Table of Contents

Background

Social cohesion is a fundamental social determinant of health that signifies the strength and quality of relationships among individuals or groups within a given community or society.1-3 It is also an important component of social health as outlined by the 7 Domains of Health, which reflects an individual’s “connection to family, intimate partner, friends, co-workers, and larger structures such as community, church, and workplace.”4 Numerous studies underscore the significance of social cohesion in promoting better mental and physical health, reducing risky behaviors, preventing disease, ensuring access to healthcare, fostering resiliency, promoting health equity, and improving the overall quality of life.5 Additionally, people are more likely to engage in community life, contribute to collective well-being, and experience positive health outcomes when they perceive strong social cohesion within their community.3,5

Social cohesion plays a pivotal role in shaping the overall well-being and health outcomes of individuals and communities, particularly for young people. Mental health is intricately linked to physical health, and maintaining a healthy mental state can mitigate behavioral risks such as substance use, unintended pregnancy, sexually transmitted diseases, and violence, while also reducing rates of self-harm, truancy, and feelings of isolation.6,7 Positive habits developed during adolescence tend to persist into adulthood, reinforcing the importance of fostering strong social cohesion during youth to cultivate lifelong positive health outcomes.

Various approaches can be employed to enhance social cohesion and foster a sense of connectedness, trust, and mutual support within a community.8 These include community engagement and participation, promoting inclusivity, building social networks, supporting social initiatives, investing in public spaces, and celebrating cultural diversity.8 Art and music therapy show promise in improving mental health conditions and social wellbeing.9,10 In particular, participating in a music group cultivates characteristics that strengthen social cohesion.11 Group members share common purposes and goals, create social bonds during rehearsals and performances, rely on effective communication to synchronize their efforts, engage in community outreach activities, and contribute to a sense of continuity and tradition. Research indicates that participating in a music group can expedite the development of strong social cohesion compared to other forms of social interaction.12,13 This holds particular significance for young people, who are in the process of developing their social identities and shaping their worldviews.

Data Snapshot

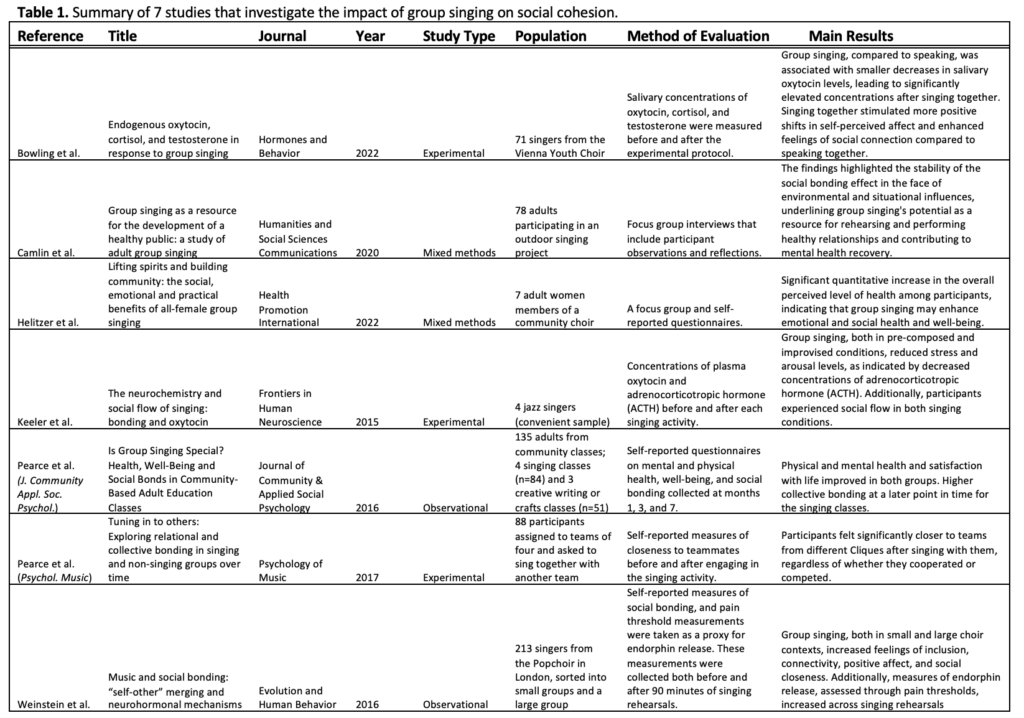

Given the recognized potential of music groups in fostering social cohesion, a review was undertaken to explore the relationship between group singing and social cohesion. A search of the scientific literature was conducted across multiple electronic databases, including PubMed, PsychINFO, Scopus, and CINAHL, from January to February 2024. Search terms included combinations of social bonding, group singing, social cohesion, choir, chorale, social network, community, and social capital. Articles meeting the following criteria were included in the results: publication date from 2014 to present, written in English, focus on group singing and/or choir participation, measurement of ‘social cohesion’ and/or ‘social bonding’ as a primary or secondary outcome, inclusion of original research studies with scientifically robust study designs, and exclusion of participants with significant mental or physical health conditions. The search yielded a total of 86 articles, from which seven met the predefined inclusion criteria (Table 1).

All seven studies included in the review demonstrated a positive correlation between group singing and strengthened social cohesion (Table 1). While all studies demonstrated a positive association between group singing and social cohesion, it is important to note the variations in methodologies, populations, and measures used across studies, which may influence the interpretation of the findings.

Bowling et al measured salivary oxytocin levels (a hormone associated with social bonding and trust) in the Vienna Youth Choir before and after singing as a group and singing alone, as well as before and after speaking as a group and speaking alone.14 Both activities resulted in a decrease in salivary oxytocin; however, singing as a group was associated with a significantly smaller decrease in oxytocin compared to speaking as a group, indicating that group singing may contribute to stronger feelings of social connectedness than group speaking.14 Keeler et al examined plasma oxytocin and adrenocorticotropic hormone (a hormone released in response to stress) levels in jazz singers, reporting reduced stress hormones and increased feelings of connectedness during group singing, although the small sample size (n=4) may limit generalizability.15 In a study of singers from the London Popchoir, Weinstein et al. used self-reported measures of social bonding and pain threshold measurements to conclude that group singing increases feelings of inclusion, connectivity, positivity, and social closeness and may be associated with an increase in endorphin release.16

Pearce et al (J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol.) followed four community-based singing classes and three non-singing (creative writing and craft) classes over the span of seven months; although physical and mental health and satisfaction of life did not differ between the singing and non-singing groups, group singing may be associated with quicker feelings of social bonding.12 In another study (Pearce et al, Psychol. Music), participants were randomly assigned to teams of four and asked to sing together.17 Self-reported measures of closeness to teammates before and after the singing activity were collected, and participants reported increased feelings of closeness to less-familiar groupmates after singing together.17 Camlin et al conducted focus group interviews of adults participating in an outdoor singing project, and their findings confirm the social bonding effects strengthened by group singing.18 Lastly, Helitzer et al utilized focus group interviews and a questionnaire to assess the social connectedness of an all-female choir, revealing a significant qualitative increase in the overall perceived level of health among participants and indicating that group singing may enhance emotional and social health and well-being.19

Recommendations

Limited research has been conducted quantifying the extent of social cohesion that results from group singing. The studies highlighted in this paper either measure an increase in social cohesion qualitatively or consider it as a secondary outcome alongside related factors, rather than as the primary measure. Furthermore, there is a notable gap in the literature concerning studies that are focused on middle- or high-school-aged participants. Given the ongoing decline in funding for public school arts programs nationwide, coupled with Utah’s overall low expenditure on education,20-23 it becomes imperative to study the impact of school choral and music programs on social cohesion and other factors contributing to youth mental wellbeing.

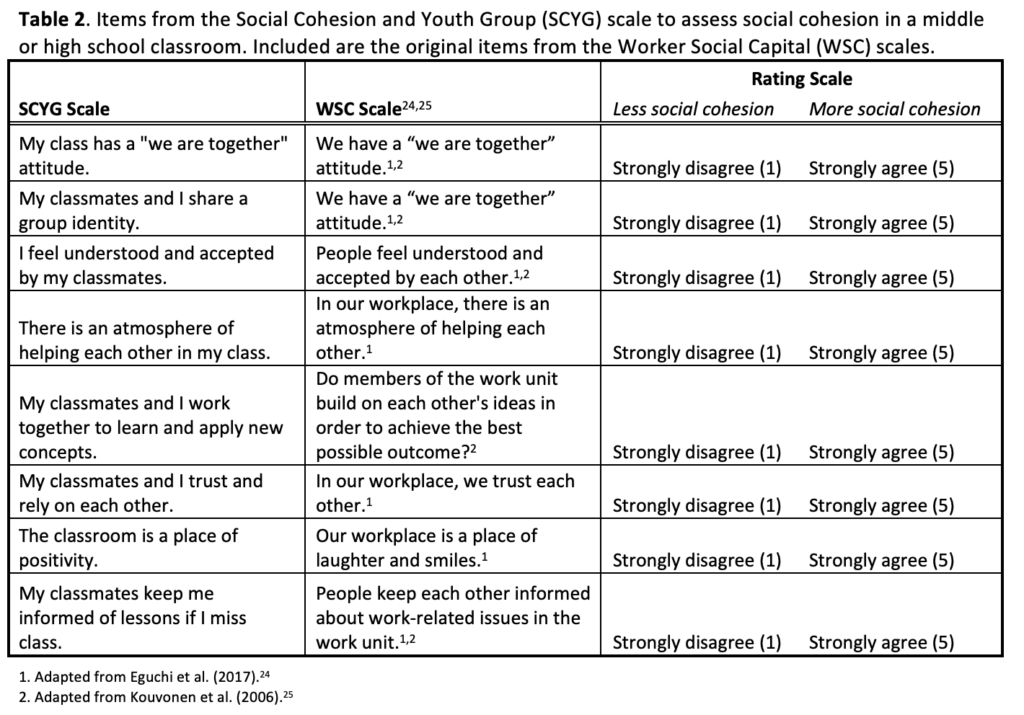

To address these gaps, it is proposed that the Workplace Social Capital (WSC) scale be adapted to quantify the association between group singing and social cohesion.24,25 Initially introduced by Kouvonen et al. in 200625 and subsequently refined by Eguchi, Tsutsumi, Inoue, and Odagiri in 2017,24 the WSC scale evaluates social capital (defined as “ those features of social relationships that facilitate collective action for mutual benefit”25) and its relation to physical and mental health outcomes. Because the WSC scale is intended to measure social capital among working adults, much of its verbiage does not directly apply to adolescents in a school setting. However, by modifying the scale to be more student-centric, the adapted scale, termed the Social Cohesion Youth Group (SCYG) scale, can effectively gauge the impact of group singing on the social cohesion of adolescents in Utah. Table 2 introduces the proposed SCYG scale alongside the WSC from which it was adapted. The SCYG scale comprises eight questions, each assessed on a Likert scale ranging from 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree. Higher scores denote stronger perceptions of social cohesion.

Conclusion

Social cohesion is a crucial social determinant of health and an important component of the 7 Domains of Health, reflecting the interconnectedness, relational quality, and social bonds within communities. Its impact spans various domains, including mental and physical well-being, risk reduction, healthcare access, resilience, equity, and overall quality of life, and it is associated with better mental and physical health, reduced risky behaviors, disease prevention, access to healthcare, resiliency, health equity, and overall quality of life. While existing research underscores the efficacy of art therapy and group singing in strengthening social cohesion, limited attention has been directed towards the efficacy of school choral and music programs in cultivating socially adept and physically and mentally healthy youth. To address this gap, the implementation of the Social Cohesion Youth Group (SCYG) scale, adapted to middle- or high-school students from the Worker Social Capital scale, is a promising method for quantifying the impact of group singing on strengthening social cohesion among adolescents, ultimately demonstrating the importance of the continued funding of school music programs.

References

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Social Cohesion. Accessed March 11, 2024, https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health/literature-summaries/social-cohesion

2. Fancourt D, Finn S. What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being? A scoping review. 2019. Health Evidence Network (HEN synthesis report 67).

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How Does Social Connectedness Affect Health? Accessed March 11, 2024, https://www.cdc.gov/emotional-wellbeing/social-connectedness/affect-health.htm

4. Frost CJ, Murphy PA, Shaw JM, et al. Reframing the view of women’s health in the United States: Ideas from a multidisciplinary National Center of Excellence in Women’s Health Domenstration Project. JMCH. 2013;11(1)doi:10.4172/2090-7214.1000156

5. Oberndorfer M, Dorner TE, Leyland AH, et al. The challenges of measuring social cohesion in public health research: A systematic review and ecometric meta-analysis. SSM – Population Health. 2022;17doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2022.101028

6. Ohrnberger J, Fichera E, Sutton M. The relationship between physical and mental health: A mediation analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2017;195:42-49. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.11.008

7. Feiss R, Pangelinan MM. Relationships between Physical and Mental Health in Adolescents from Low-Income, Rural Communities: Univariate and Multivariate Analyses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021-02-03 2021;18(4):1372. doi:10.3390/ijerph18041372

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ways to Improve Social Connectedness. Accessed March 11, 2024, https://www.cdc.gov/emotional-wellbeing/social-connectedness/ways-to-improve.htm

9. Jay EK, Moxham L, Patterson C. Using an arts‐based approach to explore the building of social capital at a therapeutic recreation camp. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2021-08-01 2021;30(4):1001-1009. doi:10.1111/inm.12856

10. Wang S, Agius M. The use of music therapy in the treatment of mental illness and enhancement of societal wellbeing. Psychiatr Danub. 2018;30:S595-S600.

11. Pesata V, Colverson A, Sonke J, et al. Engaging the Arts for Wellbeing in the United States of America: A Scoping Review. Frontiers in Psychology. 2022-02-09 2022;12doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.791773

12. Pearce E, Launay J, Machin A, Dunbar RIM. Is Group Singing Special? Health, Well‐Being and Social Bonds in Community‐Based Adult Education Classes. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology. 2016-11-01 2016;26(6):518-533. doi:10.1002/casp.2278

13. Pearce E, Launay J, Dunbar RIM. The ice-breaker effect: singing mediates fast social bonding. Royal Society Open Science. 2015-10-01 2015;2(10):150221. doi:10.1098/rsos.150221

14. Bowling DL, Gahr J, Ancochea PG, et al. Endogenous oxytocin, cortisol, and testosterone in response to group singing. Hormones and Behavior. 2022;139doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2021.105105

15. Keeler JR, Roth EA, Neuser BL, Spitsbergen JM, Waters DJM, Vianney J-M. The neurochemistry and social flow of singing: bonding and oxytocin. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2015-09-23 2015;9doi:10.3389/fnhum.2015.00518

16. Weinstein D, Launay J, Pearce E, Dunbar RIM, Stewart L. Singing and social bonding: changes in connectivity and pain threshold as a function of group size. Evolution and Human Behavior. 2016-03-01 2016;37(2):152-158. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2015.10.002

17. Pearce E, Launay J, Van Duijn M, Rotkirch A, David-Barrett T, Dunbar RIM. Singing together or apart: The effect of competitive and cooperative singing on social bonding within and between sub-groups of a university Fraternity. Psychology of Music. 2016-11-01 2016;44(6):1255-1273. doi:10.1177/0305735616636208

18. Camlin DA, Daffern H, Zeserson K. Group singing as a resource for the development of a healthy public: a study of adult group singing. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. 2020-08-05 2020;7(1)doi:10.1057/s41599-020-00549-0

19. Helitzer E, Moss H, O’Donoghue J. Lifting spirits and building community: the social, emotional and practical benefits of all-female group singing. Health Promot Int. 2022;37(6):daac112. doi:doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daac112

20. Nestbitt C. Utah has no plans to change lowest-in-nation education spending, officials say. The Salt Lake Tribune. January 8, 2024. https://www.sltrib.com/news/education/2024/01/08/utah-not-race-outspend-other/

21. American University School of Education. School Funding Issues: How Decreasing Budgets Are Impacting Student Learning and Achievement. Accessed March 11, 2024, https://soeonline.american.edu/blog/school-funding-issues/

22. Morrison N. How the Arts Are Being Squeezed Out of Schools. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/nickmorrison/2019/04/09/how-the-arts-are-being-squeezed-out-of-schools/?sh=47095520aaf4

23. Wood B. Utah school board gets earful after dropping middle school arts and health requirements. The Salt Lake Tribune. September 20, 2017. https://www.sltrib.com/news/education/2017/09/21/utah-school-board-gets-earful-after-dropping-middle-school-arts-and-health-requirements/

24. Eguchi H, Tsutsumi A, Inoue A, Odagiri Y. Psychometric assessment of a scale to measure bonding workplace social capital. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0179461. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0179461

25. Kouvonen A, Kivimäki M, Vahtera J, et al. Psychometric evaluation of a short measure of social capital at work. BMC Public Health. 2006-12-01 2006;6(1)doi:10.1186/1471-2458-6-251

Citation

Crouch S. (2024). A Review of Group Singing and Social Cohesion: Recommendations for Assessing Social Cohesion in Utah’s Youth. Utah Women’s Health Review. doi: 10.26054/d-wzh2-g09f