Table of Contents

Abstract

Objectives: To examine gender-based violence (GBV) against sexual and gender minority (SGM) women at the University of Utah as structural violence. A better understanding of GBV within SGM populations can improve prevention efforts and intervention, and advance further research.

Methods: This study utilized quantitative methods of data collection in the form a survey.

Results: This pilot study found that among University of Utah women responding to the survey (N = 211), bisexual women (n = 53) reported experiencing GBV at disproportionately higher rates than their heterosexual counterparts (n = 116) in the past 12 months (n = 14 [27%], n = 17 [15%] respectively). The most highly reported type of GBV were unwelcome sexual advances, gestures, comments, or jokes (n = 35 [71%], n= 52 [47]), followed by being shown or sent explicit photos or videos (n = 15 [31%], n = 15 [13%]) among bisexual and heterosexual students, respectively.

Conclusions: SGM women are at greater risk of experiencing GBV, as they are subject to additional factors characteristic of their marginalization. These factors interact at individual, interpersonal, and structural levels, influencing key health outcomes among SGM women.

Health Implications: Approaching GBV against SGM women as an issue of structural violence can facilitate a more comprehensive understanding and enhance efforts to address gaps in existing services and resources. In doing so, the emotional, physical, and social wellbeing of these marginalized populations can be improved.

Introduction

Estimates indicate that 1 in 3 women worldwide will experience gender-based violence (GBV) in her lifetime.1 Among women attending college, 26 percent of undergraduate and 10 percent of graduate students are targets of sexual assault and/or rape.2 Heteronormativity is implicit in this statistic in the historically and current view that heterosexuality is assumptive for both agents and targets of GBV. GBV is “violence directed at an individual based on his or her biological sex or gender identity. It includes physical, sexual, verbal, emotional, and psychological abuse, threats, coercion, and economic or educational deprivation, whether occurring in public or private life.”3 Women are more likely targets for GBV than men. In support of the idea that GBV as currently constructed is heteronormative, emerging data suggest that sexual and gender minority (SGM) women (e.g., bisexual, transgender, lesbian women) are at greater risk of experiencing GBV compared to their heterosexual counterparts. Some research has indicated that SGM women overall are 3.7 times more likely than heterosexual women to experience GBV.4 Other research suggests that bisexual women are 1.8 to 2.6 times more likely to experience GBV than heterosexual women.5 SGM women are also more likely to be targets of GBV by both women and men agents.5 In this pilot mixed-methods study, we examined the incidence and experience of GBV for SGM women at the University of Utah (UU), the state’s flagship public institution.

Methods

This pilot project used quantitative data collection in the form of a survey open to university community members. The UU’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the project. Due to the pandemic, the university was largely operating remotely at this time. Because student life was disrupted during this phase of the study, data collection was negatively impacted. We present here a preliminary consideration of our findings.

Data Collection: Quantitative

The project began with the development of a quantitative data collection tool in REDCap, a research electronic data capture software, and took approximately 10 minutes to complete.6 The survey was composed of 52 questions based on the Draft Instrument for Measuring Campus Climate Related to Sexual Assault developed by the US Department of Justice7 as well as on Utah’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (UT-BRFSS).8 Survey questions included items assessing sexual violence, eg, “In the past 12 months, has anyone HAD SEX with you or ATTEMPTED to have sex with you after you said or showed that you didn’t want them to or without your consent? (yes/no),” and intimate partner violence, eg, “During the past 12 months did an intimate partner push, hit, slap, kick, choke, or physically hurt you in any other way? (yes/no).”

Once the survey was constructed, we recruited participants from the UU from September to December 2020. We announced the study in a regular newsletter for medical and health students, staff, and faculty. We also distributed the survey link to colleagues in our professional networks at the UU and posted flyers at several campus locations. The total number of survey respondents was 211.

Analysis

Descriptive and frequency data from the survey are included here to capture perceptions about GBV in a higher education setting from respondents who identify as women on a university campus.

Results

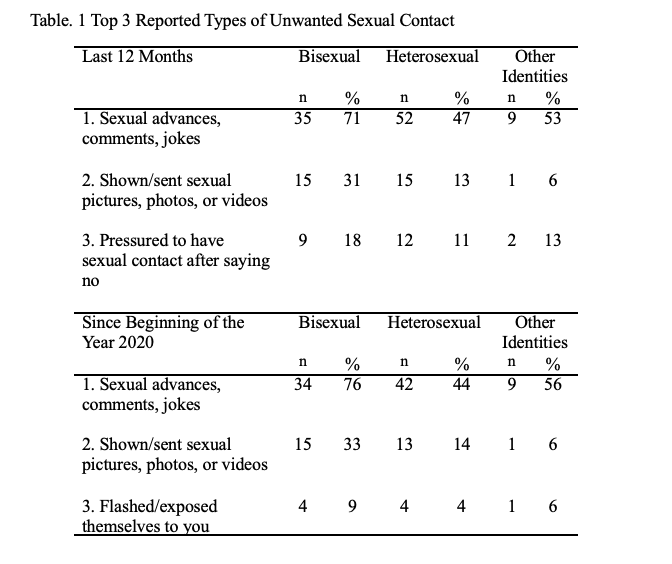

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for the top 3 reported types of GBV experienced by heterosexual and bisexual women in the last 12 months, with the start date falling between September and December 2019, depending on when the survey was completed in 2020. The top 3 reported types of unwanted sexual misconduct were (1) unwanted sexual advances, comments, and/or jokes, (2) shown/sent unwanted sexual pictures, photos, or videos, and (3) sexual contact after saying “no.” It is worth noting participants reported experiencing the same top 2 forms of GBV since the beginning of 2020. The third-most frequently reported type of GBV experienced since the beginning of 2020 was being “flashed or exposed themselves to you without your consent,” which was different than findings for the last 12 months.The change in the third-most reported type of unwanted sexual violence from being pressured to having sex to being flashed by others may give insight into how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted unwanted sexual contact.

Strengths & Limitations

The study is limited by its small sample size, for which there are several reasons. The study took place after the COVID-19 pandemic had begun, which made it difficult to recruit participants. The volatile topic of the study may also have contributed to lower participation. These factors possibly contributed to a sample size that was not as robust as planned.

Responses to the survey gave us preliminary information about how SGM women experience GBV in a university setting. This data provides useful information for future studies. Additionally, we now have a better idea of how to recruit participants for our next study to allow for a larger sampling. Further exploration might examine how the COVID-19 pandemic has contributed to sexual and gender minority women’s experiences of gender-based violence. Qualitative methods of data collection may also yield substantial insights into these experiences.

Discussion

Sample characteristics for the 211 participants who completed the survey are shown in Table 2. Only 19 percent identified as non-White, while just under 20 percent identified as non-female assigned at birth, with the same percentage identifying their gender identity as women. Due to the small number of participants identifying as gay/lesbian or pansexual (5%), our survey findings primarily provide insight into how heterosexual and bisexual White women experience GBV at the UU. Participants who identified as lesbian/gay, pansexual, or another sexual orientation not listed in our survey were combined into “other identities” in Table 2.

Although it is easier to identify GBV at the individual level, GBV is an example of structural violence. In the effort to promote health equity for SGM populations, it is crucial to explore GBV against SGM women within the context of structural violence. Structural violence is defined as a “form of violence wherein some social structure or social institution may harm people by preventing them from meeting their basic needs.”9 The Health Equity Promotion Model (HEPM) (see Figure 1)10 provides a useful framework for understanding how GBV structural and individual factors interact to influence key mental and physical health outcomes among SGM women.

Reflecting the existing literature,11 our findings suggest that rates of GBV among bisexual women in Utah are higher than in heterosexual, cisgender populations. While heterosexual and cisgender women face many of the same risk factors for experiencing GBV,SGM women are subject to additional factors characteristic of their marginalization, such as discrimination, identity concealment, and social stigma.10, 11 These stressors manifest and interact at structural levels, such as heterosexism, and individual and interpersonal levels, including targeting because of one’s non-heterosexual and/or non-cisgender identities. Such a cascade contributes to the greater likelihood that SGM women experience GBV and feel discouraged from seeking assistance.12

We typically examine GBV through a heteronormative perspective, depicting(heterosexual) men as perpetrators and (heterosexual) women as victims. Heteronormative assumptions about GBV are sustained at the structural level through institutional heterosexism.12Other structural elements manifest in the form of widespread social conditions and attitudes, such as stigma, exclusion, and erasure of SGM identities.12

Even if an individual knows cognitively that anyone can perpetrate or experience GBV regardless of their gender or sexual orientation, the occurrence of such can be difficult to identify if GBV is only recognized and validated in heterosexual, cisgender relationships. The lack of awareness regarding GBV against SGM populations is an ongoing, structural issue in terms of both the relevant literature and within the larger cultural consciousness. This results in GBV against SGM going both unnoticed and unaddressed, thereby further perpetuating the myth that it does not exist and simultaneously worsening its effects.

Positioning GBV against SGM women as an issue of structural violence invites opportunities for greater mobilization. Considering the various structural elements that contribute to GBV allows for exploration and acceptance of one’s personal responsibility for a societal issue. It also draws attention to shifting gender norms, the need for education about GBV in SGM populations, and the empowerment of girls and women across the lifespan.In this way, every person can take part in changing the environment to prevent GBV.

Health Implications

GBV manifests structurally via individual, social, and political attitudes and conditions.For example, legal definitions of GBV, discrimination from service providers, and a dearth ofLGBTQ+ specific resources result in fewer avenues for justice for SGM women.5 Current states’ legal definitions about domestic violence–a form of GBV–that exclude same-sex couples impede victim/survivor ability to pursue legal remedies.5 When GBV occurs in same-gender relationships and the individuals involved are of similar stature, police tend to assume equivalent power dynamics in the relationship, and all too often they arrest both parties, known as dual arrest.13 When the GBV incident involves physical violence, the dual arrest paradigm may preclude the actual target being able to access protections available through statute, while the GBV agent may use the dual arrest to attempt to convince theGBV target that they are also culpable for the violence. Such a dynamic may support and propagate a continuing cycle of GBV in SGM relationships.

One reason bisexual women may be at greater risk for GBV, and less likely to reach out subsequent to being targeted, is fear of disclosing their sexual orientation. Long-term concealment of sexual orientation has been linked to increased risk for depression and chronic health conditions.14 GBV is associated with a myriad of poor physical and mental health outcomes, including depression, post traumatic stress disorder, chronic illness, and sleep disorders.15, 16 This links to 2 of the 7 domains of health: mental and physical health.17 The intersection of these 2 dynamics (identity concealment, poorer mental and physical health) may in part explain the disparately high rates of GBV that bisexual women experience.The top 2 reported types of GBV experienced at the college level by both bisexual and heterosexual participants were unwelcome sexual advances, gestures, comments, or jokes, and receiving unwanted sexual pictures, photos, or videos. This finding indicates that bisexual and heterosexual women in college may experience similar, specific types of GBV, and it highlights an opportunity for universities to develop resources aimed at addressing them. It is critical to keep the ubiquity of the experience in mind when developing resources and support on university campuses, as repeated university-wide announcements about specific incidences of GBV can contribute to secondary trauma. While inadvertent, such messaging can act to perpetuate GBV at an institutional level.

It is also important to consider the lack of resources and avenues for justice for those who experience technological forms of GBV. This absence is significant, as technological forms ofGBV (such as the sharing of explicit photos without consent) can have severe, lasting consequences for the affected individual, especially SGM.18 The victim-survivor may suffer great impacts to their psychological and emotional wellbeing; such impacts may be compounded if assistance for GBV does not recognize or competently address violence enacted through digital means. Certain types of technological GBV have impeded the victim-survivor’s ability to maintain employment, thereby affecting their financial health and stability.11

Continued research is necessary to gain a better understanding of GBV against SGM women as an issue of structural violence. Identifying other structural elements contributing to GBV can enhance efforts to address gaps in existing services and provide more comprehensive, competent resources for SGM populations.

References

1. Gender and women’s mental health. World Health Organization. Accessed April 16, 2016. http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/genderwomen/en/

2. Campus sexual violence: Statistics. RAINN. Accessed September 30, 2021. https://www.rainn.org/statistics/campus-sexual-violence

3. CDC training helps healthcare providers respond to gender-based violence. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated November 19, 2020. Accessed October 4, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/stories/2020/cdc-training-helps-healthcare-providers.html

4. Flores AR, Langton L, Meyer IH, Romero AP. Victimization rates and traits of sexual and gender minorities in the United States: Results from the National Crime Victimization Survey 2017. Science Advances. 2020;6(40):1-10. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aba6910.

5. Brown TNT, Herman JL. Intimate partner violence and sexual abuse among LGBT people: A review of existing research. 2015. Accessed September 30, 2021. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Intimate-Partner-Violence-and-Sexual-Abuse-among-LGBT-People.pdf

6. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2009;42(2):377-381.

7. Draft Instrument for Measuring Campus Climate Related to Sexual Assault. U.S. Department of Justice’s Office on Violence against Women. 2016. Accessed 2019. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/RevisedInstrumentModules_1_21_16_cleanCombined_psg.pdf

8. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Questionnaire. Utah Department of Health, Office of Public Health Assessment. 2016. Accessed 2019. https://opha.health.utah.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/2016-Utah-BRFSS.pdf

9. Sinha P, Gupta U, Singh J, Srivastava A. Structural violence on women: An impediment to women empowerment. Indian Journal of Community Medicine. 2017;42(3):134.

10. Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Simoni JM, Kim H-J, et al. The health equity promotion model: Reconceptualization of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health disparities. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2014;84(6):653–683. doi:10.1037/ort0000030.

11. Edwards KM, Sylaska KM, Neal AM. Intimate partner violence among sexual minority populations: A critical review of the literature and agenda for future research. Psychology of Violence. 2015;5(2):112-121. doi:10.1037/a0038656

12. Scheer JR, Martin-Storey A, Baams L. Help-seeking barriers among sexual and gender minority individuals who experience intimate partner violence victimization. In: Russell B, ed. Intimate Partner Violence and the LGBT+ Community: Understanding Power Dynamics. Springer; 2020:139-158.

13. Masri A. Equal rights, unequal protection: Institutional failures in protecting and advocating for victims of same-sex domestic violence in post-marriage equality era. Tulane Journal of Law & Sexuality. 2018;27:75-90.

14. Hoy-Ellis CP, Fredriksen-Goldsen KI. Lesbian, gay, & bisexual older adults: Linking internal minority stressors, chronic health conditions, and depression. Aging and Mental Health. 2 Apr 2016:1-10. doi:10.1080/13607863.2016.1168362

15. Lutwak N. The psychology of health and illness: The mental health and physiological effects of intimate partner violence on women. The Journal of Psychology. 2018;152(6):373-387.298. doi:10.1080/00223980.2018.1447435

16. Dillon G, Hussain R, Loxton D, Rahman S. Mental and physical health and intimate partner violence against women: A review of the literature. International Journal of Family Medicine. 2013;2013:1-10. doi:10.1155/2013/313909

17. Frost C, Murphy P, Shaw J, et al. Reframing the view of women’s health in the United States: Ideas from a multidisciplinary National Center of Excellence in Women’s Health Demonstration Project. Clinics in Mother and Child Health. 2013;11(1):1-3. 305 doi:10.4172/2090-7214.1000156

18. Powell A, Henry N, Flynn A. Image-based sexual abuse: An international study of victims and perpetrators. Summary report. 2018:1-17. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.35166.59209

Citation

Powell DK, Younce B, Gren LH, Hoy-Ellis CP, & Frost CJ. (2022). Gender-Based Violence as Structural Violence Among Sexual & Gender Minority Populations: Pilot Data from the University of Utah. Utah Women’s Health Review. doi: 10.26054/0d-nym1-7vr1