Table of Contents

Background

Obesity is a growing health problem that can adversely affect many aspects of health, including pregnancy. It is a common, serious, and costly disease that is more prevalent in disadvantaged and marginalized groups.1 Along with the many associated public health implications of obesity, some are specifically important in pregnancy and pediatric health, posing a challenge on obstetrics practice.

The standard measure of obesity is body mass index (BMI). A BMI greater than 30.0 kg/m² is considered obese, with BMI < 18.5 kg/m² considered underweight, 18.5 kg/m² ≤ BMI ≤ 24.9 kg/m² as normal weight, and 25 kg/m² ≤ BMI ≤ 29.9 kg/m² as overweight.2 While BMI can be reductive, it is the best tool for broad-based health policy perspectives.3

The seven domains of health influence obesity in pregnancy and its outcomes.4 When a woman is struggling in one domain, it can affect her ability to achieve a healthy state in others. Social health has effects on physical activity and diet that can come with cultural roots. Emotional health can be severely affected by obesity with weight gain and postpartum depression. Intellectual health may influence knowledge of the negative effects that are associated with pregnancy and obesity. Low socioeconomic status (SES) mothers have a higher risk of becoming obese due to inability to afford healthy foods. Struggling with obesity makes it much more difficult to return to a healthy state in each of the seven domains of health. These domains influence obesity, which leads to predisposing factors and early mortality for mothers and their babies.4

Researchers have found a correlation between obesity and miscarriage, stillbirth, diabetes, high blood pressure, cardiac dysfunction, renal dysfunction, hepatic dysfunction, sleep apnea, and risk of Cesarean section.5 Fetal risks in the setting of maternal obesity include birth defects, fetal macrosomia (larger than average size), impaired growth, asthma, and obesity.6 The purpose of this data snapshot is to characterize and describe the prevalence of obesity during pregnancy and its associated consequences in Utah and the United States.

Methods

Data was gathered from the Utah Maternal and Infant Health Program from 1993 to 2020. This program is an ongoing statewide monitoring system. After delivery of a live birth, the parent/parents are given a worksheet to fill out that will be used to create the child’s birth certificate; this worksheet also asks for information about the mother’s prepregnancy weight, height, and other social history and is added to the Utah Birth Certificate database.7 The BMI for each individual was calculated based on the data submitted to the Utah Office of Vital Records and Statistics. This data is then made available on the Public Health Indicator Based Information System (IBIS). Prevalence and 95% confidence intervals are reported. The national data used for comparison with the Utah data was obtained from the CDC website.

Results

Women who delivered a live birth during the years 1993 to 2020 and had a BMI that was classified as “obese” were used to calculate the following percentages. From Figure 1, it is evident that the prevalence of prepregnancy obesity has been increasing in Utah, reaching a high of 23.7% in 2020. However, this was still lower than the 2020 statistic for the entire United States of 30.0%.8

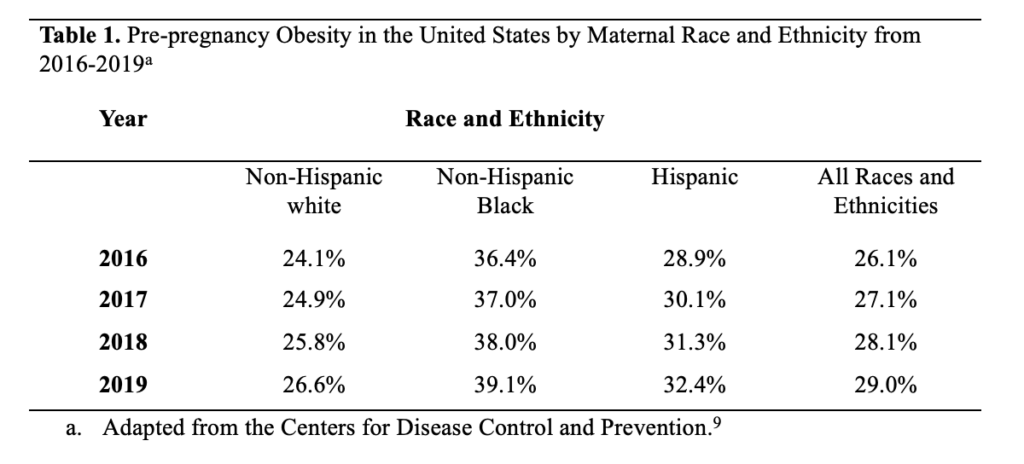

When comparing Figure 1 and Table 1, it is clear that prepregnant Utah women have a lower prevalence of obesity compared to women across the entire United States. However, both Utah and the United States show trends of consistent increase in prevalence of obesity.

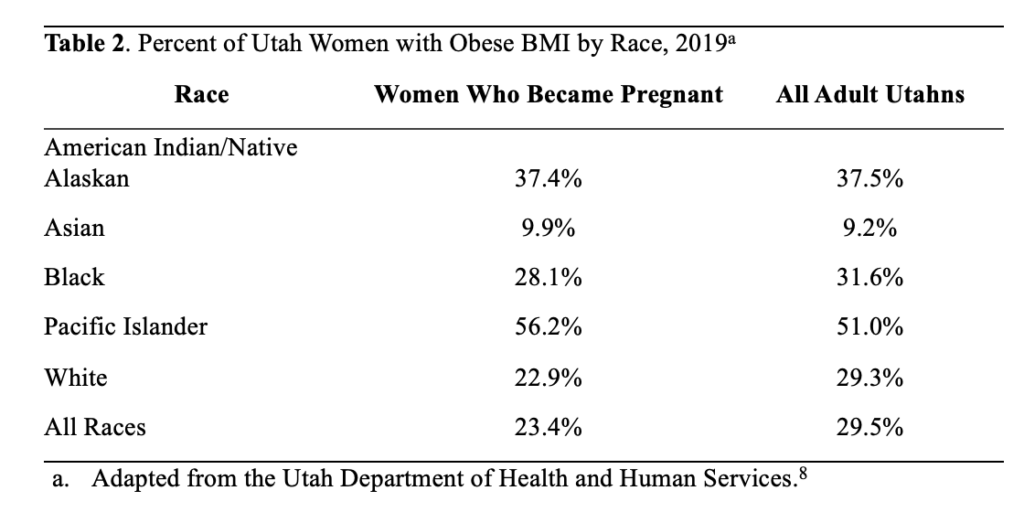

Table 2 compares the proportion of Utah women with a pre-pregnancy BMI of 30 or higher to the proportion of adult Utahns with a BMI in this range, stratified by racial group. Overall, only 23.4% of women who became pregnant were classified as obese, compared to 29.5% of Utahns as a whole. However, the proportion of Pacific Islanders with an obese pre-pregnancy BMI was higher than the overall proportion of Pacific Islander Utahns with an obese BMI (56.2% vs. 51.0%).

Discussion

Through the data gathered, it was found that of women who delivered live births, the proportion with a prepregnancy BMI of 30 kg/m2 or higher (those considered obese) has been steadily increasing. Since 1993, when the Utah Department of Health database first included this information, the percentage of obese pregnant women has increased from 9.6% to 23.7% in 2020. This number is lower than the United States average of 30% obese pregnant women in 2020, but still does not meet Healthy People 2030 objectives. By 2030, the Healthy People initiative aims to have 53.4% of U.S. women start pregnancy at a healthy weight; as of 2020, only 47.1% of Utah women met this standard.8 In addition, obesity rates in pregnant women are higher among those with lower education levels, lower income, and no health insurance, as well as those of Pacific Islander, Black, American Indian/Alaskan Native races, or Hispanic ethnicity.8

The increasing rates of obesity are concerning because of the many effects this can have on the health of the mother and the baby. A woman who is not at a healthy weight before becoming pregnant is more likely to have longer hospital stays and need more medical attention during pregnancy.8 Obese pregnant women are also at increased risk for many antepartum complications, including gestational diabetes, preeclampsia/eclampsia, stillbirth, and miscarriage.10 They are more likely to have longer labors, more fetal distress, and require a Cesarean section or operative vaginal delivery.8 This could possibly lead to more long-term health consequences as the newborn grows older and may affect subsequent pregnancies for the same woman. These complications can become very costly for the mother, especially considering that being below poverty level is a risk factor for obesity, and thus these women may be less able to afford treatment for these complications.

Much of what can be done in the public health sphere involves encouraging healthy weight and lifestyles before a woman even becomes pregnant. By doing so, public health can help prevent many of the complications that an obese woman may experience during pregnancy. Women should also receive regular well-woman care/visits from their primary caregivers. They can receive counseling, if needed, on weight, and on the risks that can come with an unhealthy weight once pregnant. Pregnant women should also receive proper education and counseling on healthy antepartum weight gain and postpartum weight loss.8 Additionally, the Utah Department of Health hosts a program called Healthy Environments and Active Living that provides education on physical activity and healthy eating habits, available to all Utah citizens.

While the data on obesity in pregnancy is helpful in beginning to address the problem, there are some limitations to this data. Data was obtained based on self-reporting by the mother shortly after the birth, and may be inaccurate due to recall error or misreporting. Because of this, both the Utah and nationwide estimates of prepregnancy obesity may be underestimated. Since data was only obtained for live births, it is unknown how obesity affects the number of stillborn and miscarried fetuses. It is also difficult to separate obesity from confounding risk factors such as poverty, race, low education, and lack of medical care. More in-depth studies would be needed to determine how much obesity plays a role in pregnancy complications, as opposed to some of the other mentioned risk factors. Finally, BMI has been used for many years as a standard for measuring health, but it is limited in what it can say about the health of an individual. It does not take into account diet, exercise, or other lifestyle choices. It would be valuable to consider additional health measures, not just BMI, when determining the health of a pregnant woman.

Despite these limitations, the data in this snapshot is beneficial and can be applied to other locations. The data was obtained from Utah’s birth certificate database. Birth certificates are documents produced nearly worldwide, and therefore this type of data collection can be repeated with many populations. Birth certificates only include live births, but they can be a good starting point to encourage more research in this area. The data may not be enough to draft policy, but it can help direct public health officials and policymakers towards the public health issues that need more attention. More education should also be targeted at pregnant and prepregnant women, especially those of American Indian/Alaska Native and Pacific Islander descent, as they have the highest rates of obesity. Additionally, more research should be conducted on obesity in all pregnancies (not just those ending in live births) and should examine obesity more closely in those areas of the population that are already at risk, such as those of lower socioeconomic status. Through additional research, a more complete picture can be attained of the risks of obesity in pregnancy and what can be done to best help those women most at risk.

Acknowledgements

Public Health Indicator Based Information System (IBIS) retrieved on March 10, 2022, from Utah Department of Health, Center for Health Data and Informatics, Indicator-Based System for Public Health. Website: http://ibis.health.utah.gov/

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adult Obesity Causes & Consequences. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published March 22, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/causes.htm

2. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Calculate Your BMI – Standard BMI Calculator. NIH.gov. Published 2019. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational/lose_wt/BMI/bmicalc.htm

3. CDC. About Adult BMI. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html

4. 7 Domains of Health – UWH Review. uwhr.utah.edu. Accessed March 17, 2022. https://uwhr.utah.edu/7-domains-of-health/

5. Fitch AK, Bays HE. Obesity definition, diagnosis, bias, standard operating procedures (SOPs), and telehealth: An Obesity Medicine Association (OMA) Clinical Practice Statement (CPS) 2022. Obesity Pillars. 2022;1:100004. doi:10.1016/j.obpill.2021.100004

6. Pregnancy and obesity: Know the risks. Mayo Clinic. Published 2018. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/pregnancy-week-by-week/in-depth/pregnancy-and-obesity/art-20044409

7. Birth Records | Utah Office of Vital Records and Statistics. vitalrecords.health.utah.gov. https://vitalrecords.health.utah.gov/records

8. IBIS-PH – Complete Health Indicator Report – Obesity in Pregnancy. ibis.health.utah.gov. Accessed March 10, 2022. https://ibis.health.utah.gov/ibisph-view/indicator/complete_profile/ObePre.html

9. A D. Increases in Prepregnancy Obesity: United States, 2016–2019. National Center for Health Statistics. Published November 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db392.htm

10. Leddy MA, Power ML, Schulkin J. The impact of maternal obesity on maternal and fetal health. Reviews in obstetrics & gynecology. 2008;1(4):170-178. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2621047/

Citation

Bellows E, Canning S, Price P, & Ricart H. (2023). Obesity in Pregnancy and its Effects: Utah 1993-2020. Utah Women’s Health Review. doi: 10.26054/0d-6pn3-80gy