Table of Contents

Abstract

Objectives: Depression during pregnancy has recently been found to affect the risk of hypertensive pregnancy disorders. However, few studies have looked at the effect of having depression or anxiety prior to pregnancy and its effects on hypertensive pregnancy disorders (HDP). This study aims to analyze a population-based sample of at-risk pregnant women in Utah using the Utah Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (UT-PRAMS) to discover whether there is an association between pre-pregnancy depression/anxiety and HDP.

Methods: The study analyzed responses from the Utah Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (UT-PRAMS) Phase 8 questionnaire between 2016 and 2020 using descriptive statistics and robust Poisson distribution models.

Results: Women who reported pre-pregnancy depression and/or anxiety, compared to those who did not, had a 3–5% higher risk of having an HDP after adjusting for important sociodemographic, reproductive history, and lifestyle factors. The risk increased to 30–49% when using our more severe HDP definition, as used in prior studies, which combined self-report of HDP and birth-certificate verified preterm births.

Conclusions and Implications: These results slightly differ from the observations made in the Pregnancy Outcomes and Community Health (POUCH) study. While our study did not take into account the length of depression or anxiety symptoms or subcategorize HDP types (i.e., preeclampsia), this study made similar adjustments to maternal sociodemographic factors and found a more significant association with pre-pregnancy anxiety than depression.

Introduction

Depression during pregnancy is thought to impact 10–20% of US women. 1 It is a common concern that has been associated with several adverse pregnancy complications, including hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP).2 HDP, such as preeclampsia, eclampsia, and gestational hypertension, affect approximately one in seven delivery hospitalizations and are conditions that can cause serious health problems for both the mother and the baby across the lifespan.3

Cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors, including inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction, are expected to affect both depression and HDP, supporting common contributing mechanisms for both conditions.4 Despite the growing evidence of the relationship between depression during pregnancy and the risk of HDP, limited research has considered pre-pregnancy depression and the risk of HDP, especially among population-based samples.2 Additionally, taking into account pre-pregnancy anxiety, in addition to depression, is essential since they are highly comorbid with one another, especially among reproductive-aged women where the prevalence of depression and anxiety is thought to be double that of men of similar age.5

A prior community-based study in Michigan, called the Pregnancy Outcomes and Community Health (POUCH) study, revealed that women’s experiences of depression and/or anxiety before pregnancy, lifetime, or within the past year are associated with HDP, especially chronic hypertension and more severe HDP accompanied by preterm delivery.2 Our objective in this study was to discover if a population-based sample of at-risk women in Utah shows similar associations between pre-pregnancy depression and/or anxiety and HDP.

Methods

Study Participants and Questionnaire

The study population of interest was comprised of women who completed the Utah Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (UT-PRAMS) Phase 8 questionnaire between 2016 and 2020. The PRAMS is a surveillance project conducted with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and local health departments.6 The Utah PRAMS takes a random sample of approximately 200 new mothers monthly through statewide mailings and continuous telephone follow-ups for women who do not return the survey. The questionnaire is available in both English and Spanish. PRAMS utilizes state-specific stratified systematic sampling so that subpopulations of public health interest can be oversampled, such as mothers of low-birth-weight infants, those living in high-risk geographic areas, and racial/ethnic minority groups. Utah PRAMS stratifies by maternal educational status and birth weight. The expected response rate, according to the CDC, is 50% nationwide; the most recent weighted response rates for UT-PRAMS were 65%, 66%, 62%, 73%, and 67% for 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020, respectively.

Exposure

The exposure variable of interest is the presence of anxiety and depression before pregnancy. The presence of anxiety and depression was assessed based on the Phase 8 PRAMS self-report questionnaire. Women were asked, “During the 3 months before you got pregnant with your new baby, did you have any of the following conditions?” including “Depression” and “Anxiety,” requiring a yes/no answer. The exposure variable was assessed on four different levels: mothers who reported depression, anxiety, depression or anxiety, and depression and anxiety.

Outcome

This study’s primary outcome of interest was HDP, which was gathered via the Phase 8 PRAMS self-report questionnaire. Women were asked, “During your most recent pregnancy, did you have any of the following conditions,” including “high blood pressure (that started during this pregnancy), preeclampsia, or eclampsia?” requiring a yes/no answer. HDP was categorized as a dichotomous variable. While HDP was the primary outcome, we also evaluated a more severe HDP phenotype by combining self-report of HDP with preterm birth. Preterm birth, a continuous variable, was obtained from the birth certificate and was defined as <37 weeks gestational age.

Covariates

Covariates included age, race, marital status, years of education, and BMI. Data on these variables was collected from the linked birth certificates. Maternal age was categorized into five categories: <20, 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, and 50+. Maternal race was categorized as Hispanic or not Hispanic and white or not white. Marriage was categorized by having ever been married or having never been married. Years of education were categorized by highest degree received (<8th grade, 9–12 grade no diploma, high school grad/ GED, some college no degree, associate degree, bachelors degree, masters degree, or doctorate). Pre-pregnancy BMI was categorized into four categories: below 18.5, normal (18.5–24.9), overweight (25.0–29.9, and obese (30+).

Covariates available from the PRAMS questionnaire included smoking status determined by the question “Have you smoked any cigarettes in the past 2 years?” (yes/no) and alcohol use determined by the question “Have you had any alcoholic drinks in the past 2 years? A drink is 1 glass of wine, wine cooler, can or bottle of beer, shot of liquor, or mixed drink” (yes/no). A previous diagnosis of PCOS was determined by asking, “Have you ever been told that you have Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome or PCOS by a doctor, nurse, or other health care worker?” (yes/no) and “During the 3 months before you got pregnant with your new baby, did you have any of the following health conditions?” including PCOS requiring a yes/no answer. Previous high blood pressure was also listed under the question, “During the 3 months before you got pregnant with your new baby, did you have any of the following health conditions?” (yes/no). Previous preterm birth was determined through the question, “Was the baby just before your new one born earlier than 3 weeks before his or her due date?” (yes/no).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses were used to explore the characteristics of the study population by pre-pregnancy depression and anxiety status. Relationships between pre-pregnancy depression and/or anxiety and HDP were assessed using robust Poisson distribution models to generate prevalence ratios (PRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We reported unadjusted and adjusted models. Key confounders were selected on the basis of previous knowledge as documented in the literature, including maternal age, race, Hispanic ethnicity, maternal education, pre-pregnancy BMI, drinking and smoking status in the last two years, and prior history of PCOS, preterm birth, or hypertension. Effect modification by pregnancy year and Hispanic ethnicity were tested using interaction terms within Poisson models (with Wald chi-square test for significance), with stratified results presented. Stata (version 17.0; StataCorp, College Station, TX) was used for the analyses.

Results

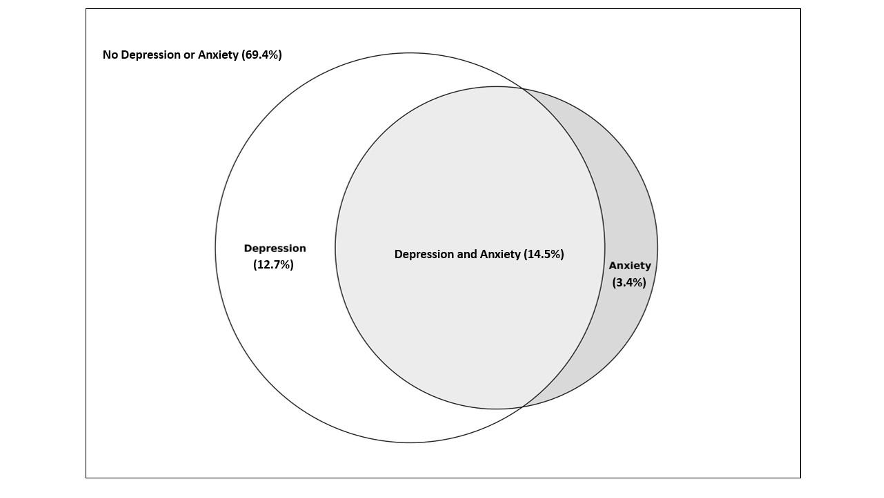

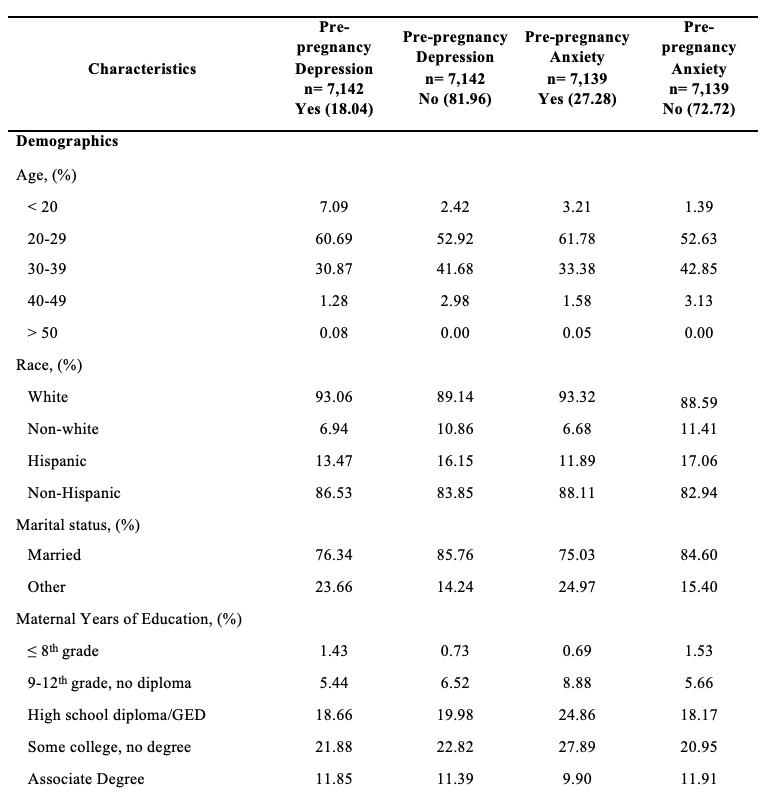

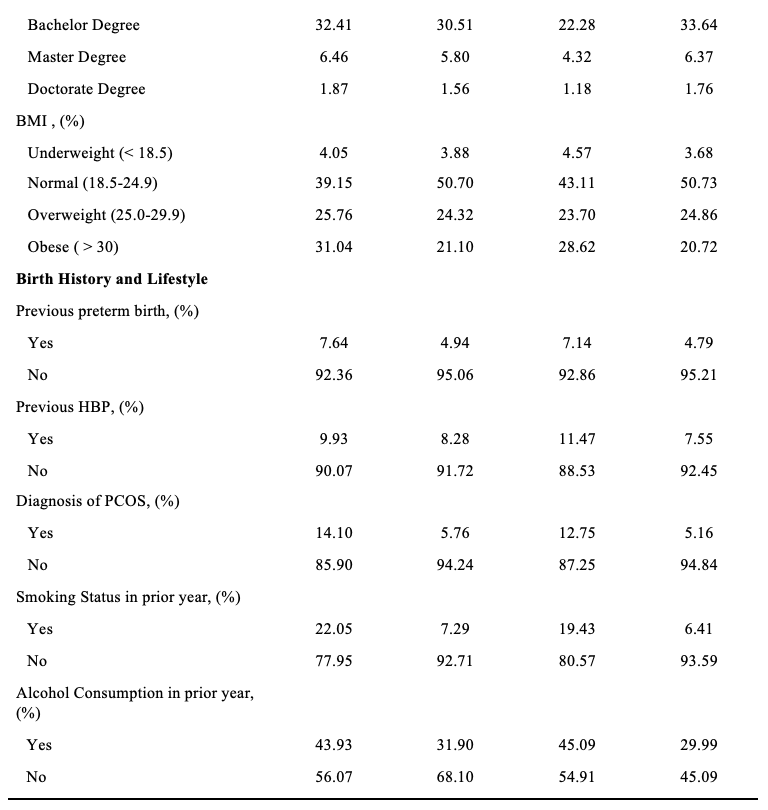

Of the women who participated in the 2016–2020 PRAMS questionnaire, 69.4% reported having no pre-pregnancy depression or anxiety, 14.5% had both pre-pregnancy depression and anxiety, 12.7% had anxiety, but no depression and 3.4% reported having depression but no anxiety (Figure 1). Women who experienced depression were more likely to be younger, white, have a previous preterm birth, smoke, drink, be obese, be less likely to be married, and have PCOS compared to those who do not experience depression (Table 1). There appeared to be no difference in the prevalence of previous high blood pressure (HBP) between women who reported depression and those who did not report depression. Women who reported having pre-pregnancy anxiety were more likely to be younger, white, have a previous preterm birth, smoke, drink, have PCOS, be obese, less likely to be married, and have previous HBP.

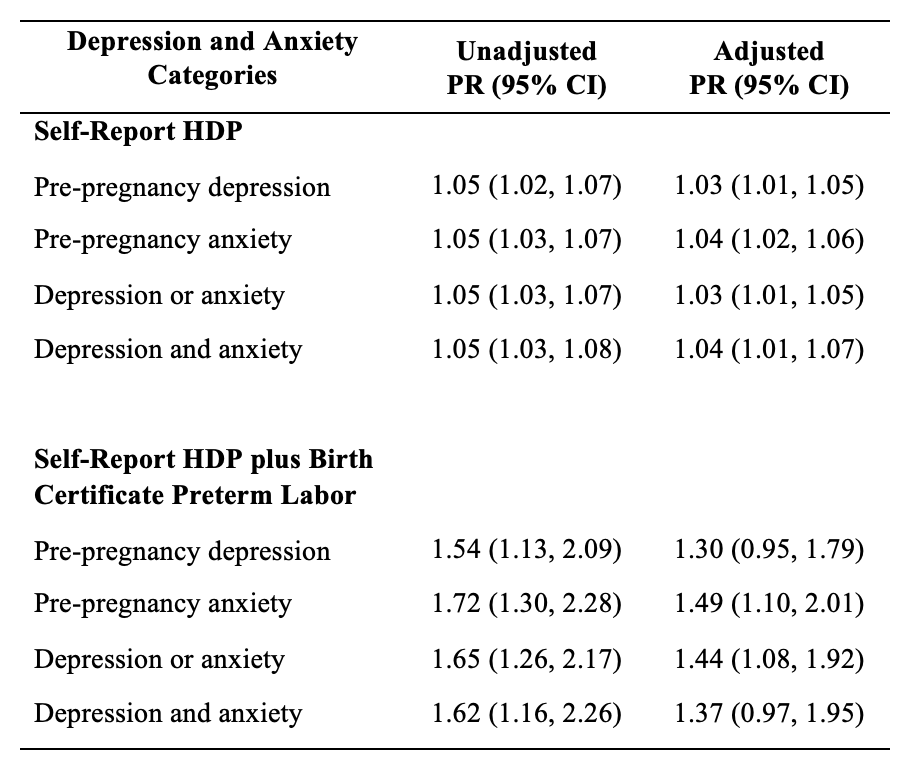

Women who reported pre-pregnancy depression and/or anxiety, compared to those who did not, had a 3–5% higher risk of having a hypertensive pregnancy after adjusting for maternal age, race, ethnicity, previous preterm birth, smoking status, prior alcohol consumption in the past two years, marital status, and pre-pregnancy BMI (Table 2). The prevalence increased to 30 to 49% when considering our defined “severe hypertensive pregnancy” that was accompanied by the preterm birth variable. Pre-pregnancy anxiety versus depression showed a greater association with having a severe hypertensive pregnancy, with an adjusted prevalence ratio of 1.49 (95% CI: 1.10, 2.01) for anxiety and 1.30 (95% CI: 0.95, 1.79) for depression. We found no evidence for effect modification by pregnancy year or Hispanic ethnicity (P=0.62 and 0.66 respectively).

Table 2: Unadjusted and adjusted prevalence ratios of HDP by self-reported hypertension during pregnancy and combined outcome of self-reported hypertension during pregnancy with preterm birth on birth record in Utah PRAMS (2016-2020), n=7,142 reflecting an estimated population of 231,242

Adjusted for maternal age, race, ethnicity, previous preterm birth, smoking status, prior alcohol consumption in the past two years, marital status, and BMI.

Discussion

In our study among Utah women participating in the PRAMs 2016–2020, we found that pre-pregnancy anxiety had a bigger effect on HDP than pre-pregnancy depression, with a nearly 50% increase in severe HDP among mothers who reported pre-pregnancy anxiety compared to those who did not have pre-pregnancy anxiety. These results slightly differed from observations made in the Michigan POUCH study, which found associations between both maternal chronic hypertension and pre-pregnancy depression/anxiety. While our study did not take into account the length of depression or anxiety symptoms or subcategorize HDP types (i.e., preeclampsia), the Michigan POUCH study made similar adjustments to maternal sociodemographic factors and found a larger association with pre-pregnancy anxiety than depression. Additional research is needed to differentiate risk between geographical areas.

Depression and HDP are thought to share a number of the same biological mechanisms.4 HDP is frequently linked to increased arterial stress and resistance in pregnant individuals.7 Research has demonstrated that individuals with depression also tend to exhibit increased arterial stiffness, which could potentially heighten their risk of developing HDP.4 Additionally, factors such as inflammation and oxidative stress have been shown to be associated with both depression and HDP, possibly creating a positive feedback loop between the two. 4 It is also important to note that some studies have shown that antidepressant and anxiolytic use in early pregnancy can contribute to HDP disorders and therefore must be considered when evaluating the association between depression and HDP.8

The strengths of this study include using a population-based sample that purposively includes at-risk mothers and a high response rate for sampling design. This study had several limitations as well. The cross-sectional study design limits our ability to infer causality between HDP and pre-depression and anxiety. In addition, while preterm birth does not necessarily mean the mother had HDP, the only cure for HDP is pregnancy or inducing the mother. It should be noted that we cannot be clear that the preterm birth was because of HDP.

There are multiple factors associated with HDP; this study supports that pre-pregnancy anxiety is a risk factor for HDP. The serious health problems caused by HDP affect both the mother and the baby across their lifespans. In order to reduce rates of HDP, the risk factors must be reduced. However, not all the associated factors are easy to address. Among the multiple factors associated with HDP, pre-pregnancy anxiety, and depression are factors that we can treat and intervene to reduce risk. This knowledge can lead to the development of programs and treatments focusing on pre-pregnancy anxiety and depression and could have implications for future treatments.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Data were provided by the Utah Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), a project of the Utah Department of Health (UDOH), the Office of Vital Records and Health Statistics of the UDOH, and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) of the United States Health and Human Services Department. This report does not represent the official views of the CDC, Utah Department of Health, or the NIH.

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank the contributions of Dr. Karen Schliep, Will Burnett, and Yunah Cho.

References

- Pearlstein T. Depression during Pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. Jul 2015;29(5):754-64. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.04.004

- Thombre MK, Talge NM, Holzman C. Association between pre-pregnancy depression/anxiety symptoms and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. J Womens Health (Larchmt). Mar 2015;24(3):228-36. doi:10.1089/jwh.2014.4902

- Ford ND, Cox S, Ko JY, et al. Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy and mortality at delivery hospitalization—United States, 2017–2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2022;71(17):585.

- Yuan M, Bedell S, de Vrijer B, Eastabrook G, Frisbee JC, Frisbee SJ. Highlighting the Mechanistic Relationship Between Perinatal Depression and Preeclampsia: A Scoping Review. Womens Health Rep (New Rochelle). 2022;3(1):850-866. doi:10.1089/whr.2022.0062

- Kalin NH. The Critical Relationship Between Anxiety and Depression. Am J Psychiatry. May 1 2020;177(5):365-367. doi:10.1176/app.ajp.2020.20030305

- Shulman HB, D’Angelo DV, Harrison L, Smith RA, Warner L. The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS): Overview of Design and Methodology. Am J Public Health. Oct 2018;108(10):1305-1313. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2018.304563

- Estensen, M.-E., Remme, E. W., Grindheim, G., Smiseth, O. A., Segers, P., Henriksen, T., & Aakhus, S. (2013, April). Increased arterial stiffness in pre-eclamptic pregnancy at term and early and late postpartum: A combined echnocardiographic and tonometric study. American Journal of Hypertension, 26(4), 549-556. DOI: 10.1093/ajh/hps067

- Bernard, N., Forest, J.-C., Tarabulsy, G. M., Bujold, E., Bouvier, D., & Giguere, Y. (2019). Use of antidepressants and anxiolytics in early pregnancy and the risk of preeclampsia and gestational hypertension: a prospective study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 19(146). DOI: 10.1186/s12884-019-2285-8

Citation

Lee J, Codd N, and Morgan H. (2024). Prenatal Depression and Anxiety and Risk of Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy: Findings from the Utah Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring Survey (2016–2020). Utah Women’s Health Review. doi: 10.26054/d-b4jk-797f