Kirkegaard H, Olsen J, Nohr EA. Mode of delivery and short-term maternal mental health: A follow-up study in the Danish National Birth Cohort. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2022;159(2):457-465. doi:10.1002/ijgo.14155

37. Hosaini S, Yazdkhasti M, Moafi Ghafari F, Mohamadi F, Kamran Rad SHR, Mahmoodi Z. The relationships of spiritual health, pregnancy worries and stress and perceived social support with childbirth fear and experience: A path analysis. PLoS One. 2023;18(12):e0294910. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0294910

38. Pieper K, Seager M, Blackburn R. Utah Women and Fertility: Trends and Changes from 1970–2021. Published online April 4, 2023.

Supplementary Materials

Citation

Adediran E, Duffy HR, & Asay KM. (2024). Does Maternal Age Modify the Association Between Gestational Diabetes and Primary C-section Delivery? A Cross-Sectional Study of Utah PRAMS Data. Utah Women’s Health Review. doi: 10.26054/d-yx18-mp3d

Prenatal Depression and Anxiety and Risk of Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy: Findings from the Utah Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring Survey (2016–2020)

Abstract

Objectives: Depression during pregnancy has recently been found to affect the risk of hypertensive pregnancy disorders. However, few studies have looked at the effect of having depression or anxiety prior to pregnancy and its effects on hypertensive pregnancy disorders (HDP). This study aims to analyze a population-based sample of at-risk pregnant women in Utah using the Utah Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (UT-PRAMS) to discover whether there is an association between pre-pregnancy depression/anxiety and HDP.

Methods: The study analyzed responses from the Utah Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (UT-PRAMS) Phase 8 questionnaire between 2016 and 2020 using descriptive statistics and robust Poisson distribution models.

Results: Women who reported pre-pregnancy depression and/or anxiety, compared to those who did not, had a 3–5% higher risk of having an HDP after adjusting for important sociodemographic, reproductive history, and lifestyle factors. The risk increased to 30–49% when using our more severe HDP definition, as used in prior studies, which combined self-report of HDP and birth-certificate verified preterm births.

Conclusions and Implications: These results slightly differ from the observations made in the Pregnancy Outcomes and Community Health (POUCH) study. While our study did not take into account the length of depression or anxiety symptoms or subcategorize HDP types (i.e., preeclampsia), this study made similar adjustments to maternal sociodemographic factors and found a more significant association with pre-pregnancy anxiety than depression.

Introduction

Depression during pregnancy is thought to impact 10–20% of US women. 1 It is a common concern that has been associated with several adverse pregnancy complications, including hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP).2 HDP, such as preeclampsia, eclampsia, and gestational hypertension, affect approximately one in seven delivery hospitalizations and are conditions that can cause serious health problems for both the mother and the baby across the lifespan.3

Cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors, including inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction, are expected to affect both depression and HDP, supporting common contributing mechanisms for both conditions.4 Despite the growing evidence of the relationship between depression during pregnancy and the risk of HDP, limited research has considered pre-pregnancy depression and the risk of HDP, especially among population-based samples.2 Additionally, taking into account pre-pregnancy anxiety, in addition to depression, is essential since they are highly comorbid with one another, especially among reproductive-aged women where the prevalence of depression and anxiety is thought to be double that of men of similar age.5

A prior community-based study in Michigan, called the Pregnancy Outcomes and Community Health (POUCH) study, revealed that women’s experiences of depression and/or anxiety before pregnancy, lifetime, or within the past year are associated with HDP, especially chronic hypertension and more severe HDP accompanied by preterm delivery.2 Our objective in this study was to discover if a population-based sample of at-risk women in Utah shows similar associations between pre-pregnancy depression and/or anxiety and HDP.

Methods

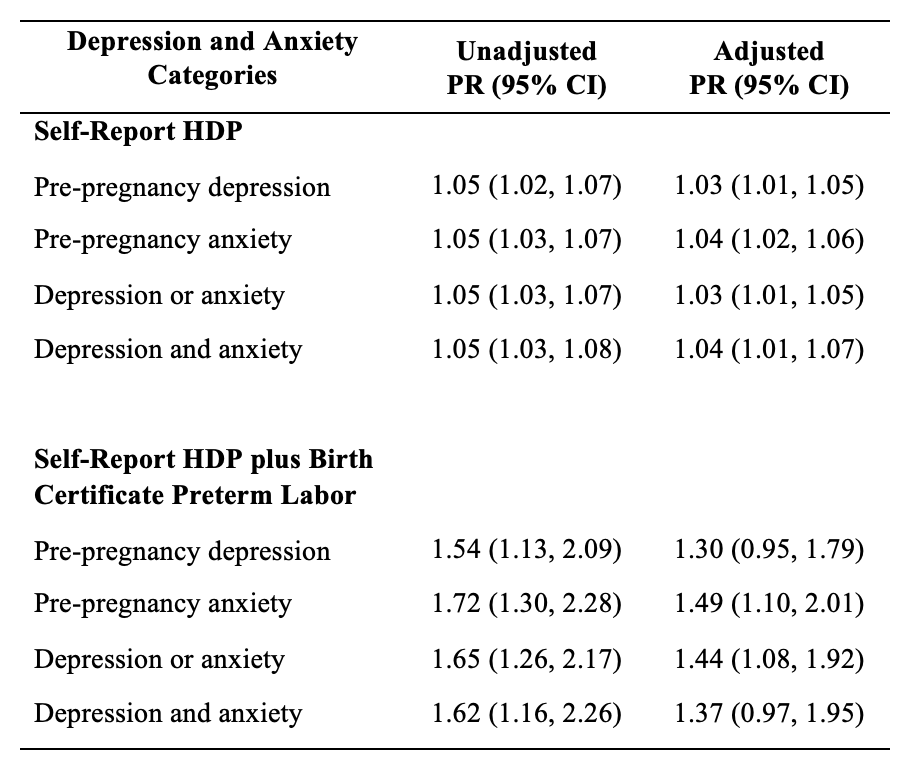

Study Participants and Questionnaire

The study population of interest was comprised of women who completed the Utah Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (UT-PRAMS) Phase 8 questionnaire between 2016 and 2020. The PRAMS is a surveillance project conducted with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and local health departments.6 The Utah PRAMS takes a random sample of approximately 200 new mothers monthly through statewide mailings and continuous telephone follow-ups for women who do not return the survey. The questionnaire is available in both English and Spanish. PRAMS utilizes state-specific stratified systematic sampling so that subpopulations of public health interest can be oversampled, such as mothers of low-birth-weight infants, those living in high-risk geographic areas, and racial/ethnic minority groups. Utah PRAMS stratifies by maternal educational status and birth weight. The expected response rate, according to the CDC, is 50% nationwide; the most recent weighted response rates for UT-PRAMS were 65%, 66%, 62%, 73%, and 67% for 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020, respectively.

Exposure

The exposure variable of interest is the presence of anxiety and depression before pregnancy. The presence of anxiety and depression was assessed based on the Phase 8 PRAMS self-report questionnaire. Women were asked, “During the 3 months before you got pregnant with your new baby, did you have any of the following conditions?” including “Depression” and “Anxiety,” requiring a yes/no answer. The exposure variable was assessed on four different levels: mothers who reported depression, anxiety, depression or anxiety, and depression and anxiety.

Outcome

This study’s primary outcome of interest was HDP, which was gathered via the Phase 8 PRAMS self-report questionnaire. Women were asked, “During your most recent pregnancy, did you have any of the following conditions,” including “high blood pressure (that started during this pregnancy), preeclampsia, or eclampsia?” requiring a yes/no answer. HDP was categorized as a dichotomous variable. While HDP was the primary outcome, we also evaluated a more severe HDP phenotype by combining self-report of HDP with preterm birth. Preterm birth, a continuous variable, was obtained from the birth certificate and was defined as <37 weeks gestational age.

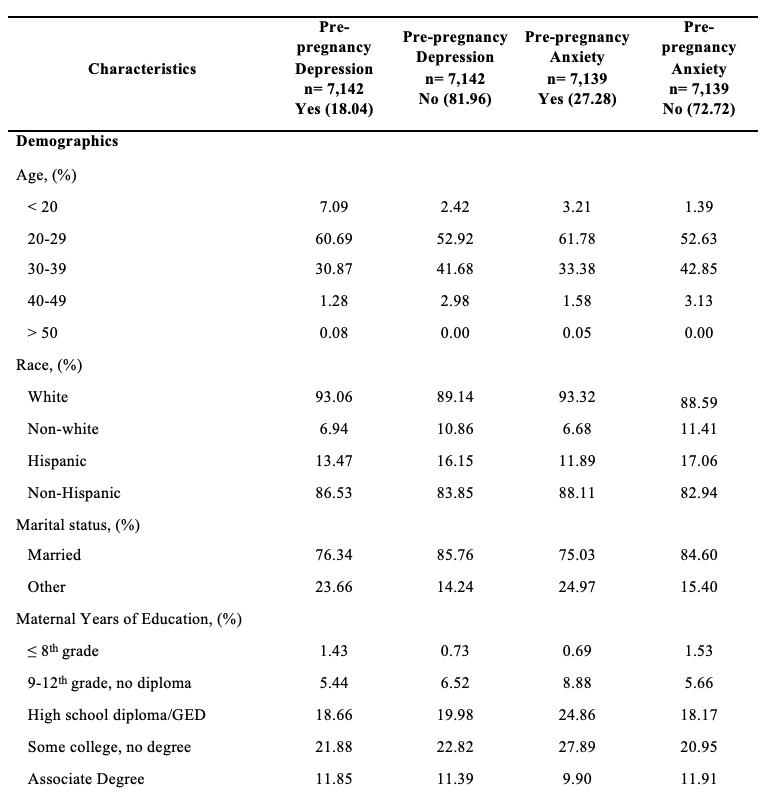

Covariates

Covariates included age, race, marital status, years of education, and BMI. Data on these variables was collected from the linked birth certificates. Maternal age was categorized into five categories: <20, 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, and 50+. Maternal race was categorized as Hispanic or not Hispanic and white or not white. Marriage was categorized by having ever been married or having never been married. Years of education were categorized by highest degree received (<8th grade, 9–12 grade no diploma, high school grad/ GED, some college no degree, associate degree, bachelors degree, masters degree, or doctorate). Pre-pregnancy BMI was categorized into four categories: below 18.5, normal (18.5–24.9), overweight (25.0–29.9, and obese (30+).

Covariates available from the PRAMS questionnaire included smoking status determined by the question “Have you smoked any cigarettes in the past 2 years?” (yes/no) and alcohol use determined by the question “Have you had any alcoholic drinks in the past 2 years? A drink is 1 glass of wine, wine cooler, can or bottle of beer, shot of liquor, or mixed drink” (yes/no). A previous diagnosis of PCOS was determined by asking, “Have you ever been told that you have Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome or PCOS by a doctor, nurse, or other health care worker?” (yes/no) and “During the 3 months before you got pregnant with your new baby, did you have any of the following health conditions?” including PCOS requiring a yes/no answer. Previous high blood pressure was also listed under the question, “During the 3 months before you got pregnant with your new baby, did you have any of the following health conditions?” (yes/no). Previous preterm birth was determined through the question, “Was the baby just before your new one born earlier than 3 weeks before his or her due date?” (yes/no).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses were used to explore the characteristics of the study population by pre-pregnancy depression and anxiety status. Relationships between pre-pregnancy depression and/or anxiety and HDP were assessed using robust Poisson distribution models to generate prevalence ratios (PRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We reported unadjusted and adjusted models. Key confounders were selected on the basis of previous knowledge as documented in the literature, including maternal age, race, Hispanic ethnicity, maternal education, pre-pregnancy BMI, drinking and smoking status in the last two years, and prior history of PCOS, preterm birth, or hypertension. Effect modification by pregnancy year and Hispanic ethnicity were tested using interaction terms within Poisson models (with Wald chi-square test for significance), with stratified results presented. Stata (version 17.0; StataCorp, College Station, TX) was used for the analyses.

Results

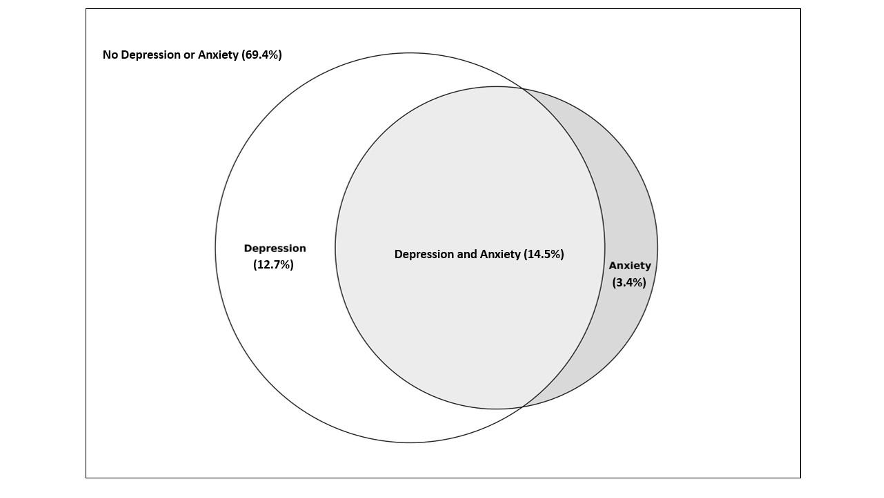

Of the women who participated in the 2016–2020 PRAMS questionnaire, 69.4% reported having no pre-pregnancy depression or anxiety, 14.5% had both pre-pregnancy depression and anxiety, 12.7% had anxiety, but no depression and 3.4% reported having depression but no anxiety (Figure 1). Women who experienced depression were more likely to be younger, white, have a previous preterm birth, smoke, drink, be obese, be less likely to be married, and have PCOS compared to those who do not experience depression (Table 1). There appeared to be no difference in the prevalence of previous high blood pressure (HBP) between women who reported depression and those who did not report depression. Women who reported having pre-pregnancy anxiety were more likely to be younger, white, have a previous preterm birth, smoke, drink, have PCOS, be obese, less likely to be married, and have previous HBP.

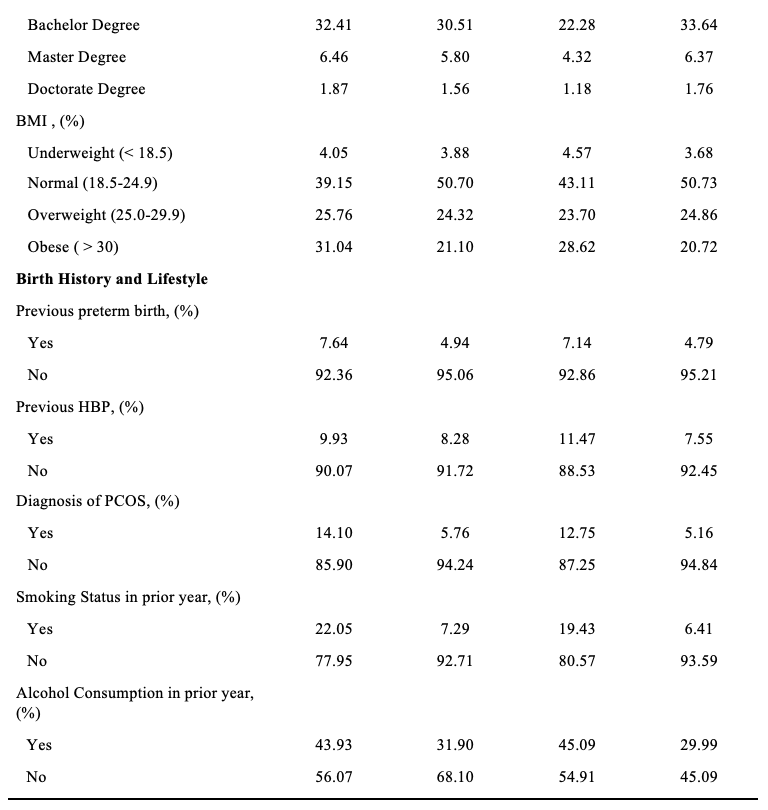

Women who reported pre-pregnancy depression and/or anxiety, compared to those who did not, had a 3–5% higher risk of having a hypertensive pregnancy after adjusting for maternal age, race, ethnicity, previous preterm birth, smoking status, prior alcohol consumption in the past two years, marital status, and pre-pregnancy BMI (Table 2). The prevalence increased to 30 to 49% when considering our defined “severe hypertensive pregnancy” that was accompanied by the preterm birth variable. Pre-pregnancy anxiety versus depression showed a greater association with having a severe hypertensive pregnancy, with an adjusted prevalence ratio of 1.49 (95% CI: 1.10, 2.01) for anxiety and 1.30 (95% CI: 0.95, 1.79) for depression. We found no evidence for effect modification by pregnancy year or Hispanic ethnicity (P=0.62 and 0.66 respectively).

Table 2: Unadjusted and adjusted prevalence ratios of HDP by self-reported hypertension during pregnancy and combined outcome of self-reported hypertension during pregnancy with preterm birth on birth record in Utah PRAMS (2016-2020), n=7,142 reflecting an estimated population of 231,242

Adjusted for maternal age, race, ethnicity, previous preterm birth, smoking status, prior alcohol consumption in the past two years, marital status, and BMI.

Discussion

In our study among Utah women participating in the PRAMs 2016–2020, we found that pre-pregnancy anxiety had a bigger effect on HDP than pre-pregnancy depression, with a nearly 50% increase in severe HDP among mothers who reported pre-pregnancy anxiety compared to those who did not have pre-pregnancy anxiety. These results slightly differed from observations made in the Michigan POUCH study, which found associations between both maternal chronic hypertension and pre-pregnancy depression/anxiety. While our study did not take into account the length of depression or anxiety symptoms or subcategorize HDP types (i.e., preeclampsia), the Michigan POUCH study made similar adjustments to maternal sociodemographic factors and found a larger association with pre-pregnancy anxiety than depression. Additional research is needed to differentiate risk between geographical areas.

Depression and HDP are thought to share a number of the same biological mechanisms.4 HDP is frequently linked to increased arterial stress and resistance in pregnant individuals.7 Research has demonstrated that individuals with depression also tend to exhibit increased arterial stiffness, which could potentially heighten their risk of developing HDP.4 Additionally, factors such as inflammation and oxidative stress have been shown to be associated with both depression and HDP, possibly creating a positive feedback loop between the two. 4 It is also important to note that some studies have shown that antidepressant and anxiolytic use in early pregnancy can contribute to HDP disorders and therefore must be considered when evaluating the association between depression and HDP.8

The strengths of this study include using a population-based sample that purposively includes at-risk mothers and a high response rate for sampling design. This study had several limitations as well. The cross-sectional study design limits our ability to infer causality between HDP and pre-depression and anxiety. In addition, while preterm birth does not necessarily mean the mother had HDP, the only cure for HDP is pregnancy or inducing the mother. It should be noted that we cannot be clear that the preterm birth was because of HDP.

There are multiple factors associated with HDP; this study supports that pre-pregnancy anxiety is a risk factor for HDP. The serious health problems caused by HDP affect both the mother and the baby across their lifespans. In order to reduce rates of HDP, the risk factors must be reduced. However, not all the associated factors are easy to address. Among the multiple factors associated with HDP, pre-pregnancy anxiety, and depression are factors that we can treat and intervene to reduce risk. This knowledge can lead to the development of programs and treatments focusing on pre-pregnancy anxiety and depression and could have implications for future treatments.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Data were provided by the Utah Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), a project of the Utah Department of Health (UDOH), the Office of Vital Records and Health Statistics of the UDOH, and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of the United States Health and Human Services Department. This report does not represent the official views of the CDC, Utah Department of Health, or the NIH.

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank the contributions of Dr. Karen Schliep, Will Burnett, and Yunah Cho.

References

- Pearlstein T. Depression during Pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. Jul 2015;29(5):754-64. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.04.004

- Thombre MK, Talge NM, Holzman C. Association between pre-pregnancy depression/anxiety symptoms and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. J Womens Health (Larchmt). Mar 2015;24(3):228-36. doi:10.1089/jwh.2014.4902

- Ford ND, Cox S, Ko JY, et al. Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy and mortality at delivery hospitalization—United States, 2017–2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2022;71(17):585.

- Yuan M, Bedell S, de Vrijer B, Eastabrook G, Frisbee JC, Frisbee SJ. Highlighting the Mechanistic Relationship Between Perinatal Depression and Preeclampsia: A Scoping Review. Womens Health Rep (New Rochelle). 2022;3(1):850-866. doi:10.1089/whr.2022.0062

- Kalin NH. The Critical Relationship Between Anxiety and Depression. Am J Psychiatry. May 1 2020;177(5):365-367. doi:10.1176/app.ajp.2020.20030305

- Shulman HB, D’Angelo DV, Harrison L, Smith RA, Warner L. The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS): Overview of Design and Methodology. Am J Public Health. Oct 2018;108(10):1305-1313. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2018.304563

- Estensen, M.-E., Remme, E. W., Grindheim, G., Smiseth, O. A., Segers, P., Henriksen, T., & Aakhus, S. (2013, April). Increased arterial stiffness in pre-eclamptic pregnancy at term and early and late postpartum: A combined echnocardiographic and tonometric study. American Journal of Hypertension, 26(4), 549-556. DOI: 10.1093/ajh/hps067

- Bernard, N., Forest, J.-C., Tarabulsy, G. M., Bujold, E., Bouvier, D., & Giguere, Y. (2019). Use of antidepressants and anxiolytics in early pregnancy and the risk of preeclampsia and gestational hypertension: a prospective study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 19(146). DOI: 10.1186/s12884-019-2285-8

Citation

Lee J, Codd N, and Morgan H. (2024). Prenatal Depression and Anxiety and Risk of Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy: Findings from the Utah Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring Survey (2016–2020). Utah Women’s Health Review. doi: 10.26054/d-b4jk-797f

Understanding trends in shared reading to inform targeted literacy interventions in early childhood: A data snapshot

Background

Evidence linking arts and health has been mounting, and the World Health Organization (WHO) compiled this evidence in a 2019 report.1 The report explains how the arts combine health-promoting factors (e.g., cognitive stimulation) with an intrinsic desire to experience beauty or creativity. Literature is one artistic medium that can support health and well-being. For example, reading a good book evokes empathy, reduces stress, and makes the brain work hard to understand language, recall information, and imagine written descriptions. Readers may also encounter and engage with themes of health.1

Engaging with literature is especially important during early childhood. Early childhood literacy (ECL) is vital in strengthening future intellectual health – not just academic or health-related knowledge but creativity, curiosity, critical thinking, and problem-solving.2 Shared reading is one example of an ECL-promoting activity. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) encourages families to read with their children as often as possible during the first three years of life as an effective way to strengthen the parent-child relationship and promote brain development around language and reasoning.3 The AAP recommends shared reading up to age three because this is the most intensive period of brain development. Additionally, continued shared reading up to age five is important for school readiness and future educational attainment; children who have consistent shared reading experiences from ages 2 to 5 are more likely to succeed in grade school.4

Further, educational attainment is strongly associated with future health at the population-level.5 The cognitive skills and background knowledge developed during school years help adults choose, for example, healthy lifestyles or understand medication regimens. Individuals who did not finish high school are also less likely to have health insurance.6 Further, education is influenced by other social determinants of health, including income. A study exploring how time in poverty influences high school graduation explained that proficient readers from poor backgrounds are less likely to finish high school than their less proficient counterparts who have never experienced poverty. Additionally, single-parent households – the majority of which are headed by single mothers – are more likely to live in poverty relative to married households (27 vs 8 percent), as well have reduced access to social or economic resources.7,8 However, one study showed that the benefits of shared reading were more strongly associated with educational outcomes (e.g., vocabulary knowledge, future educational success) in low- and middle-income households compared to high-income households.4

Recognizing the importance of reading in early childhood on social determinants of health like education, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) established Healthy People (HP) 2020 and 2030 goals to increase the number of children aged 0-5 whose families read to them frequently. The 2020 goal is the more rigorous of the two, aiming to increase the percentage of families reading with their young child every day to a target of 52.6% of (about 11.8 million) children.9

By understanding how trends in shared reading frequency have changed over time, those invested in early childhood development can make more informed decisions about strategy or resource allocation to reach families who need the most support. This data snapshot reports on the percentage of families in the US who met the HP 2020 target for shared reading, stratifies trends by income and household composition, and discusses recommendations for interventions that increase frequent engagement with literature through shared reading.

Data Snapshot

Data

The Health Services and Resources Administration (HRSA) directs the National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH), and single- and multi-year data from 2016 to 2022 are publicly available in a searchable online database.10 Single-year survey data for the NSCH question “During the past week, how many days did you or a family member read to this child, age 0-5 years?” informs the HP 2020 goal for shared reading. Income strata are the upper (greater than or equal to 400%) and lower (less than 100%) household Federal Poverty Levels (FPL). Household composition strata are single-parent households (not differentiated by parent sex after 2016) and married households. The error bars show the margin of error for each year’s sample. Sample sizes for each year are in Table 1.

| Table 1. Sample Sizes | |||||

| Year | Total sample | <100% FPL | >400% FPL | Single parent | Married |

| 2016 | 6623 | 491 | 3330 | 403 | 5588 |

| 2017 | 2904 | 288 | 1366 | 219 | 2401 |

| 2018 | 3719 | 316 | 1883 | 451 | 2938 |

| 2019 | 3532 | 276 | 1778 | 342 | 2860 |

| 2020 | 5484 | 453 | 2795 | 548 | 4472 |

| 2021 | 9940 | 757 | 5198 | 939 | 8160 |

| 2022 | 9526 | 708 | 5147 | 918 | 7765 |

Results

Figure 1a shows the percentage of families reading to their children daily, stratified by the lowest and highest income groups. Compared to the benchmark, parents in the highest income category met the target percentage (52.6%) around 2019 and continued to improve until 2022. Among the lowest income group, the percentage of families reading daily to their children was lower than the average across all years and decreased from around 30% in 2016 to around 25% in 2022. The average disparity between high- and low-income families was 26%.

Figure 1b shows the percentage of families reading to their children daily, stratified by household composition. Neither type of household met the benchmark for daily shared reading. Married households increased shared reading from around 40% in 2016 to about 45% in 2022. Meanwhile, shared reading frequency among single-parent households decreased over time, from over 30% in 2016 to around 27% in 2022. The average disparity between married and single-parent households was 15%.

Overall, low-income households, which are also more likely to be single-parent and specifically single-mother homes, have lower frequencies of daily shared reading compared to higher income or married households, and this disparity has been stable over time. Trends for low-income compared to single-parent households over time are almost identical, highlighting the overlap between low-income and single-parent families. Low-income and single-parent families should have the same opportunities to support early childhood literacy as wealthier families. Given the strong influence of education on future health, these trends underscore a need for innovative shared reading interventions that consider factors like income and household composition.

Evidence-based shared reading interventions

A popular intervention to increase shared reading is book gifting, where families receive age-appropriate reading materials and sometimes educational materials for parents on the benefits of reading in early childhood. One of the largest book gifting programs is Reach Out and Read (ROR) – providing over 4.4 million children with reading materials through well-child visits each year.11 Nationally, ROR reaches a large population of low-income families. However, using a social-ecological approach might reach more families.11,12(p1) Table 2 summarizes book gifting interventions situated in multiple settings that positively affected shared reading and longer-term outcomes like school readiness.

Recommendations to promote shared reading in Utah

Utah has a higher percentage of children under 5 in the population (6.9%) compared to the national average (5.6%).16,17 To reach more children from low-income households, state and local policymakers could allocate both political and financial resources to develop or enhance shared reading programs in settings beyond the clinic. To increase access to materials for shared reading for single-mothers, developing or enhancing a program modeled after Little by Little (Table 1) could improve school readiness for some of the 20,000+ children participating in WIC across Utah.18 This option may be particularly well-suited to reach single-mother households who attend WIC programming. Additionally, an intervention like Tender Shoots (Table 1) could teach parents how to improve their shared reading skills and be involved in their child’s learning; Utah already has local infrastructure to support similar community-based programs, namely public libraries and Early Head Start preschools.

Currently, Utah does not monitor data on shared reading. To better understand the unique contexts of Utah families, the NCHS question that informs HP 2020 could be administered through the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey. This phone-based survey administered through the Department of Health and Human Services – Health Survey Office collects data on many behavioral, social, and demographic variables.19 Participants who indicate they live with children between 0-5 could be asked how often they or another family member read with the child.

Conclusion

Utilizing the arts as an enjoyable pathway to improved health outcomes can begin in early childhood through ECL-promoting activities like shared reading. Shared reading strengthens intellectual health and helps build a foundation for continued educational attainment. However, data on shared reading frequency show that low-income and single-parent households participate in shared reading less frequently than higher-income or married households. More, this disparity persists over time. These trends underscore a need for shared reading interventions that consider environmental and social factors. Local and state policymakers can advocate for and direct financial resources toward ECL-promoting programs that set young children up for future educational attainment and better health.

References

1. Daisy Fancourt, Saoirse Finn. What Is the Evidence on the Role of the Arts in Improving Health and Wellbeing? A Scoping Review. World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; 2019:9-28.

2. Harvard University Center for Wellness and Health Promotion. Intellectual. Your Wellbeing. Published 2024. Accessed March 11, 2024. https://wellness.huhs.harvard.edu/intellectual

3. Early Literacy. Accessed February 11, 2024. https://www.aap.org/en/patient-care/early-childhood/early-childhood-health-and-development/early-literacy/

4. Shahaeian A, Wang C, Tucker-Drob E, Geiger V, Bus AG, Harrison LJ. Early Shared Reading, Socioeconomic Status, and Children’s Cognitive and School Competencies: Six Years of Longitudinal Evidence. Sci Stud Read. 2018;22(6):485-502. doi:10.1080/10888438.2018.1482901

5. Marmot MG. Understanding Social Inequalities in Health. Perspect Biol Med. 2003;46(3):S9-S23.

6. US Census Bureau. Differences in Uninsured Rates by Race and Ethnicity Persist Even Among Those With Higher Educational Attainment. Census.gov. Published March 8, 2023. Accessed June 28, 2024. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2023/03/education-and-racial-disparities-in-health-insurance-coverage.html

7. Hernandez DJ. Double Jeopardy: How Third-Grade Reading Skills and Poverty Influence High School Graduation. Annie E; 2011. Accessed February 11, 2024. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED518818

8. Livingston G. The Changing Profile of Unmarried Parents. Pew Research Center. Published April 25, 2018. Accessed June 28, 2024. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2018/04/25/the-changing-profile-of-unmarried-parents/

9. US Department of Health and Human Services. Increase the proportion of parents who read to their child every day. Search the Data – Healthy People 2020. Published 2021. Accessed February 25, 2024. https://wayback.archive-it.org/5774/20220414213024/https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/data-search/Search-the-Data?nid=4363

10. Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health. NSCH Interactive Data Query (2016 – present). Explore the data. Published 2022. Accessed February 25, 2024. https://www.childhealthdata.org/browse/survey#52_1_3028

11. Reach Out and Read. Our Impact. Why We Matter. Published 2023. Accessed March 11, 2024. https://reachoutandread.org/why-we-matter/our-impact/

12. Donna McCloskey, Sergio Aguilar-Gaxiola. Chapter 1: Models and Frameworks for the Practice of Community Engagement – The Social Ecological Model of Health.; 2018:20-23. Accessed March 21, 2024. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pce_models.html

13. Connor Garbe M, Bond SL, Boulware C, et al. The Effect of Exposure to Reach Out and Read on Shared Reading Behaviors. Acad Pediatr. 2023;23(8):1598-1604. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2023.06.030

14. Whaley SE, Jiang L, Gomez J, Jenks E. Literacy Promotion for Families Participating in the Women, Infants and Children Program. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):454-461. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-3572

15. Timperley S, Schaughency E, Riordan J, Carroll J, Das S, Reese E. Tender Shoots: Effects of a Preschool Shared Book Reading Preventive Intervention on Parent–Child Reading and Parents’ Involvement in the First Year of School. School Ment Health. 2022;14(2):238-253. doi:10.1007/s12310-022-09505-6

16. U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Utah. Accessed March 18, 2024. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/UT/PST045223

17. U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: United States. Accessed March 18, 2024. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045222

18. WIC Data Table. Food and Nutrition Service. Published 2022. Accessed March 21, 2024. https://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/wic-program 19. Utah Department of Health and Human Services. Health Survey Program | Office of Public Health Assessment. Utah Department of Health and Human Services. Accessed March 21, 2024. https://healthassessment.utah.gov/health-survey-program

Citation

Gardner E. (2024). Understanding trends in shared reading to inform targeted literacy interventions in early childhood: A data snapshot. Utah Women’s Health Review. doi: 10.26054/d-0fnw-k39a

Characteristics Associated with Miscarriages in Utah Nail Technicians

Abstract

Objective: Previous studies suggest possible worker over-exposure to hazardous chemicals in nail salons. The purpose of this study was to identify exposure characteristics among nail technicians that might be associated with adverse reproductive health outcomes.

Methods: Using a cross-sectional design, 937 nail technicians licensed in Utah were invited to complete an online questionnaire regarding general and reproductive health, working career, and common health and safety practices. The relationship between nail technicians who had been pregnant and experienced at least one miscarriage was compared to nail technicians with a history of pregnancy but no miscarriages to identify potentially relevant characteristics.

Results: Ninety (90) nail technicians participated in the survey. Of those who reported ever having been pregnant, 36% (17/47) reported having had at least one miscarriage. Those who had experienced a miscarriage were significantly younger (mean ~10 years) than those who had been pregnant but did not report a history of miscarriage. Although those who had a history of miscarriage were less likely to use exposure control equipment, that difference was not statistically significant.

Conclusion: High miscarriage rates in participants indicate that further study is needed. Since selection bias may have affected who chose to complete the survey, a larger sample size and additional community engagement is needed.

Implications: Future research should seek to obtain a higher participation rate, quantify chemical exposures directly, examine health symptoms, and understand what exposure control measures are most effective. With continued research, the hope is that technicians can see improved health and safety over their working careers.

Introduction

Occupational exposures experienced by cosmetologists are associated with a significantly increased risk of adverse reproductive health effects, including infertility, reductions in fetal growth, fetal death, and preterm delivery.1-4 Specifically, chemicals found in nail products (e.g., formaldehyde, toluene, dibutyl phthalate, etc) have been shown to result in increases in fertility problems or pregnancy loss,5,6 congenital birth defects,7 effects similar to Fetal Alcohol Syndrome,8,9 and possible epigenetic risks transmitted to later generations.10 Most cosmetologists are reproductive-age women, with nail technicians being an especially vulnerable population. A large percentage of nail technicians are racial/ethnic minorities, with one estimate for the US indicating 72% are Vietnamese,11 and many experience inadequate pay and personal protections.12 With approximately 163,600 manicurists and pedicurists employed today, and a projected growth of 22% by 2031, additional research is needed to determine what associations, if any, exist between hazardous chemical exposure and adverse reproductive health outcomes among nail technicians.13

Previous studies examining workplace exposures in nail salons are limited, but literature that is available points to a concerning trend towards overexposure to hazardous chemicals, including acetone, butyl acetate, ethyl acetate, ethyl methacrylate (EMA), formaldehyde, isopropyl acetate, methacrylic acid, methyl methacrylate (MMA), and phthalates.14-19 Air monitoring of nail salons within the state of Utah found formaldehyde concentrations were above the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Recommended Exposure Limit (REL) in 58% of establishments studied, with MMA (banned in Utah) found in a majority of establishments as well.17 Exposure controls (engineering, administrative practices, and personal protective equipment) are a key to reducing/preventing exposure, but their use in practice appears to be lacking.20,21 It is well understood that some exposure controls that remove a chemical before it can reach workers (e.g., local ventilation) are more effective than controls that rely on workers to use them properly (e.g., masks).5 Therefore, this study sought to investigate the protective practices for exposure, and reproductive health outcomes of nail technicians.

Methods

This cross-sectional study surveyed nail technicians who are currently or formerly licensed in the state of Utah via an online questionnaire regarding general and reproductive health, working career, as well as common health and safety practices. The study was reviewed by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board (IRB) and considered exempt.

Participants

The list of all nail technicians who are currently or formerly licensed in Utah (as of October 2020) was obtained from the Utah Department of Occupational and Professional Licensing (DOPL) (n=10,109). The information obtained included the following: full name, address, date of license, date of license expiration, phone number, and email address (optional). The study included nail technicians with both active and expired licenses to reduce the risk of bias linked to the healthy worker effect; i.e. this method included nail technicians who have potentially retired, quit working due to health complications, or left the industry.

Out of all 10,109 nail technicians formerly or currently licensed with the state, a computerized random number generator was used to randomly select a subset of 1,000 to invite to complete the questionnaire. The questionnaire was then distributed via two means: first, a postcard listing the URL of the survey was sent to the mailing address of each participant. For those participants with email addresses on file (n=710), a total of three email reminders with the survey address were also sent. Potential participants were incentivized to complete the survey by an entry into a gift card drawing.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was administered using SurveyMonkey, a mobile-friendly platform that was easily accessible on either a computer or a smartphone. SurveyMonkey was also selected due to the ability to offer participants their choice of preferred language between Vietnamese and English. The survey was translated into Vietnamese by a certified translator and verified by a native-speaker who works in healthcare. The survey was conducted between November 2020 and January 2021.

The questionnaire was designed to be completed in approximately 20 minutes and is a modified version of a previously used tool for assessing lifetime reproductive outcomes.22 The survey consisted of questions regarding general health, menstrual history, sexual history, becoming pregnant/conceiving, pregnancy outcomes, fertility, fertility treatment, and demographic information. The survey also contained questions regarding work history and the use of exposure controls such as local ventilation or personal protective equipment (PPE) during work. A question was also included asking participants to comment and evaluate the survey with the aim of improving future iterations.

If participants did not wish to answer any one question, they could do either by skipping the question or answering with “Prefer not to answer.” To prevent unnecessary confusion, the online survey was designed with skip logic; for example, if a participant answered “Never” to the question “How many times have you been pregnant?” the survey would automatically skip them from answering questions pertaining to pregnancies and live births. Therefore, the number eligible to respond varied for each question. If participants failed to answer any of the questions pertaining to the variables included in the statistical analysis (number of miscarriages, years worked, hours worked per week, smoking status, drinking status, age, race, and household income), they were excluded from further analysis (i.e., complete case analysis).

Responses were submitted without personally identifiable information. IP address tracking was also turned off to further remove any identifying information. Responses from the questionnaire were stored and maintained in Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington) and statistical analysis was performed using SAS statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Data Analysis

Respondents were grouped based on their history of pregnancy and/or miscarriage, including (1) never been pregnant, (2) prior pregnancy but no miscarriages, and (3) at least one miscarriage, i.e., analysis by outcome group (case control). Due to the small sample size, fisher’s exact test was used to compare the groups with prior pregnancy (with and without miscarriage) across the various categories of interest. For continuous variables a t-test was used to compare group means between the miscarriage vs non-miscarriage groups. When there were unequal variances, a Welch test was performed. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical software.

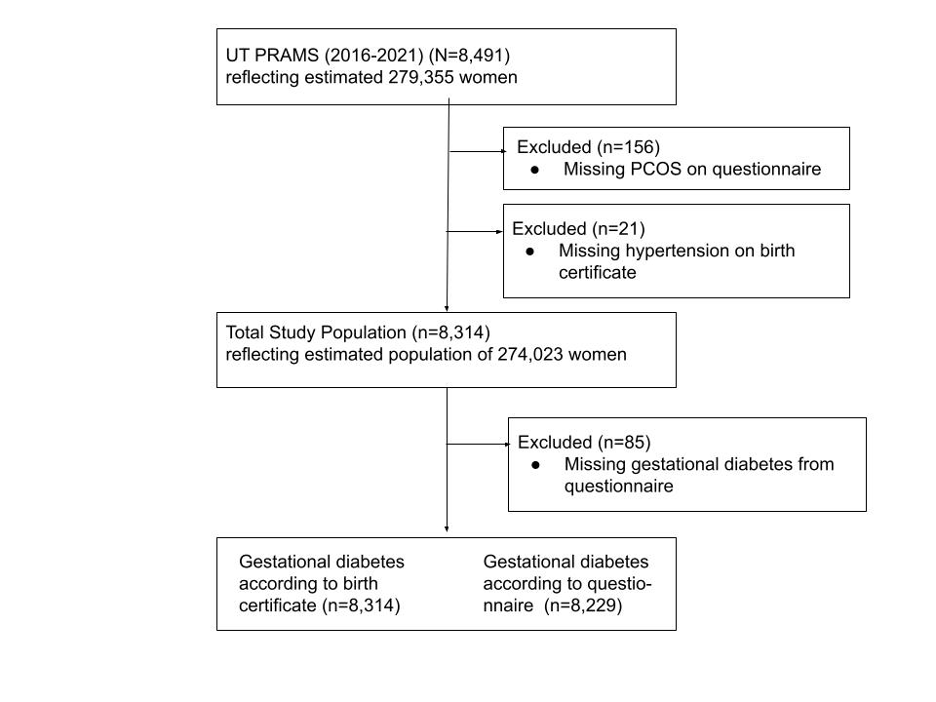

There is limited research in the area of nail salon exposure controls, so a novel approach to analyzing those data is presented here. For this, a protective equipment usage score was developed specially for this work and was calculated for each respondent, as shown in Figure 1. For each type of control equipment used, a different value was given to each, based on the potential control it provided, including: a score of 2 for a loose mask (e.g., surgical mask) and/or a large fan (i.e., room fan), a score of 3 for gloves and/or a small fan (i.e., personal/table fan), a score of 4 for a snug mask (e.g., N95) and/or a ventilated table, and a score of 5 for a cartridge respirator and/or a local exhaust ventilation hood. These scores were based on the hierarchy of controls, such that more protective engineering controls (e.g., ventilation) were given higher priority than personal protective equipment (e.g., loose mask).5 As an additional variable, the frequency of use for each piece of equipment was incorporated into a “weighted score”. In this case, “Never” = 0, “Several clients per year” = 0.1, “Several clients per month” = 1.2, “Several clients per week” = 4.8, and “Every client” = 10. For example, somebody who used a loose mask for every client would get 20 pts, and if that person also used a ventilated table for several clients per week, they would get an additional 19.2 pts for a total of 39.2 pts.

Results

Overall Respondent Characteristics

Out of the 1,000 randomly chosen participants who were mailed a postcard, 101 were returned as undeliverable. Out of the 710 emails sent, 38 emails were bounced back on all three attempts. Ultimately, 63 participants either did not have emails on file, had incorrect emails, or had undeliverable postcards; a total of 937 participants either received an email or a postcard inviting them to participate (Figure 2).

After 2 months, 90 nail technicians responded to the survey (response rate of 9.6%). The mean proportion of the survey that was completed for each participant was 82%, with a mean completion time of approximately 12 minutes. A total of 85 (94%) participants submitted the survey in English and 5 (6%) submitted the survey in Vietnamese. However, only 68 people had usable information regarding the birth related outcomes. Nine (9) respondents did not answer those questions. A further thirteen (13) provided conflicting answers, for example the number of miscarriages was greater than the number of pregnancies. In those cases where the answers did not match, the data were not included in the analysis. The primary analysis included here is for those with a history of pregnancy, broken out by those with (n=17) and without (n=30) a history of miscarriage. Summary data for all respondents and those who had never been pregnant are provided in supplemental material (Table S1 and S2).

The mean age of registered nail technicians who responded was 33.6 years old. Participants were predominantly White (63.3%) and Vietnamese (13.3%). The mean number of years worked as a nail technician was 7.8 years with a median of 5 years. The mean number of hours worked per week for nail technicians was 25.5 hours. 36% (n=17) of participants who had been pregnant (n=47) experienced at least one miscarriage in their life. About half, 48.9% (n=44) of nail technicians reported having received training on how to reduce their exposures to chemicals at work. It was found that 65.6% of nail technicians who responded reported having a monthly period, 28.9% reported adult acne, 10% reported thyroid disease, 11.1% reported high blood pressure, and 3.3% reported a cancer diagnosis. Participants indicated relatively healthy habits: 81% of the participants were non-smokers and 71% do not drink any alcohol regularly (see Table S1). The overall health of the study population may be reflected in Utah’s wider population, as Utah was ranked the seventh healthiest state by the United Health Foundation in 2022, and has very low rates for use of tobacco or alcohol.23

Comparison of Respondents with and without Miscarriages

Respondents who reported having at least one miscarriage were on average younger by approximately 10 years (p=0.004) (see Table 1). They were also more likely to be single compared to the non-miscarriage and never pregnant groups (25% vs 11.5%), although that difference was not statistically significant (p=0.128). The miscarriage group was more likely to have a BMI >30 (52.9%) compared to the non-miscarriage group (30%), but that relationship was also not statistically significant.

In terms of their work, the miscarriage group had less experience than the non-miscarriage group (median of 2 years vs 9 years; p=0.017) and saw fewer clients per day (median = 2 vs 4; p=0.03). The miscarriage group was also more likely to work <20 hours per week compared to the non-miscarriage group (81.3% vs 44.8%), which was not quite a significant difference (p=0.063). These variables are likely related to the fact that the miscarriage group was much younger on average than the non-miscarriage group.

The clinical characteristics for the miscarriage and non-miscarriage groups are shown in Table 2. The non-miscarriage group reported a median number of live births of 2 compared to the miscarriage group, with a median of 1. Again, this could be explained by the age difference between these groups. It is also interesting to note that the miscarriage group reported 13.3% rate of low birth weight babies, compared to 7.1% in the non-miscarriage group. Overall, there were no statistically significant differences between the miscarriage group and the non-miscarriage group for the clinical characteristics of interest.

The calculated protective equipment scores and the frequency of use for different control methods are shown in Table 3. The median weighted protective equipment usage score for nail technicians with no history of miscarriage was 43.5, compared to a median of 26.2 for those with at least one miscarriage. This corresponds to fewer types of protective equipment used and/or less frequent use of any such equipment for those with a miscarriage, although this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.837). Nail technicians, on average, used ventilated downdraft tables the most (34.5% in the non-miscarriage group and 25% in the miscarriage group used them for every client), followed by a loose mask (30% use for every client, n=27). The least used control method was half-face cartridge respirators, with 100% of respondents with a history of pregnancy having never used one. In both groups, more than half of respondents (62.1% of non-miscarriage group and 68.8% of the miscarriage group) reported never using gloves when performing their work.

Discussion

This study offers fresh insight into an understudied and potentially vulnerable occupational population. Based on the limited use of protective equipment, there exists a potential for high chemical exposures and thereby pregnancy complications. It also provides insight into contacting nail technicians and overcoming barriers associated with the typical nail-salon (i.e., smaller, family-run, non-English speakers), as well as a novel way to quantify the use of exposure control strategies.

The small sample size prevents definitive conclusions, and limits reliance on statistical significance, but there are several findings that may inform future research. One finding of concern was that 36% of respondents who had been pregnant reported having experienced at least one miscarriage, a number that seems high compared to the ~10-20% of all known pregnancies in the general population that end in miscarriage24; about 25% of women experience a miscarriage in their lifetime.25 The percentage found here is also higher than a previous study of nail technicians on the East Coast of the United States which found 15.6% of nail technicians who have been pregnant experienced at least one miscarriage.26 It is possible that selection bias, such that the respondents do not reflect the overall population of interest based on self-selection into the study, may over-estimate the miscarriage rate. Additionally, the <10% response rate may also affect interpretation of this finding, but additional research is still warranted. A higher response rate may help confirm if miscarriages are in fact more prevalent in this population and whether the variables that were found to be significant here remain important. The known reproductive toxicity of many of the chemicals in nail products5-10 also supports this association, but further epidemiological research is clearly warranted in this area.