Table of Contents

Background

Utah has a notably high rate of sexual and domestic violence: 32% vs 29% nationally [5]. Female and male adults are not the only victims of this behavior. Adolescents exposed to domestic and sexual violence are at increased risk of acting aggressively towards their peers in the form of bullying and harassment [2]. These adolescents and all adolescents exposed to bullying in any capacity experience greater rates of suicidal ideation and behavior [1]. To improve adolescent health, it is imperative that the complex interplay between these three types of violence are further explored and prevention efforts are developed in order to break this cycle and optimize youth health and resiliency.

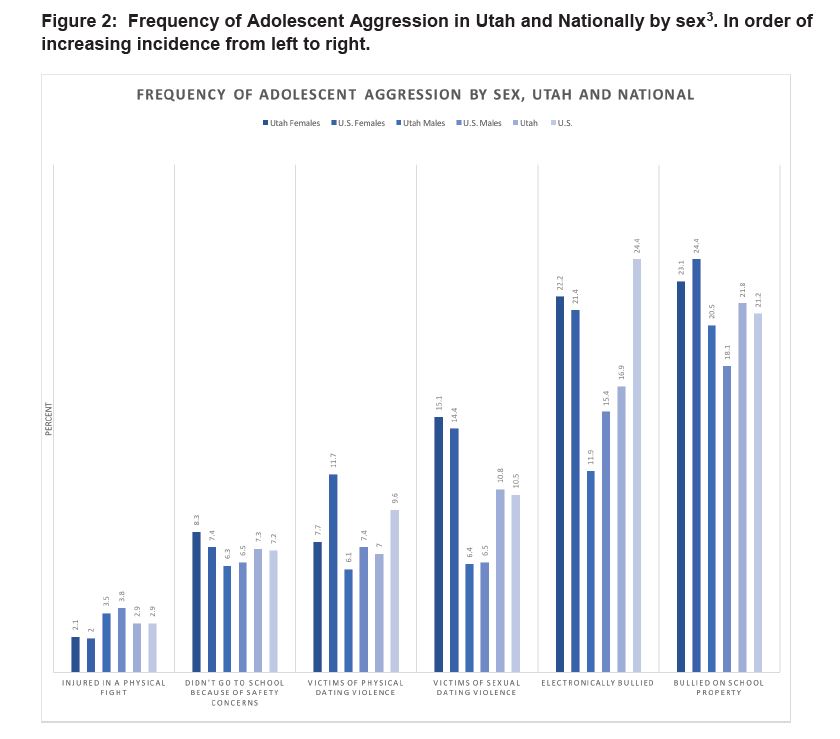

This data snapshot will explore population data and propose some approaches to build youth resilience and improve health outcomes for adolescents. Adolescents who are exposed to domestic violence are at increased risk of perpetrating aggressive behaviors in the form of fighting, dating violence, and bullying [2, 8]. Typically, they are more accepting of aggressive behaviors, experience higher rates of adolescent depression and more feelings of anger, and tend to demonstrate impaired regulation of anger [1]. Students exposed to domestic violence have poorer conflict management skills and poorer emotional regulation than those not exposed [2]. A 2014 meta-analysis found that involvement in bullying in any capacity (whether as a victim or perpetrator) is associated with suicidal ideation and behavior [1]. Notably, a 2006 Utah study found that adult victims of domestic violence are considerably more likely than non-victims to have witnessed domestic violence as a child (34%) or to have been abused by their parents (36 %) [3]. Utah ranks 7th in the nation for suicide among 10 to 17-year-olds (Figure 1) and has some of the higher aggression rates in the country (Figure 2). Those who are exposed to domestic violence are at higher risk for perpetrating adolescent aggression, having suicidal ideations, and committing suicide [1, 2].

The high rates of suicide, adolescent aggression, and adolescent suicide are especially noteworthy because bullying, assault, and suicide ideations are under-reported problems. Data on individuals who attempt suicide are limited. Such problems disproportionately affect minorities and low socioeconomic populations. For example, Hispanic female adolescents experience sexual dating violence at 16.0 percent, compared to 14.6 percent among white adolescent females [3], LGBTQ teens have a suicide rate between 1.5 and 3 times higher than heterosexual teens [12], and low-income areas such as South Salt Lake have remarkably poorer mental health overall. Because of the overlapping nature of these three phenomena, this research snapshot focuses on three key areas:

Because of the overlapping nature of these three phenomena, this research snapshot focuses on three key areas:

1) The impacts of domestic violence on aggression in adolescents.

2) The correlation between bullying and aggression on youth suicide rates.

3) The high rate of suicide in Utah, notably in adolescents.

Data

Self-reported Utah data from the 2013 Youth Risk Behavior Survey indicate that 7% of Utah students have been a victim of physical dating violence, 22% have been bullied on school property, and 11% percent have been victims of sexual dating violence [3]. Among children who have been exposed to domestic violence, nationally, 9% reported perpetrating physical violence, 44% reported bullying others during the current school term, and 16% reported having sexually harassed a peer in the last school year [2]. These high rates are especially salient in small areas within key populations, like South Salt Lake where the poverty rate is 28.5%, and 26% of children were victims of abuse [6].

Adolescent deaths from suicide are more prevalent among males, although attempts are far more evenly distributed, with females having significantly higher rates of hospitalization than males across age groups [11]. Overall, on mental health, Utah ranks 40th in the nation, having a high prevalence of mental illness and low rates of access to care [10]. In Utah, the rates of adolescent aggression are higher, if only slightly, than the national average. It stands to reason that the three phenomena are linked, especially in light of their strong correlation with socioeconomic status and education.

Available Resources and Conclusion

Suicide, domestic violence, and bullying are complex public health issues where discussion may be stigmatized and the victims may be blamed. As such, these topics are not openly discussed, making it difficult to collect valid data and potentially difficult to establish meaningful prevention measures. One approach to this complex web is to expand evidence-based violence prevention work offered to children and youth who are known to have been exposed to domestic violence. A second approach is to implement bystander prevention strategies that empower peers to intervene in the moment where they see situations brewing.

Programs that provide teachers and other adults who work with youth with skills to intervene in bullying/harassment, to be a safe, nurturing person to talk with, and to create safer spaces for learning is known to improve safety for LBGTQ youth, youth who have had adverse childhood experiences including exposure to domestic violence. The literature suggests that programs that target nearly all forms of adolescent aggression at their core can be created, using a social – emotional approach to teach communication skills, decision making, and the qualities of healthy and unhealthy relationships [2, 7].

Late adolescents living in poverty are almost twice as likely to have suicidal inclinations [9]. Because of the drastically higher rates of violence in areas like South Salt Lake, more research needs to be done in order to determine if this is a statewide problem, or one that is disproportionately affecting low-in-come families in areas like South Salt Lake. Further research can aid efforts to ameliorate the effects of exposure to domestic violence. Because exposure to domestic violence is linked to suicide, bullying, and other adverse behaviors, we need to continue to support youth who have been exposed and work to target aggressive behaviors across Utah.

References

- Holt, M. K., Vivolo-Kantor, A. M., Polanin, J. R., Holland, K. M., DeGue, S., Matjasko, J. L., Wolfe, M.. Reid, G. (2015). Bullying and Suicidal Ideation and Behaviors: A Meta-Analysis. Pediatrics,135(2), e496-509. Retrieved May 2, 2019, from http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/early/2015/01/01/peds.2014-1864

- Foshee, V. A., McNaughton Reyes, H. L., Chen, M. S., Ennett, S. T., Basile, K. C., DeGue, S., Vivolo-Kantor, A.M., Moracco, K.E., Bowling, J. M. (2016). Shared Risk Factors for the Perpetration of Physical Dating Violence, Bullying, and Sexual Harassment Among Adolescents Exposed to Domestic Violence. Journal of Youth and Adoles-cence,45(4), 672-686. doi:10.1007/s10964-015-0404-z

- Kann, L., et al. (2014, June 13). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance — United States, 2013. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved May 2, 2019 from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/ss/ss6304.pdf

- Madsen, S. R., Turley, T., & Scribner, R. T. (2017, February 6). Domestic Violence Among Utah Women [PDF]. Utah Women & Leadership Project.

- Black, M.C., Basile, K.C., Breiding, M.J., Smith, S.G., Walters, M.L., Merrick, M.T., Chen, J., & Stevens, M.R. (2011). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Summary Report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Why Health Matters for Intergenerational Poverty [Pamphlet]. (2013). Salt Lake City , Utah: Utah Department of Health.

- Suicide Among Teens and Young Adults. (n.d.). Retrieved May 2, 2019, from http://health.utah.gov/vipp/teens/youth-suicide/

- Baldry, A. C. (2003). Bullying in schools and exposure to domestic violence. Child Abuse & Neglect,27(7), 713- doi:10.1016/s0145-2134(03)00114-5

- Dupéré, V., Leventhal, T., & Lacourse, É. (2008). Neighborhood poverty and suicidal thoughts and attempts in late adolescence. Psychological Medicine,39(8), 1295-1306. doi:10.1017/s003329170800456x

- 2017 State of Mental Health in America – Ranking the States. Retrieved May 2, 2019, from http://www.mental-healthamerica.net/issues/2016-state-mental-health-america-ranking-states

- Thomas, D., LCSW. Utah Suicide Prevention Plan 2017-2021. Utah Division of Substance Abuse and Mental Health, Utah Suicide Prevention Coalition. Retrieved May 2, 2019, from https://health.utah.gov/vipp/pdf/Suicide/Sui-cidePreventionCoalitionPlan2017-2021.pdf

- Suicide Prevention Resource Center. (2008). Suicide risk and prevention for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and trans-gender youth. Newton, MA: Education Development Center, Inc. retrieved May 2, 2019 from https://www.sprc.org/sites/default/files/migrate/library/SPRC_LGBT_Youth.pdf

Citation

Diener Z & Sheinberg A. (2019). A Complex Web: Exposure to Domestic Violence, Aggressive Behaviors and Suicidality in Utah Adolescents. Utah Women’s Health Review. doi: 10.26054/0KFTYRFGC2.