Table of Contents

Abstract

Preterm birth is the major cause of neonatal mortality and morbidity. Recent studies have suggested that there may be an association between periodontal disease and delivery of preterm and or low birth weight infants. This paper summarizes the results of a pilot study conducted to evaluate the relationship between periodontal disease and preterm low birth weight. This study also explores whether providing clinical preventive periodontal intervention can reduce the risk of adverse birth outcomes. The findings of this evaluation study indicate that there are potential avenues which can be explored to develop a cost analysis for periodontal treatment to be included as a covered benefit for pregnant women.

Introduction

Preterm birth (PTB) is a major public health problem. The rate of preterm birth has increased significantly in the last decade. In 2004, 12.5% of the births in the U.S. were preterm (i.e., occurred before 37 weeks of gestation) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006). Preterm birth and associated low birth weight (PLBW) represent the major causes of neonatal mortality and morbidity, including neurodevelopmental disabilities, congenital anomalies and behavioral disorders (Vohr et al., 2000). It is estimated that, each year, more than five billion dollars are spent in the U.S. for neonatal care, with the majority of this amount consumed in caring for PLBW infants (Khader, 2005).

Although about half of PTBs have no known risk factors linked with them (Iams et al., 2001), there is emerging evidence of the association between periodontal infection and the risk of PLBW. Studies in this area, using a variety of research designs, have resulted in varied findings. Offenbacher et al. (1996) found a statistically significant association between periodontal disease in pregnant women and PLBW infants. The authors determined that mothers with periodontal infection had more than seven times the risk of delivering a PLBW infant, even after adjusting for other potential risk factors. Jeffcoat et al. (2001) also found an association between periodontal infection and PTB. A randomized controlled trial concluded that periodontal disease appeared to be an independent risk factor for PLBW and that periodontal therapy significantly reduced the rates of PLBW in the women with periodontal disease (Lopez et al., 2002). On the other hand, several epidemiologic studies have concluded that there was no association between periodontal disease and birth outcomes (Davenport et al., 2002; Moore et al., 2004).

Previous studies have not assessed the association between periodontal disease and PLBW among the Medicaid population. Hence, this Utah pilot study, using a sample of pregnant women enrolled in Medicaid, was undertaken to: 1) understand the extent of periodontal disease among pregnant women; 2) assess the association between periodontal disease and PLBW; and 3) determine the possible benefits of preventive intervention in reducing the risk of PLBW. This project represented an effort to evaluate the current standard of care provided by Medicaid, and was a collaborative endeavor between Health Care Financing (Medicaid) and the Maternal and Child Health Bureau both part of the Utah Department of Health (UDOH).

Materials and Methods

Study Population

The study population consisted of pregnant women enrolled in Medicaid. Medicaid eligibility for pregnant women in Utah is at 133% of the Federal Poverty Level. Originally this study planned to include three Medicaid Family Dental Plan (FDP) clinics: South Main Clinic in Salt Lake City, Ellis Shipp Clinic in West Salt Lake City, and Provo Clinic. However, during the implementation stage, the study was limited to the South Main dental clinic located in Salt Lake County (the most populous county in Utah). The Institutional Review Board at UDOH reviewed and exempted the study from requiring approval on the basis that the study would serve as a program evaluation “pilot” project. The research group from Medicaid requested that the Department of Workforce Services refer Medicaid eligible pregnant women to this clinic. When women came for their dental visits, they were asked if they would be willing to participate in this pilot study. After the verbal consent was received, the FDP clinic staff administered an intake questionnaire, which included pregnancy history, medical conditions, and demographic information. The completed intake questionnaire containing the subject’s signature served as the final consent for participation in the study. Based on this convenience sample, a total of 460 pregnant women were recruited for this study.

Measurement of clinical periodontal status

The periodontal examination was performed using a tool called a PSRTM (Periodontal Screening & Recording, American Dental Association, 1992). The PSR is a specifically designed periodontal probe that features a 0.5mm balled end and a colored band extending from 3.5 to 5.5mm from the tip. A PSR score is determined by assessing how much of the colored band on the PSR probe is visible when the PSR probe is placed in the gingival crevice. The scoring system ranges between 0 – 4. A detailed description of PSR coding is provided in Chart 1. All study participants received a full mouth periodontal assessment. The mouth was divided into sextants–maxillary right, anterior, and left; mandibular left, anterior, and right–and a numeric score was assigned to each area. A dentist, who had been calibrated prior to the study, conducted all clinical periodontal examinations at the project site.

The criteria used to determine the presence of periodontal disease were based on PSR scores. Study participants with PSR scores under 3 in all sextants were defined as exhibiting no periodontal disease. Women with a score of 3 or greater in one or more sextant(s) were diagnosed as having periodontal disease.

Study intervention

After the periodontal assessment, the study participants were screened for intervention eligibility. Only pregnant women between 22 and 26 weeks gestation with periodontal disease were eligible to receive preventive clinical intervention or periodontal treatment. The intervention in this study consisted of dental prophylaxis, including rubber cap polish and periodontal deep scaling. Those women with periodontal disease who received periodontal treatment were defined as the “intervention” group. The intervention group also received instruction in oral hygiene. Those women who were diagnosed with periodontal disease, but who did not return to the clinic to receive the periodontal treatment or did not receive treatment within the 22-26 week window, were defined as the “non-intervention” group. During the planning stage of the study, an anticipated 30% no-show rate for the dental prophylaxis treatment was anticipated. Group designation was recorded in each subject’s treatment chart. The same examiner performed all examinations and measurements.

Data Collection

The recruitment of study participants was done over a three-year period (October 2003 to September 2006) at the South Main project site. Socio-demographic information, pregnancy and medical history were collected at baseline by a structured intake questionnaire. This collection of information was followed by a clinical full-mouth periodontal examination where a PSR score was recorded. The FDP clinic staff reminded participants of their scheduled periodontal intervention appointments. PSR scores and the types of interventions given were recorded on the subject’s treatment form.

Information on labor/delivery, birth outcome and health of the newborn were collected from birth certificate data. All intake questionnaires and treatment forms were provided to UDOH by the project site dental clinician for data entry and linkage with birth certificate data.

Study Outcomes

Gestational age and birth weight were selected as the main birth outcome characteristics of interest. Additionally, birth outcome characteristics were further subdivided into several categories: preterm (<37 weeks gestation), extreme preterm (<32 weeks gestation), low birth weight (LBW, <2,500 g), very low birth weight (VLBW, <1,500 g), and PLBW (<37 weeks gestation and <2,500g). Birth outcomes were determined by linking dental clinic data (intake and treatment forms) with birth certificate data. The calculation of gestational age at delivery was based on the clinical estimate of gestation recorded on the birth certificate. This clinical estimate on the birth record is defined as the age in total weeks completed from the last menstrual period date to the date of delivery.

Statistical Analyses

The dental clinic data were merged with birth certificate 2003-2006 data. Since the birth certificate 2006 data were not finalized at the time of analysis, preliminary 2006 birth data (available through Medicaid Data Warehouse) were used for this pilot study. Linkage was performed in multiple cycles using both deterministic and probabilistic approaches. Analyses for this study included descriptive statistics, chi squared tests, t-tests and logistic regression. All analysis was performed using SAS version 9.1.

Results

A total of 460 pregnant women were recruited from the FDP clinic to participate in this pilot study. These dental clinic data were merged with birth certificate data. Deterministic linkage generated 403 matched records from the possible 460 dental clinic records. Use of mother’s name, date of birth (DOB), and infant delivery date generated an additional 14 matched records, yielding a total of 417 cases. Forty-three cases were unmatched due to incomplete information (missing DOB and names), miscarriages, or fetal deaths. Women with multiple gestations were excluded from the analysis. A total of 400 women with singleton births were included in the final study sample. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the study participants. The majority (71.7%) of the study participants were 20-29 years old. About ninety-two percent of the participants were white. Thirteen percent of the study population was of Hispanic/Latina ethnicity. Close to one in five (18.1%) women smoked during pregnancy. More than three-fourths (77.8%) of women began prenatal care during their first trimester. Approximately five percent of women had a history of previous preterm birth.

A summary of the periodontal disease status of study participants based on PSR scores is presented in Table 2. PSR scores of 0-2 indicate a gingival pocket depth of less than 3.5 mm, and were considered as absence of periodontal disease. Scores of 3-4 indicate a pocket depth of at least 3.5 mm or greater, and were considered as indication of the presence of periodontal disease. More than a third (40.5%) of the participants was diagnosed with periodontal disease.

Women participating in the study diagnosed with periodontal disease were eligible to receive a clinical preventive intervention between 22-26 weeks’ gestation. Of the 162 women with periodontal disease, 108 women received the intervention. The remaining 54 women with periodontal disease who did not receive intervention became the comparison group against which to evaluate the birth outcomes and benefits of the interventions. Table 3 provides the demographic characteristics, and the pregnancy and medical history characteristics of both intervention and non-intervention groups. The average ages of intervention and non-intervention groups were similar. However, there was a significant difference in educational levels between the groups. The intervention group had a higher proportion of women with education beyond high school compared to the non-intervention group (33% vs. 21%, p=.05). The non-intervention group contained a higher percentage of nulliparous women and smokers than the intervention group, although these differences were not statistically significant. Eight women in the intervention group had a history of preterm birth compared to only one in the non-intervention group. The data illustrate that a higher proportion of women in the non-intervention group had urinary tract infections and bacterial vaginosis compared to women in the intervention group, but the differences were not statistically significant. In both groups, all women with infections had treatment, as reported on the intake form.

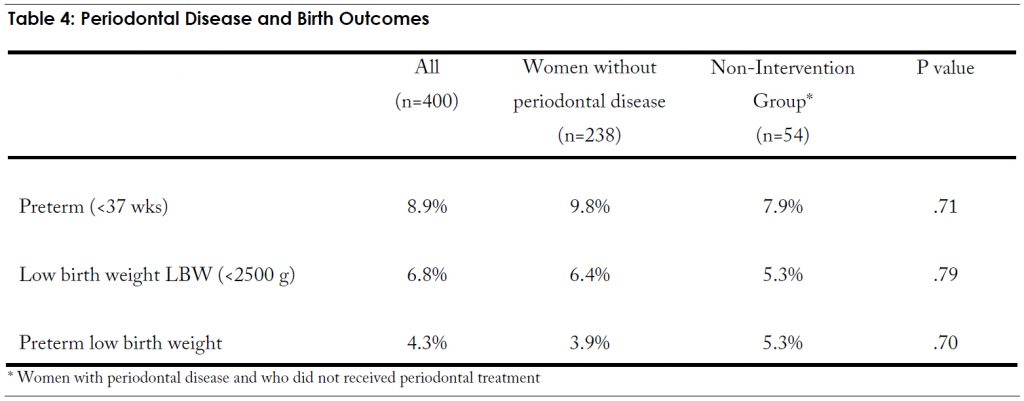

In order to assess the relationship between periodontal disease and adverse birth outcomes, analysis included women with no periodontal disease (PSR code <2) and those with periodontal disease who received no intervention. We excluded the women with periodontal disease and who received periodontal treatment from this particular analysis. The comparisons of birth outcomes are presented in Table 4. The rates of PLBW were slightly higher among women with periodontal disease (non-intervention group) compared to women without periodontal disease (5.3% vs. 3.9%), however, these differences were not statistically significant even controlling for the effects of smoking. The data shows that there were no significant associations between periodontal disease and adverse birth outcomes (preterm, low birth weight, or preterm low birth weight).

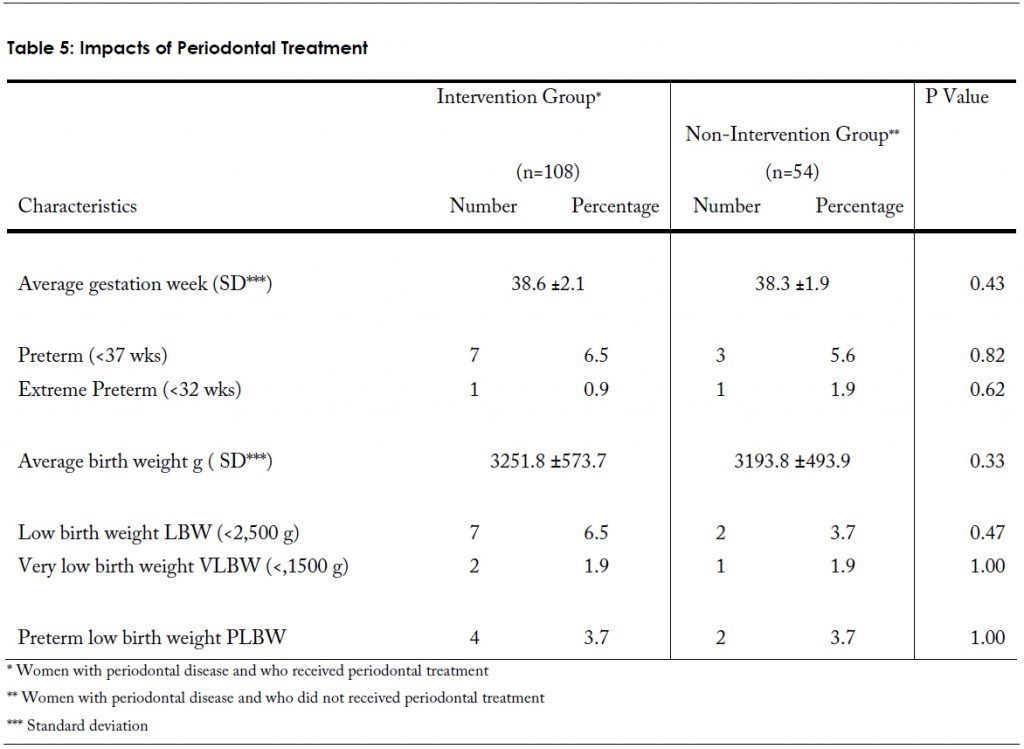

The impacts of periodontal treatment and associated birth outcomes are shown in Table 5. Infants in the intervention group had a higher average gestational age (38.6 ±2.1 vs. 38.3 ±1.9) and a higher average birth weight (3251.8 ±573.7 vs. 3193.8 ±493.9) than in the non-intervention group, but the differences were not significant. Neither preterm nor extreme preterm categories were significantly different when both groups were examined. This pattern was also observed for LBW and VLBW categories. It is possible that the lack of significant differences in birth outcomes, between the intervention group and the non-intervention group, may be attributed to small numbers rather than the effect of periodontal treatment. Interpretations of results are difficult due to these small numbers.\

Discussion

Preterm birth in Utah is of great concern to public health professionals, because preterm infants are at significant risk for serious and lasting health problems. In 2005, of the 51,517 live births in Utah, 10% were preterm. Among the total Medicaid population the preterm rate was higher, at 11%. The state singleton preterm birth rate was 8%, while the Medicaid rate was close to 10%.

The average costs associated with one preterm infant range from $8,000 to more than $70,000 (UDOH, 2005). Based on 2005 hospital discharge data, $165 million were spent statewide on the care of preterm infants. The Medicaid population accounted for 39% of premature births (n=1,981) and consumed more than $63 million (UDOH, 2005). The costs of caring for these numbers of preterm infants are staggering, both in terms of immediate health care dollars and long-term impacts on families and society.

While the economic expense associated with PLBW infants is huge, the cost of providing thorough periodontal intervention is modest. The cost of periodontal treatment that includes dental prophylaxis, scaling, and root planing averages from approximately $32 to $1,000 per patient. Even if providing such periodontal intervention to pregnant women had only modest impacts on the incidence of preterm birth, the economic savings would be immense.

The UDOH conducted this pilot project as a program management/program evaluation study for the purpose of optimizing service delivery. One of the purposes of this study was to understand the extent of periodontal disease among the Medicaid population of pregnant women in Utah. It was found that more than one third (41%) of women referred for dental care to the study site were diagnosed as having periodontal disease. This study also found no statistically significant association between periodontal disease and risk of PLBW. The data indicated that the periodontal intervention did not significantly alter rates of PLBW.

There are important limitations to keep in mind as the results of this pilot study are compared to those of other studies. The study population was based on a convenience sample without any randomization applied. It consisted only of pregnant women who appeared at the Salt Lake County South Main FDP clinic for dental care and who were willing to participate in this study. Initially this study was planned to include multiple dental clinicians in three FDP clinics. However, this pilot study was only implemented in one site. The participation of only one clinic site greatly prolonged the time required to gather adequate data for analysis. This situation placed an extra burden on one site and limited the possibility of generalizing the findings of the study to the entire Medicaid pregnant population in Utah. The small numbers of women in the intervention and non-intervention groups, made it unfeasible to control for potentially confounding factors. Larger numbers of cases are necessary to provide more reliable estimates of statistical significance.

The results of the pilot study may not be comparable with those of other studies due differences in clinical preventive interventions. Other studies have often included plaque control, scaling, and root planing as preventive interventions (Lopez et al., 2002; Offenbacher et al., 1996). In this UDOH study, rubber cap polish and periodontal deep scaling were offered as interventions. Root planing was not offered. The criteria for the diagnosis of periodontal disease also vary from study to study.

The optimal time for providing dental care to pregnant women for maximum effectiveness in impacting preterm birth is unknown. It is possible that periodontal intervention was delivered too late in pregnancy for maximum impact on birth outcome. Studies have varied in terms of the timing of interventions. Some offered the interventions before 20 weeks’ gestation, while others offered interventions before 35 weeks’. The window of intervention for this study was set between 22-26 weeks. The recommendation made by Michalowicz et al. (2006, p.1893) appears wise, that additional studies are needed to determine “whether the provision of periodontal treatment even earlier in pregnancy or before conception might improve birth outcomes.”

A portion of our study population received antibiotics during pregnancy as treatment for infections. Such antibiotic treatment can confound the effects of periodontal interventions (Jeffcoat et al., 2001; Michalowicz et al., 2006). We were unable to control for type of treatment due to lack of data.

Recommendations

Although the present study disclosed no association between periodontal disease and adverse birth outcomes, other research has established possible connections between oral bacteria and systemic diseases, including PLBW. Hence, it is advisable for public health professionals, clinical practitioners, and health care policy makers to make optimal dental care available to all pregnant women. As a means of prevention, it is prudent for pregnant women to be screened for periodontal disease and referred to periodontal specialists in order to avoid the potential for unfavorable birth outcomes. All pregnant women, and women considering pregnancy, should have dental check-ups, including a gingival evaluation. Dental visits during pregnancy provide an ample opportunity to educate women about the importance of oral health both to their own overall health, and to the overall health of their children. Since the emotional and financial costs of prematurity are immense, caution would recommend easy access to periodontal care for all pregnant women. Such a recommendation is consistent with the health guidelines for pregnant women suggested by the Baby Your Baby and Mind Your Mouth programs at the UDOH. The findings of this evaluation study indicate that there are potential avenues which can be explored to develop a cost analysis for periodontal treatment to be considered for inclusion in a benefits package for pregnant women. Preventive interventions have been shown to be more cost effective than treatment.

In the future, further study using a scientifically oriented research design would be prudent. It would provide an opportunity to address the uncertainties raised by the limitations of this pilot study.

References

- American Dental Association and The American Academy of Periodontology. (1992). Periodontal screening & recording. Retrieved December 19, 2005, from http://www.ada.org/prof/resources/topics/perioscreen/index.asp.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2006). Births: Final data for 2004. National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 55, No. 1. 1-102.

- Davenport, E.S.; Williams, C.; Sterne, J.; Murad, S.; Sivapathasundram, V.; Curtis, M.D. (2002). Maternal periodontal disease and preterm low birthweight: Case-control study. J Dent Res, Vol. 81(5), 313-318.

- Iams, J.D.; Goldenberg, R.L.; Mercer, B.M. (2001). The preterm prediction study: Can low-risk women destined for spontaneous preterm birth be identified? American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Vol. 184, 652-655.

- Utah Department of Health, Center for Health Data, Indicator-Based Information System for Public Health website: http://ibis.health.utah.gov/. (2005). Inpatient hospital discharge query module for Utah counties and local health districts. Retrieved on January 4, 2005.

- Jeffcoat, M.K.; Geurs, N.C.; Reddy, M.S.; Cliver, S.P.; Goldenberg, R.L.; Hauth, J.C. (2001, July). Periodontal infection and preterm birth. Journal of the American Dental Association, Vol. 132, 875-880.

- Khader, Y.S.; Quteish, T. (2005, February). Periodontal diseases and the risk of preterm birth and low birth weight: A meta-analysis. Journal of Periodontology. Vol. 76(2), 161-165.

- Lopez, N.J.; Smith, P.C.; Gutierrez, J. (2002). Periodontal therapy may reduce the risk of preterm low birth weight in women with periodontal disease: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Periodontology, Vol. 73, No. 8, 911-924.

- Michalowicz, B.S; Hodges, J.S.; DeAngelis, A. J.; Lupo, V.R.; Novak, M.J.; Ferguson, J.E.; Buchanan, W.; Bofill, J.; Papanou, P.N.; Mitchell, D.A.; Matseoane, S.; Tschida, P.A. (2006). Treatment of periodontal disease and the risk of preterm birth. New England Journal of Medicine. Vol. 355, No. 18, 1885-1894.

- Moore, S.; Ide, M.; Coward, P.Y.; Randhawa, M.; Borkowska, E.; Baylis, R.; Wilson, R.F. (2004). A prospective study to investigate the relationship between periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcome. British Dental Journal, Vol. 197, No. 5, 251-258.

- Offenbacher, S.; Katz, V.; Fertik, G. (1996). Periodontal infection as a possible risk factor for preterm low birth weight. Journal of Periodontology, Vol. 67, 1103-1113.

- Vohr, B.R.; Wright, L.L.; Dusick, A.M. (2000). Neurodevelopmental and functional outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network, 1993-1994. Pediatrics. Vol. 105, 1216-1226.