Table of Contents

Abstract

Background: Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is prevalent in expecting mothers and is associated with various adverse maternal and fetal outcomes. Previous studies suggest a relationship between GDM and cesarean section (CS). However, the results of these studies in the context of primary CS and mothers’ age are limited and inconsistent, when other factors are accounted for.

Objective: This study compared primary CS risk between younger (15-34 years) and older (35+) mothers with GDM in Utah.

Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional analysis using the Utah Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) phase 8 (2016-2021) survey data. A total of 8,491 responses were available for analysis. We estimated the risk/prevalence ratio (PR) of primary CS in women with GDM using Poisson regression models.

Results: 18.44% of women with GDM also had a primary CS, compared to 10.95% with no GDM. Overall, GDM significantly increased primary CS risk (PR 1.39: 1.13, 1.72). Younger mothers (15-34) with GDM also had a stronger adjusted risk (PR 1.48: 1.15, 1.91), but not older mothers (PR 1.40: 0.95, 2.07).

Conclusion: This study found greater primary CS risk in younger mothers with GDM but not older mothers. Longitudinal studies and interventions focusing on modifiable risk factors in younger Utah mothers are warranted to enhance their health during pregnancy and childbirth. More research is also needed to better understand CS decisions among younger Utah mothers, in particular, those who develop comorbidities such as GDM.

Implications: Culturally and demographically tailored interventions are needed to reduce GDM and associated primary CS risk in this population.

Introduction

Gestational Diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a common complication during pregnancy, affecting more than 14% of pregnancies globally and 9% of pregnancies in the United States (US).1,2 In Utah, around 7.5% of pregnancies are affected by GDM.3 Some identified risk factors for GDM include advanced maternal age, obesity, and type 2 diabetes mellitus.4 Also, expecting mothers with GDM face an increased risk of preeclampsia, premature birth, cesarean section delivery (CS), and cardiovascular disease mortality.5,6

Among the various complications linked to GDM, a major concern is its strong association with CS. In the US, CS is among the most common major surgical procedures performed, accounting for 32.1% of births in 2022.7 In Utah, CS prevalence was 26.3% among low risk mothers with no prior births, in the same year.8 This is noteworthy as CS is also associated with adverse maternal outcomes such as endomyometritis, uterine rupture, and death.9,10

GDM is an independent predictor of CS in multiple previous studies.11–14 However, there are direct contradictions surrounding the context of maternal age in the association between GDM and CS, when other factors are accounted for.13,14 For example, one group found that the risk of CS was only increased in mothers aged 45 years or older.14 Other literature suggests a strong correlation of GDM and CS risk with increased age.13 Currently, there is no research investigating how maternal age may modify this association.

Generally, studies indicate age as a confounder, given that advanced maternal age has historically been linked to higher GDM and CS risks.13 However, recent reports suggest that younger mothers (under 35 years) may also face elevated risks of both conditions.7,15 Also, there are no studies assessing differences between younger and older mothers with GDM in the risk of a first or primary CS; most existing research has focused on total CS, history of CS, or repeat CS,11,13,16 requiring further investigation.

Moreover, to our knowledge, there has been no research examining age differences in primary CS risk within Utah mothers with GDM. To overcome these gaps, we utilized data from the Utah Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) phase 8 survey data, which included 8,491 mothers. We analyzed the data by stratifying mothers with GDM into two groups: younger (15-34 years) and older (35+), to assess their risk of a primary CS.

Methods

Study Design and Population

This study utilized the Utah Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) phase 8 (2016-2021) survey data for analysis. PRAMS is an ongoing population-based survey designed to collect information on maternal behaviors and experiences before, during, and immediately following pregnancy.17 Approximately 200 new mothers are randomly selected monthly for participation using Utah Birth Certificates. All responses are linked to the birth certificate record throughout the data collection process. Responses to the PRAMS survey are also weighted to accurately represent all women given birth in Utah.17 The dataset for the present study included 8,491 women, which reflected an extrapolated population size of 279,355 women in Utah (after weighing) using SAS analytical software package.

Exposure

The primary exposure was GDM, categorized as “Yes” or “No.” The information on GDM status was obtained from the PRAMS dataset which was linked to the infant’s birth certificate record.

Outcome

The outcome of interest was primary CS delivery categorized as “Yes” or “No.” The information on CS delivery was obtained from the PRAMS dataset which was linked to the infant’s birth certificate record.A “yes” for primary CS delivery indicates women with their first CS delivery reported in the birth certificate records, irrespective of the number of previous live births.

Covariates

Covariates used in the study included age (<20, 20-24, 25-34, and 35+ years of age), race (white or non-white), ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic), degree attained (associate’s degree or lower, bachelor’s degrees or higher, and unknown degree), region of residence (urban or rural), body mass index BMI (underweight: <18.5 kg/m2; healthy weight: 18.5-24.9 kg/m2; overweight: 25-29.9 kg/m2; and obese: >30 kg/m2),18 hypertension (yes or no), number of previous live births (0, 1-2, 3-4, and 5 or more), and infant birth weight (grams).

Statistical Analysis

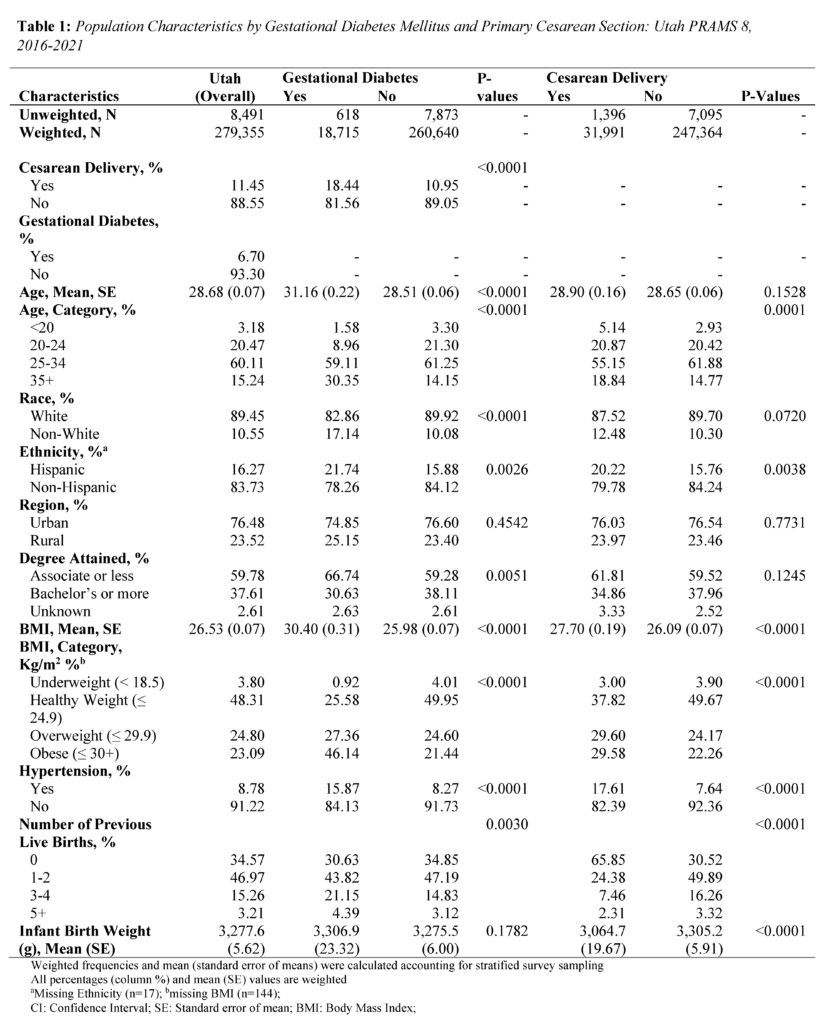

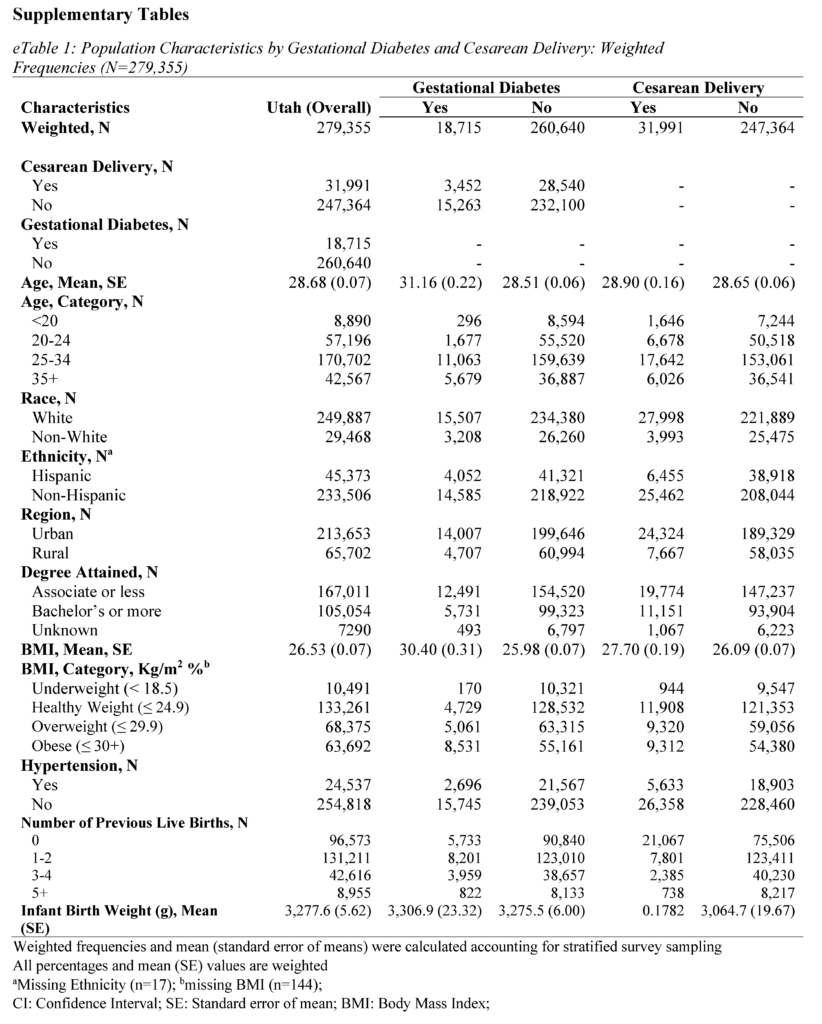

All analyses were conducted using SAS Studio (version 9.4). Sampling weights were applied to the analysis to obtain representative Utah population estimates. The PRAMS weighing methodology was provided by the CDC and Utah Department of Health and Human Services (UDHHS).19 Group differences for sample characteristics were calculated using chi-squared tests for categorical variables and student t-tests for continuous variables. The frequency distributions by GDM and primary CS are presented in Table 1 and eTables 1 and 2 (see Supplementary Materials).

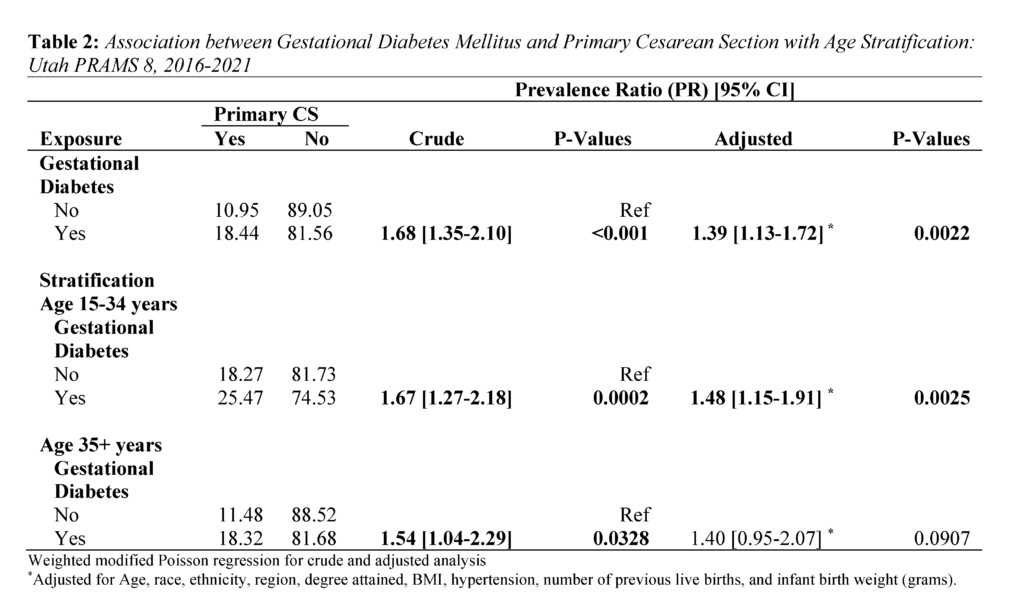

The modified Poisson regression was used to examine weighted crude and adjusted associations between GDM and CS.20 Prevalence Ratio (PR) estimates of the regression analysis are presented in Table 2. The Poisson regression was also used for age-stratified analysis of primary CS risk. Individual estimates for younger (15-34 years) and older mothers (35+) are also in Table 2. Age 35 and older was used as the cutoff point for stratification due to research suggesting 35 years as advanced maternal age.21

Ethics Approval

The collection of the data used in this study was approved by Utah Department of Health and Human Services (UDHHS) institutional review board.

Results

Population Characteristics

The study consisted of 8,491 respondents, reflecting 279,355 women giving birth in Utah after weighting. Mean (standard error) age was 28.68 (0.07) years, 89.45% identified as White race, and 83.73% identified as non-Hispanic ethnicity (Tables 1 and 2). In addition, 76.48% of women in the study lived in an urban setting, and 59.78% held an associate degree or lower.

About 6.70% of mothers in the study were diagnosed with GDM, and 11.45% of mothers had a primary CS. Mothers with GDM were more often older, evidenced by a mean age of 31.16 (standard error; SE = 0.22) years compared to 28.51 (SE = 0.06) years among mothers without GDM (P<.0001) (Table 1). Differences were observed between mothers with GDM and those without GDM in terms of race (P<.0001), ethnicity (P=0.0026), degree attainment (P=0.0051), BMI (P<.0001), comorbidity of hypertension (P<.0001), and number of previous live births (P=0.0030). (Table 1). Mothers with primary CS were more often Hispanic ethnicity (P=0.0038), had a higher BMI (P<.0001), comorbidity of hypertension (P<.0001), no previous live births (P<.0001), and lower infant birth weight (P<.0001).

Regarding the distribution of primary CS by GDM, 18.44% of mothers with GDM had primary CS, while 10.95% of mothers without GDM had a primary CS (P<.0001) (Table 1). Further, among younger mothers (15-34 years) with GDM, 25.47% had a primary CS. In contrast, among older mothers (35+) with GDM, 18.32% had a primary CS (Table 2).

Association between GDM and Primary CS delivery

Overall, GDM was strongly associated with primary CS (Table 2). Mothers with GDM had a 1.39 times higher adjusted risk of primary CS compared to those without GDM (PR 1.39: 1.13, 1.72). In the age stratified analysis, the adjusted risk of primary CS was 1.48 times significantly higher for mothers aged 15-34 (PR 1.48: 1.15, 1.91). In contrast, the adjusted risk for mothers aged 35+ years was (PR 1.40: 0.95, 2.07).

Discussion

Principal Findings

The present study provides a first look at primary CS risk in Utah mothers with GDM. It is unique in that it investigated differences between younger (15-34 years) and older (35+) mothers. We found that Utah mothers with GDM had a significantly higher risk of primary CS, and observed a stronger association in younger mothers (15-34 years).

Interpretation

Our first major finding regarding a higher risk of primary CS in mothers with GDM is consistent with other research.23 For example, the 2024 study by Fresch et al.23 found a 1.34 times higher adjusted risk of primary CS in mothers with GDM (PR 1.34: 1.31, 1.36). Medical conditions like suspected macrosomia, labor arrest, and indeterminate fetal heart rate tracing may make vaginal birth difficult and unsafe, requiring a CS.16,24 Importantly, GDM is a known independent risk factor which can exacerbate the occurrence of these conditions.24–26

In our second major finding, the risk of primary CS in mothers with GDM was higher across age groups but only significant for younger mothers ages 15-34. The estimates for this age group (PR 1.48: 1.15, 1.91) were higher than those of the overall population (PR 1.39: 1.13, 1.72). This result is surprising given that research generally indicates greater GDM and primary CS risk in advanced or older maternal age only.27 It is important to note that existing research has not specifically examined the associations in younger mothers. Instead, these studies have only used younger age as a comparison or reference group in their analyses.23,27 A recent US-based study, however, comparing primary CS prevalence between 2021 and 2022 showed increases for mothers ages 25-29 (21.0% vs 21.1%), 30-34 (33.8% vs 33.9%), 35-39 (26.1% vs 26.4%), and 40+ (33.7% vs 34.0%).7,28 The upward trend in younger mothers is noteworthy and highlights two key considerations. First, the risk of pregnancy complications in this age group may be higher than current estimates indicate. Second, younger expecting mothers may be underrepresented in maternity health research.

Several factors may be contributing to the rising CS rates among younger mothers. Common reasons include fear of labor pain (as a first time mother or following a previous birth), concerns about bodily changes and damage, concerns about their baby’s health, and convenience of scheduling a CS birth.29,30 In Utah, a 2013 PRAMS data report revealed labor challenges indicated by fetal monitor, prolonged labor, and failed labor induction as reasons for CS in mothers reporting a primary CS.31 Given that GDM is associated with many, if not all, of these complications, it is possible that a diagnosis of the condition may heighten fear of a vaginal delivery, particularly among younger expecting mothers, which may result in preference for a CS. We recommend further research be performed to confirm this relationship.

Health Implications

CS intersects with various domains of health. In terms of physical health, CS has associated complications for both the mother and child. CS is a risk factor for common gynecological conditions, including the development of urinary tract infections, gastrointestinal problems, adhesions, pain, infertility, painful menses, and endometriosis in the mother.9,32 Additionally, children born via CS are at increased risk for respiratory tract infections, asthma, and obesity.33

The economic health domain is also impacted. On average, CS is more costly for the patient and for the hospital than vaginal delivery. Across Utah, total CS costs are reported as $8,952.52 for those with insurance and $14,252.80 for those without insurance while vaginal births are reported as $5,951.76 and $10,199.52 with and without insurance, respectively.34 Much of this cost is taken care of by insurance companies. However, these costs do not consider any complications stemming from delivery or care for mother or child. For the social health domain, CS can impact family planning and relationships due to potential complications such as painful intercourse and infertility.9,32,35 In mental and behavioral health, the increased risk of complications and the recovery process resulting from CS can lead to stress, anxiety, and even delayed initiation of breastfeeding.36,37

In 2023, Utah’s CS rate (19.4%) was lower than the average rate across the United States (US, 26.3%) for low-risk women without prior births.8 This trend has remained consistent over time (2013-2023).8 Additionally, Utah has a lower rate of GDM (7.5%) compared to the US (9%), although this difference is small.3 One explanation for this difference is the younger age of mothers at their first birth in Utah compared to the US (25.9 in Utah versus 27.1 years overall in 2020).38

It is critical that the aforementioned issues are addressed to improve maternal and child health outcomes. We recommend the following actions for health systems and population health researchers in Utah. First, the necessity of CS should be carefully considered in the context of each expecting mother. It is equally important that cases of CS in young expecting mothers with GDM are closely reviewed to ensure that decisions for CS follow appropriate clinical guidelines. Second, health systems should provide interdisciplinary team-based care to support young mothers who develop comorbidities (such as GDM) to mitigate fear and worry about their pregnancy. Third, significant outreach is needed to increase awareness about comorbidities during pregnancy and how expecting mothers can protect their health and the health of their baby. Lastly, more work is needed in Utah to ensure that new and expecting younger mothers are represented in maternity health research.

Conclusions

In summary, this study contributes valuable insights into the association between GDM and primary CS in Utah, highlighting the importance of early detection and management of GDM to optimize maternal and infant health outcomes. Longitudinal studies and interventions focusing on modifiable risk factors in younger Utah mothers are warranted to enhance their health during pregnancy and childbirth. More research is also needed to better understand CS decisions among younger Utah mothers, in particular, those who develop comorbidities such as GDM.

Strengths & Limitations

This study had several strengths and limitations. First, our weighted sample was representative of the Utah population (279,355). This enabled more precise estimates and comprehensive evaluation of overall findings. Second, this study was unique as it is the first to examine GDM and the risk of CS within the Utah population. Concerning limitations, since the study utilized Utah population data, the findings may not be generalizable to other areas. Further, the study design was cross-sectional, which introduces temporal ambiguity. As this analysis was done at one point, it cannot establish a cause-and-effect relationship.

Acknowledgements

Data was provided by the Utah Pregnancy Risk Assessment and Monitoring System (PRAMS), a project of the UDHHS, Office of Maternal and Child Health (MCH). No funding was provided for the project. This information or content and conclusions are those of the author and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by UDHHS MCH.

References

1. Wang H, Li N, Chivese T, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Estimation of Global and Regional Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Prevalence for 2021 by International Association of Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group’s Criteria. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183:109050. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109050

2. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. About Gestational Diabetes. Diabetes. Published May 31, 2024. Accessed July 25, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/about/gestational-diabetes.html

3. Utah Department of Health and Human Services. IBIS-PH – Health Indicator Report – Diabetes: gestational diabetes. Accessed July 24, 2024. https://ibis.utah.gov/ibisph-view/indicator/view/DiabGestDiab.html

4. Casagrande SS, Linder B, Cowie CC. Prevalence of gestational diabetes and subsequent Type 2 diabetes among U.S. women. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;141:200-208. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2018.05.010

5. Preda A, Pădureanu V, Moța M, et al. Analysis of Maternal and Neonatal Complications in a Group of Patients with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57(11):1170. doi:10.3390/medicina57111170

6. Wang YX, Mitsunami M, Manson JE, et al. Association of Gestational Diabetes With Subsequent Long-Term Risk of Mortality. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2023;183(11):1204-1213. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.4401

7. Osterman M, Hamilton B, Martin J, Driscoll A. National Vital Statistics Reports Volume 73, Number 2, April 4, 2024. Published online April 4, 2024.

8. Utah Department of Health and Human Services. IBIS-PH – Health Indicator Report – Cesarean delivery among low risk women with no prior births. Accessed July 24, 2024. https://ibis.utah.gov/ibisph-view/indicator/view/CesDel.UT_US.html

9. Quinlan JD, Murphy NJ. Cesarean Delivery: Counseling Issues and Complication Management. afp. 2015;91(3):178-184.

10. Boyle A, Reddy UM, Landy HJ, Huang CC, Driggers RW, Laughon SK. Primary Cesarean Delivery in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(1):33-40. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182952242

11. Gorgal R, Gonçalves E, Barros M, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus: A risk factor for non-elective cesarean section. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 2012;38(1):154-159. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0756.2011.01659.x

12. Song J, Cai R. Interaction between smoking during pregnancy and gestational diabetes mellitus and the risk of cesarean delivery: evidence from the National Vital Statistics System 2019. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2023;36(2):2259048. doi:10.1080/14767058.2023.2259048

13. Akinyemi OA, Weldeslase TA, Odusanya E, et al. Profiles and Outcomes of Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in the United States. Cureus. 2023;15(7):e41360. doi:10.7759/cureus.41360

14. Claramonte Nieto M, Meler Barrabes E, Garcia Martínez S, Gutiérrez Prat M, Serra Zantop B. Impact of aging on obstetric outcomes: defining advanced maternal age in Barcelona. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2019;19(1):342. doi:10.1186/s12884-019-2415-3

15. Shah NS, Wang MC, Freaney PM, et al. Trends in Gestational Diabetes at First Live Birth by Race and Ethnicity in the US, 2011-2019. JAMA. 2021;326(7):660-669. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.7217

16. Caughey AB, Cahill AG, Guise JM, Rouse DJ. Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2014;210(3):179-193. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.01.026

17. Utah Department of Health and Human Services. Utah PRAMS | Maternal and Infant Health Program. Accessed July 25, 2024. https://mihp.utah.gov/pregnancy-and-risk-assessment

18. CDC. Defining Adult Overweight and Obesity. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published June 3, 2022. Accessed September 28, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/basics/adult-defining.html

19. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Data Methodology. Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS). Published May 20, 2024. Accessed July 25, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/prams/php/methodology/index.html

20. Lindquist K. How can I estimate relative risk in SAS using proc genmod for common outcomes in cohort studies? | SAS FAQ. Accessed January 17, 2024. https://stats.oarc.ucla.edu/sas/faq/how-can-i-estimate-relative-risk-in-sas-using-proc-genmod-for-common-outcomes-in-cohort-studies/

21. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Pregnancy at Age 35 Years or Older: ACOG Obstetric Care Consensus No. 11. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2022;140(2):348. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004873

22. Marshall SW. Power for tests of interaction: effect of raising the Type I error rate. Epidemiol Perspect Innov. 2007;4:4. doi:10.1186/1742-5573-4-4

23. Fresch R, Stephens K, DeFranco E. The Combined Influence of Maternal Medical Conditions on the Risk of Primary Cesarean Delivery. AJP Rep. 2024;14(1):e51-e56. doi:10.1055/s-0043-1777996

24. Kc K, Shakya S, Zhang H. Gestational diabetes mellitus and macrosomia: a literature review. Ann Nutr Metab. 2015;66 Suppl 2:14-20. doi:10.1159/000371628

25. Gill P, Henning JM, Carlson K, Van Hook JW. Abnormal Labor. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Accessed July 26, 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459260/

26. Depla AL, De Wit L, Steenhuis TJ, et al. Effect of maternal diabetes on fetal heart function on echocardiography: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2021;57(4):539-550. doi:10.1002/uog.22163

27. Richards MK, Flanagan MR, Littman AJ, Burke AK, Callegari LS. Primary cesarean section and adverse delivery outcomes among women of very advanced maternal age. J Perinatol. 2016;36(4):272-277. doi:10.1038/jp.2015.204

28. Osterman MJK, Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Driscoll AK, Valenzuela CP. Births: Final Data for 2021. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2023;72(1):1-53.

29. Stoll KH, Hauck YL, Downe S, Payne D, Hall WA. Preference for cesarean section in young nulligravid women in eight OECD countries and implications for reproductive health education. Reprod Health. 2017;14:116. doi:10.1186/s12978-017-0354-x

30. Stoll K, Edmonds JK, Hall WA. Fear of Childbirth and Preference for Cesarean Delivery Among Young American Women Before Childbirth: A Survey Study. Birth. 2015;42(3):270-276. doi:10.1111/birt.12178

31. Utah Department of Health and Human Services. Utah Health Status Update: Primary Cesarean Delivery. Published June 2013. Accessed July 26, 2024. https://ibis.utah.gov/ibisph-view/pdf/opha/publication/hsu/2013/1306_CSection.pdf

32. Antoine C, Young BK. Cesarean section one hundred years 1920-2020: the Good, the Bad and the Ugly. J Perinat Med. 2020;49(1):5-16. doi:10.1515/jpm-2020-0305

33. Słabuszewska-Jóźwiak A, Szymański JK, Ciebiera M, Sarecka-Hujar B, Jakiel G. Pediatrics Consequences of Caesarean Section-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):8031. doi:10.3390/ijerph17218031

34. Peter K. Costs of Childbirth by State. PolicyScout. August 17, 2022. Accessed August 15, 2024. https://policyscout.com/health-insurance/learn/costs-childbirth-by-state#

35. Kainu JP, Sarvela J, Tiippana E, Halmesmäki E, Korttila KT. Persistent pain after caesarean section and vaginal birth: a cohort study. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2010;19(1):4-9. doi:10.1016/j.ijoa.2009.03.013

36. Skov SK, Hjorth S, Kirkegaard H, Olsen J, Nohr EA. Mode of delivery and short-term maternal mental health: A follow-up study in the Danish National Birth Cohort. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2022;159(2):457-465. doi:10.1002/ijgo.14155

37. Hosaini S, Yazdkhasti M, Moafi Ghafari F, Mohamadi F, Kamran Rad SHR, Mahmoodi Z. The relationships of spiritual health, pregnancy worries and stress and perceived social support with childbirth fear and experience: A path analysis. PLoS One. 2023;18(12):e0294910. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0294910

38. Pieper K, Seager M, Blackburn R. Utah Women and Fertility: Trends and Changes from 1970–2021. Published online April 4, 2023.

Supplementary Materials

Citation

Adediran E, Duffy HR, & Asay KM. (2024). Does Maternal Age Modify the Association Between Gestational Diabetes and Primary C-section Delivery? A Cross-Sectional Study of Utah PRAMS Data. Utah Women’s Health Review. doi: 10.26054/d-yx18-mp3d