Table of Contents

Background

Arthritis includes over 100 different rheumatic diseases (Hardin, Crow, & Diamond, 2012). Although the causes and symptoms vary, they all share symptoms of pain, swelling, stiffness, and tenderness in one or more joints (Hardin et al., 2012). Arthritis may lead to decreased mobility, and over time joints may lose their normal shape (Hardin et al., 2012). Osteoarthritis (OA), the most common form of arthritis, is a degenerative joint disease (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017c). OA develops over a long time and is the result of long-term wear, tear, and break-down of joint cartilage (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017c). Rheumatoid arthritis (RA), the second most common form of arthritis, is an auto-immune disease that attacks joints and can affect multiple systems, tissues, and organs throughout the body (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017e). Lupus, fibromyalgia, and gout are other common forms of arthritis (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017b).

Arthritis is the most common cause of disability in the US (Utah Department of Health, 2015b). In 2017, the prevalence of arthritis among adults ages 18 and older in Utah was 19.3% (Utah Department of Health, 2015b). This represents approximately 419, 800 individuals based on the estimated Utah population 18 years and older for 2017 (Utah Department of Health, 2015c). Women are significantly more likely to suffer from arthritis than men, according to the Utah Department of Health (UDOH): 26% of adult women in Utah versus 19% of men had arthritis (Utah Department of Health, 2015b). Women are also more likely to have lupus, which is a type of arthritis with distinct differences (Hardin et al., 2012). New cases of RA are about two to three times higher in women than in men (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017e), and women of childbearing years (15-44 years) are the most likely to develop lupus (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017d).

Biology, genetics, hormones and environmental factors all contribute to these differences (Hardin et al., 2012). For example, women are two to five times more likely than men to sustain an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury, a risk factor for developing knee OA ; this may be due to differences in the shape of their knee bones (Hardin et al., 2012). Specific genes are also associated with a higher risk of certain types of arthritis (Hardin et al., 2012). Other risk factors include obesity, smoking, joint injuries, infection, and occupations that involve repetitive knee bending and squatting (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017e; Hardin et al., 2012).

The effects of arthritis are wide-ranging. Arthritis is a leading cause of disability and a major cause of severe joint pain (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017a). In Utah, over half (56.2%) of adults with arthritis are taking prescribed pain medications, which is significantly greater than those without arthritis (25.8%) (Utah Department of Health, 2015b). Many types of arthritis, especially RA, are “associated with an increased risk of heart disease and even early death” (Hardin et al., 2012). In Utah, 53% of adults with heart disease and 47% of adults with diabetes also have arthritis (Utah Department of Health, 2015b). Arthritis limits many of their normal activities making it harder to manage their heart disease, diabetes, or other chronic conditions (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017a).

Adults with arthritis are also more likely to report an injury related to a fall, have substantial activity limitation, work disability, and reduced quality of life (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017a). Women tend to experience many of the negative effects of arthritis to a greater degree than men. Women have greater pain, greater reductions in knee function, and greater reductions in their overall quality of life than men (Hardin et al., 2012).

Data

Data

The prevalence of arthritis in Utah consistently stayed around 21% from 2011-2015 with the prevalence staying around 24% for women and 18% for men (see Figure 1). In 2014, 24.1% of U.S. adults had arthritis (Division of Behavioral Science, CDC Office of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services, 2015). This is significantly higher than the 2014 prevalence in Utah of 21.4% (Utah Department of Health, 2014).

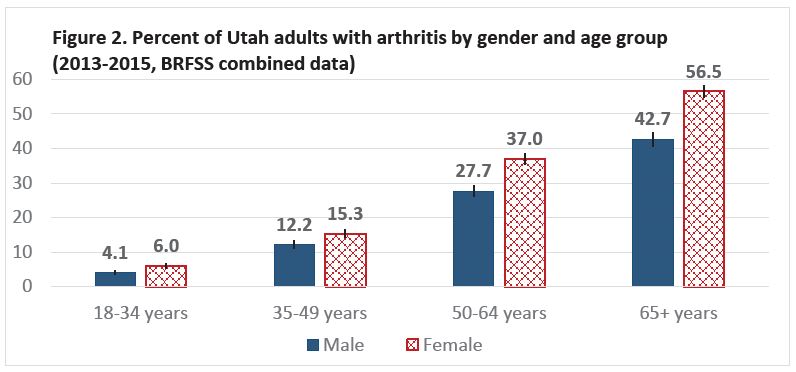

Arthritis is increasingly more common as people age, although people of all ages can be affected by the disease. In Utah, 85% of people with arthritis in 2015 were younger than 65 (Utah Department of Health, 2015b). Arthritis is significantly more common for women than men in every age group (Utah Department of Health, 2015a) (see Figure 2).

Figure three shows additional differences by sex and arthritis status. Women with arthritis are more likely than men with arthritis to have been diagnosed with depressive disorder, report 7 days or more of poor mental health within the past 30 days (Utah Department of Health, 2015b), and to report that they were limited in any of their usual activities due to their arthritis (Utah Department of Health, 2015a). Even though women, regardless of arthritis status, are more likely than men to report more poor mental health and to be diagnosed with depressive disorder, women with arthritis are also significantly more likely than women without arthritis to report these conditions (see Figure 3). The exact reasons for the difference in mental health between men and women are not known as they arise from complex interactions of genetics, environmental factors, and psychology. However, it is apparent that women with arthritis have a higher burden of poor mental health and activity limitations than men with or without arthritis, and than women without arthritis.

Impact on Other Domains of Health

Arthritis also impacts social and occupational domains of health. Arthritis lessens the ability of affected individuals to participate in social activities such as shopping, going to the movies, or going to religious or social gatherings. Again, women are more likely to report social participation restriction than men due to their arthritis (18% of women, 13% of men) (Utah Department of Health, 2015b). Limitations in ability to work or to do certain types of work are also reported by 34% of working-age women and 32% of working-age men due to their arthritis (Utah Department of Health, 2015b). The physical, social, and work limitations experienced by people with arthritis likely contribute to their reduced quality of life and greater number of days with poor mental health.

Current Efforts, Resources, and Recommendations

According to the CDC, “physical activity can decrease pain and improve physical function by about 40%” and may reduce annual healthcare costs by approximately $1,000 per person, yet one in three adults with arthritis are physically inactive (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017a). Adults with arthritis can also reduce their symptoms by participating in a disease self-management education program (SMEP) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017a).

While over half of adults with arthritis are using prescribed pain medications (56.2%), only 16.6% have ever attended a SMEP (Utah Department of Health, 2015b). The Utah Arthritis Program (UAP) works with organizations statewide to offer evidence-based SMEPs and exercise programs, such as EnhanceFitness and the Arthritis Foundation Exercise Program (AFEP), for people with arthritis. Living Well with Chronic Conditions, Utah’s main SMEP for people with arthritis, helps participants learn about and improve their use of medications, exercise and nutrition, communication with providers and loved ones, and symptom management (Lorig et al., 2001). The class mitigates the negative effects of arthritis. Participants report significant improvements in general health, fatigue, disability, and social activity limitations (Lorig et al., 2001).

“Adults with arthritis are significantly more likely to attend an education program when recommended by a provider” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017a). The Utah Arthritis Program developed a referral website (https://arthritis. health.utah.gov/) for people with chronic conditions, including arthritis, to find self-management and exercise programs near them or for physicians to register patients directly into a workshop. Current classes and schedules can be found at livingwell.utah.gov.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017a). Arthritis in America: Time to Take Action! CDC Vital Signs, Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/pdf/2017-03-vitalsigns.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017b). Arthritis Types. Retrieved May 30, 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/basics/types.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017c). CDC Osteoarthritis Fact Sheet. Retrieved May 30, 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/basics/osteoarthritis.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017d). Lupus Detailed Fact Sheet.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017e). Rheumatoid Arthritis Fact Sheet. Retrieved May 30, 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/basics/rheumatoid-arthritis.html

- Division of Behavioral Science, CDC Office of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services, C. for D. C. and P. (2015). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). Office of Public Health Assessment.

- Hardin, J., Crow, M. K., & Diamond, B. (2012). Get the facts: Women and Arthritis. Arthritis Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.arthritis.org/New-York/-Files/Documents/Spotlight-on-Research/Get-the-Facts-Women-and-Arthritis.pdf

- Lorig, K. R., Ritter, P., Stewart, A. L., Sobel, D. S., Brown, B. W., Bandura, A., … Holman, H. R. (2001). Chronicdisease self-management program: 2-year health status and health care utilization outcomes. Medical Care, 39(11), 1217–23. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11606875

- Utah Department of Health. (2014). Behavioral Risk Factor Surevillance Systems (BRFSS), 2014. Salt Lake City: Office of Public Health Assessment. https://ibis.health.utah.gov/.

- Utah Department of Health. (2015b). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), 2015. Salt Lake City: Utah Department of Health, Center for Health Data. https://ibis.health.utah.gov/.

- Utah Department of Health. (2015c). IBIS-PH, Dataset Queries, Population Estimates for 2015. Salt Lake City: https://ibis.health.utah.gov/.

Citation

George S. (2019). Arthritis in Utah: Significant Differences for Women. Utah Women’s Health Review. doi: 10.26054/0K7E21H4QA.